This story is part of the series Moving Costs: How students changing schools disrupts Detroit classrooms, a joint project from Chalkbeat and Bridge Magazine.

By the time she’d reached the eighth grade, Shantaya Davis had attended so many schools — at least five — that she couldn’t name them all.

“I don’t even know what grade it was,” she said of one school, the one her mother decided wasn’t safe after she was threatened by a man in a car after class one day. “I just know I went there and it was like half a year … I went to a lot of schools. That’s why I keep forgetting.”

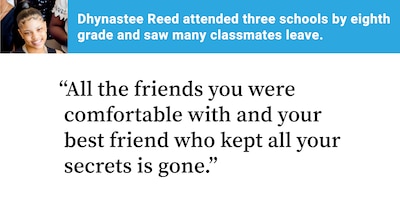

Her classmate, Shawntia Reeves, attended four schools on the way to eighth grade. Or maybe five. Her parents weren’t exactly sure of the details, beyond the fact that she’d started kindergarten at the small neighborhood school her family had attended for generations. When the district shut the school down to cut costs, she bounced around, forced to repeatedly make new friends, then lose them again.

“It makes you feel like you ain’t got no one to talk to,” she said.

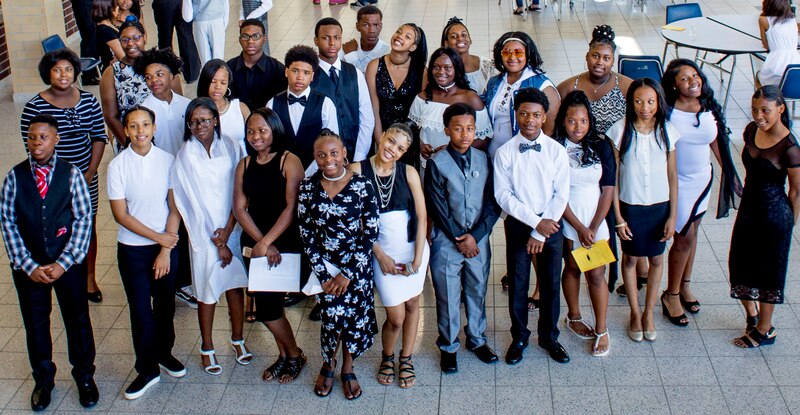

Both girls were members of the same eighth grade class at Bethune Elementary-Middle School in northwest Detroit last year. They posed with their classmates for a photo in June — a portrait of middle-school grads who looked like they’d known each other for years. But the 31 eighth-graders in Bethune’s “8B” homeroom had collectively attended a total of 128 schools — an average of more than four schools each.

Five of them said they’d cycled through seven or more schools on their path to eighth grade. Just three had attended the K-8 school since kindergarten.

These students are among countless others just like them in cities like Detroit — kids who’ve spent their childhoods starting over every couple of years, navigating new schools, trying to fit in.

Stories like theirs ripple through school districts across the country where the growing push to create new options such as magnet and charter schools has put an end to the days when most students enrolled in their neighborhood school. A comprehensive federal study that tracked a group of 20,000 children from 1998 until 2007 found that one in eight had attended four or more schools by the eighth grade. Those students were concentrated in large urban areas where people living in poverty are also grappling with evictions, foreclosures, and other forces that push people from their homes.

This kind of enrollment turmoil has a debilitating impact on schools, dragging down test scores, exacerbating behavioral issues, fueling dropout rates, and making it more difficult for all children to learn — not just those who are on the move.

In short, it’s a major — but often unrecognized — reason why improving urban schools has become one of the most intractable problems facing American cities.

“You can’t create trust between a student and parent and a school when you have this constant disruption,” said Nikolai Vitti, superintendent of the Detroit Public Schools Community District, which runs roughly half the schools in Detroit. “It’s hard to hold teachers accountable to performance if children are not consistently in their classrooms. We are going to set teachers, schools, and principals up for failure if we don’t acknowledge that.”

