Updated Sept. 26: Additional photos and interviews with a board member, EQUITY Education, parents, teachers, and students were added to this story.

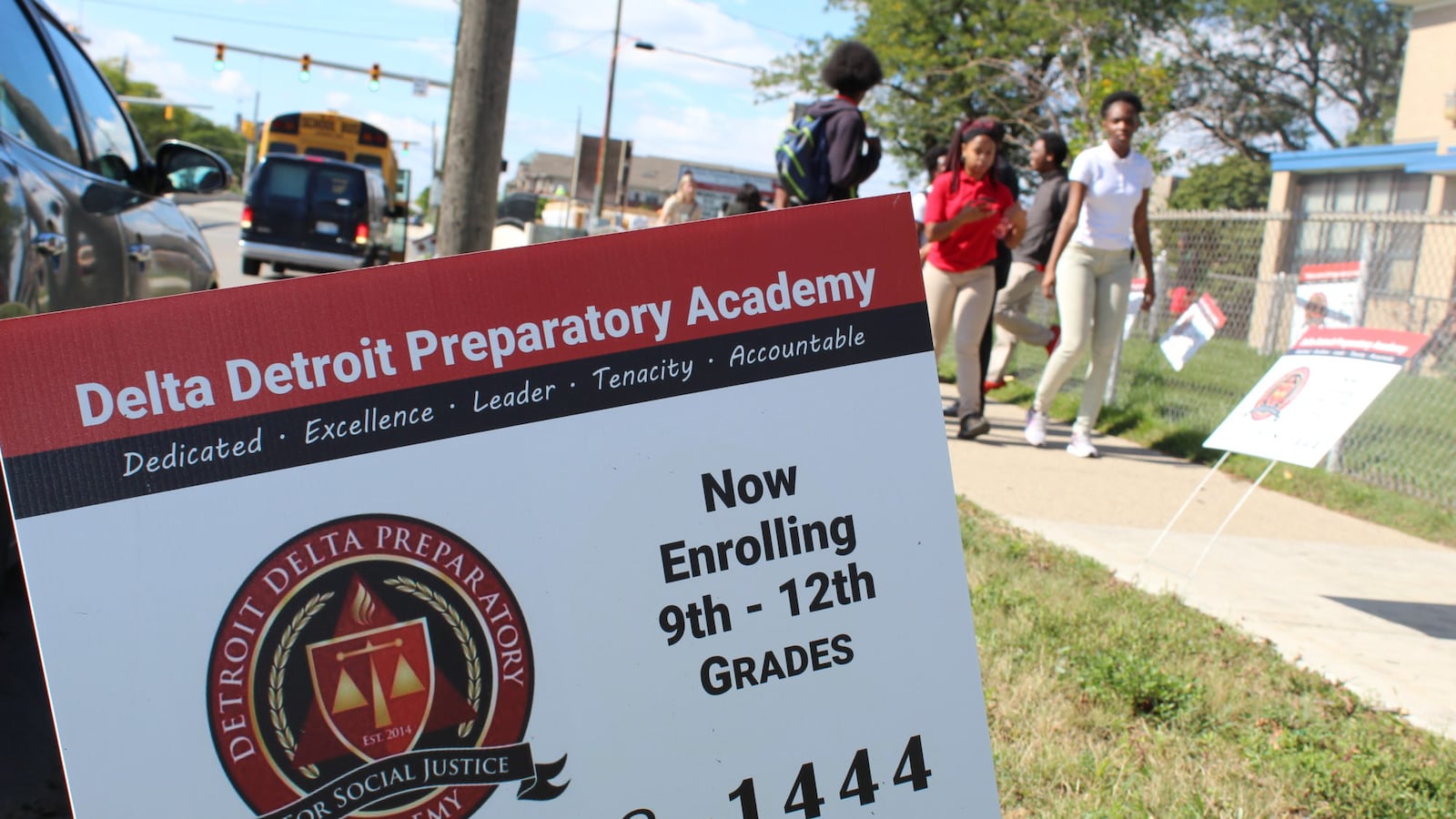

Just weeks after starting the school year, parents and students at the Detroit Delta Preparatory Academy for Social Justice got the stunning news Wednesday that their school will close next week.