✴ ✴ ✴

The 8B homeroom started last September with 26 students. Then new faces began to appear.

Between November and June, one student came for a week, then left. Another left for a different school, then returned.

One new student didn’t join 8B until May 21 — just weeks before the eighth-grade prom and graduation.

By the end of the year, 11 of the 31 students had arrived at Bethune as eighth-graders.

In Detroit, there are many reasons why schools are in crisis. There are overcrowded classrooms and buildings in poor condition. There are children experiencing trauma at home, unable to find a quiet place — or a reason — to do their homework. But spend time in almost any Detroit school, and educators will tell you that perhaps the single most significant factor standing in the way of children’s success is this: Students don’t stay.

“It’s one of the most difficult things we deal with,” said Alisanda Woods, Bethune’s principal, who has led the 550-student school for the past two years.

Enrollment instability — often called student mobility — is not only under-discussed, it’s also inconsistently documented. That makes it difficult to clearly compare the problem across cities and states. But Detroit, along with Milwaukee and Denver, is among several big cities where nearly a quarter of students change schools every year.

And that average actually understates the problem in Detroit.

Here, decades of evictions, foreclosures, and financial distress have ravaged communities and destabilized housing. Nearly 200 school closures have distanced families from what used to be neighborhood schools. And state policies engineered in part by Michigan philanthropist Betsy DeVos before she became U.S. education secretary have created one of the most robust systems of school choice in the nation.

The effect: A recent analysis by two Wayne State University professors found that roughly one in three elementary school students changes schools every year — often in the middle of the school year.

Bethune doesn’t have the highest rate of student churn in the city — it’s fairly typical of district and charter schools in Detroit — but the long-struggling school housed in a stately red brick building sees new students arrive nearly every week of the school year, Woods said.

They turn up after moving from the other side of town, or arrive in search of better options after a bad experience.

At the same time, other students disappear. They’re in class one day, raising their hands to ask a question or volunteering to solve a math problem. The next day they’re gone, a single-day absence that soon turns to weeks. Staff often don’t know where they’ve gone until another school calls for their records.

“Four or five students a week are always coming or going,” Woods said. “We received new students this year all the way up to June where kids just showed up and then we were trying to figure out, ‘Should we pass this kid?’ How do we know?”

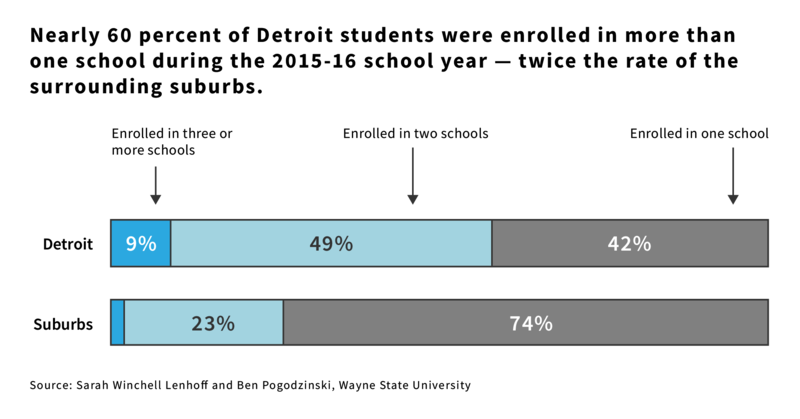

When the Wayne State professors, Sarah Winchell Lenhoff and Ben Pogodzinski, analyzed data from Detroit district and charter schools in the 2015-16 school year, they found that nearly 60 percent of students who live in Detroit — almost 50,000 children — were enrolled in two or more Detroit schools that year. Many had apparently boomeranged, returning eventually to the school where they started.

That includes nearly 7,000 children who were enrolled in three schools that year and some 900 children who were enrolled in four or more schools in a single school year.

“It’s a chaotic system,” Pogodzinski said. “If kids are moving in and out, you can’t build the systems in the school that are helpful and necessary to create a rich educational environment.”