“They’re devastated,” said Charlotte Jackson, a teacher who answered the school’s phone in tears Wednesday morning. “Students were very upset, crying, screaming, walking out, a whole lot of stuff … It’s not good.”

Students and parents learned about the abrupt closure — effective Oct. 1 — during a hastily-called, two-hour assembly with school officials Wednesday morning, including representatives from the school’s management company, EQUITY Education. Also present were officials from Ferris State University, which authorizes the charter school.

In the first two weeks of school this year, average attendance was just 180 students, down from 300 last year, according to EQUITY officials. In Detroit, where parents have many school choices but few quality options, schools can only guess at how many students will enroll before the start of a school year. And because Michigan schools get a set amount of money per for each student, a substantial drop in enrollment can wreak havoc on a budget.

“This year’s student count was far below what they had budgeted for,” said Ronald Rizzo, who runs the charter school office at Ferris State. “When all was said and done, they were too far below. They weren’t going to be able to make it financially so rather than see them perhaps struggle through the year with a sub-par education because of unavailable funds, they decided they would bite the bullet and, even at this time of year, which is terrible, give them the opportunity to go.”

The school was one of dozens in Detroit facing additional scrutiny from the state after several years of test scores that ranked in the bottom 5 percent of Michigan schools. It could have been forced to close if it failed to sharply improve student scores and reduce its suspension rate by a minimum of 20 percentage points. Last year, fewer than 10 11th-graders there passed state math and reading exams out of nearly 100 who took the test.

A letter from EQUITY that was distributed to parents at the meeting said the school’s board, not the people directly running it, had made the decision to close.

“It is neither the wish or will of EQUITY to close at this time,” wrote Renee Burgess, EQUITY’s president. “I believe it is wrong to educationally evict children from their school, particularly once the school year has started. The instability and trauma that is created when you close a school will remain with these children.”

After the meeting, Burgess told Chalkbeat that EQUITY offered the board several options that would have allowed the school to stay financially solvent and remain open for the rest of the year.

Kenneth Coleman, a member of the board of directors, blamed EQUITY for failing to prepare for the drastic decline in enrollment. He declined to comment further on why the school is closing.

“All I can say is that these kids were failed,” he said.

The shuttering of Delta Prep is the latest in a line of sudden charter school closures that have angered parents and raised questions about how well charter schools are managed and supervised in Detroit. Last year, a charter school just outside the city in Southfield closed with two weeks to go before the end of the school year.

Parents said they learned about the Wednesday morning meeting from their children the night before.

“We were blindsided, totally and completely,” said Avian Retick, whose daughter, Dezana Odom, just started her freshman year at the school.

Retick says the school seemed a step above her other options, and that officials with EQUITY assured her that Delta would give her daughter access to college preparation courses.

“They sold us on a lot of opportunities that aren’t going to come to pass,” she said.

Charter school oversight in Detroit got extensive scrutiny last year during confirmation hearings for U.S. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos who, as a Michigan philanthropist, has been influential in shaping education policy in Michigan.

Michigan allows an unlimited number of charter schools and doesn’t require the same level of oversight as other states, contributing to instability and uneven quality in the privately managed but publicly funded schools.

Rizzo defended the oversight his office provided to the school.

“They have been our list of schools that we have been supporting,” he said. “We have been sending folks over there to work with them on data analysis. We’ve been very engaged in trying to help the academy along.”

He said Ferris State would work with the state’s charter school association to help students find new schools.

“We are committed to doing everything humanly possible in the next several days to try to get students situated in new schools,” Rizzo said.

Delta Prep, a high school in Detroit’s midtown neighborhood, opened just four years ago with 46 students. It was the first school to be affiliated with the Detroit chapter of Delta Sigma Theta, a predominantly African-American sorority. Almost from the start, it was rocked by the same instability that it has now come to symbolize. When Allen Academy, one of the largest charters in the city, closed in 2016, a sizeable number of its students transferred to Delta, sending the school’s enrollment shooting to 333 in its second year.

Forced to expand too quickly, the school never found its footing, Monica Davie, a volunteer at the school, said.

“That explosion is what doomed it,” she said.

As its test scores floundered, the school had a new principal every year, said Diane Pompey, a parent liaison at Delta whose granddaughter has attended the school for four years. Pompey was a regular presence at the school, and many students called her “nana.” As seniors walked to their cars after the meeting, she called out to remind them to return the next day for their transcripts.

School let out for the day after the board decided to close the board next week. After the assembly, students spilled out onto the sidewalk in front of the school, waiting for a ride home.

“I can’t believe this is happening,” said TraVohn Rumely, a freshman. “Right now, I’d be in class doing work.”

“Laughing with my friends,” chimed in Kymia Latimer, Rumely’s older sister and a sophomore at Delta.

Around noon, school buses arrived to take some students home. Students who don’t live on the bus route said they’d have to wait near the school until 3 p.m., when school usually lets out, because their parents hadn’t been able to get off work early.

Talk on the sidewalk revolved around where students planned to enroll next. Schools were already competing for their attention — and for the roughly $7,000 in state funding that each additional student will bring to their new school. Students and parents said that Delta urged students to enroll in Detroit Leadership Academy or Detroit Collegiate High School, two other charter schools run by EQUITY Education. Others held handbills distributed by University Prep Science and Math High School, a charter school on Detroit’s east side. And in a tweet, the city’s main district said it’s ready to take students from Delta Prep.

Victoria Haynesworth, a parent at the school, said that officials discouraged students from applying to other schools, suggesting they wouldn’t get in.

“They were making comments about the fact that a lot of the school will not take the children because they scored very low on their tests,” she said.

While some of the city’s top high schools, like Cass Technical and Renaissance High School, require students to test in, most Detroit high schools do not consider test scores in admissions.

A woman who answered the phone at EQUITY Education’s office declined to comment but said she would pass along a request for information.

Steven McDuell, a senior who was entering his fourth year at Delta, said he planned to transfer to Old Redford with the rest of the football team, which had been busy preparing for the homecoming game scheduled for this Friday.

He echoed other students who left the meeting angry at the board for refusing to try keeping the school open for the rest of the year.

“They sat there and said, ‘We don’t care how y’all feel,’” he said. “It’s heartbreaking. Delta is all I know.”

As the school emptied out, Detre Holloway, a geometry and physical science teacher, left the school through the back door and walked to his car, exhausted by the emotional back-and-forth of the meeting. To Holloway, the reason for the closure is straightforward — there aren’t enough kids — and he brushed aside the question of who to blame for the school’s collapse.

‘“I am numb,” he said. “I saw a lot of finger-pointing back and forth. The kids saw it.”

Holloway and other teachers at Delta said they don’t expect to have any trouble finding another job in a Detroit classroom. City schools have struggled for years to find certified teachers, and there were roughly 90 vacancies in the main district on the first day of school.

For students, the closure marks a major interruption to schoolwork and friendships, and a forced departure from a school where many said they felt at home.

Haynesworth said her daughter, Gabrielle Doctor, started at the school in ninth grade and was crestfallen to learn she would not get to graduate with her class. Instead, Haynesworth is now scrambling to find her daughter another school she can attend.

“My daughter was hysterical,” Haynesworth said. “She was crying. Children were everywhere. It was hysteria. They were crying on the floor. Kids were beating on lockers.”

Gabrielle largely had a “really, really good experience” at Delta Prep, Haynesworth said.

Gabrielle, who was a majorette in the school band, has special needs that entitle her to a full-time aide who works with her throughout the day, and the school has been responsive to her needs, Haynesworth said. .

“I trusted the school with my child,” she said. “This is horrific. I’m furious. I’m emotional … I’m speechless.”

Myiel Commage, a senior who started at the school as a freshman, held back tears as she talked about the Delta marching band and her plans to start a step-dance team.

“I made so many friends here that were basically family,” she said. “That all got snatched away from me.”