That chaos means teachers don’t have the chance to make deep connections with their students.

It means new students are perpetually throwing off the dynamics of classrooms, forcing teachers, week after week, to shelve planned lessons so they can help new students get settled.

And it means that a significant share of the students who sit down every year to take annual state exams are children who could have fallen behind years ago, at another school. They might have arrived at their latest school just months before taking the exam.

Those exams are especially crucial for schools like Bethune.

The school, in a neighborhood that’s just now beginning to show signs of improvement after years of deterioration, was one of 38 Michigan schools threatened with closure last year because of persistently low test scores.

The schools were allowed to remain open — but only if they promised to show steady improvement on test scores over three years.

And while Michigan schools aren’t held accountable for the scores of newly arriving students, once a student has stayed long enough for her exam to count, children who are frequent movers are the most likely to struggle.

Research shows that students who change schools even once outside of routine moves such as between elementary and middle school have significantly lower test scores. They’re typically slower to improve academically than students who stay in one school. They have more behavioral problems and are more likely to drop out of school than their peers who stay put.

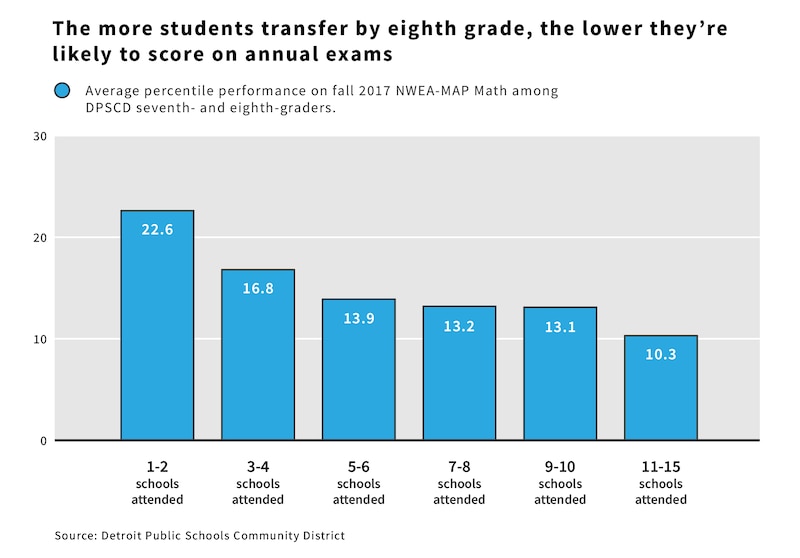

When the Detroit Public Schools Community District analyzed seventh- and eighth-grade student scores on tracking tests that schools use to figure out what students know, the trend line looked like a playground slide, with students who had attended just one or two schools at the top of the ladder, and those who’d attended the most schools down at the bottom.

Those transferring students are not the only ones suffering the consequences of instability. Studies show that even students who don’t themselves change schools are more likely to drop out if they attended schools where many classmates are coming and going.

“It has an impact on the students and it has an impact on the school environment itself,” said Richard Welsh, a professor of educational policy at the University of Georgia who has extensively studied the issue.

Students might benefit somewhat if they move from a low-performing school to a high-performing school, Welsh said. But in cities like Detroit, where the vast majority of schools are low-performing, most student transfers have largely negative consequences.

When there’s so much flux, Welsh said, teachers “have a hard time with momentum and a hard time with overall classroom management.”

✴ ✴ ✴

The students of 8B said their parents had good reasons for moving them from school to school.

Juliann Sanders, an 8B student who attended two charter schools before arriving at Bethune in sixth grade, said her mother pulled her out of her last school because she was alarmed by the conditions there.

“My mama said that school was ratchet,” she said, using a term for run-down or nasty. “It was dirty. She stopped making me go there because I was getting into fights and stuff.”

Jacob Cunningham, who attended a total of nine schools by eighth grade — the most in his class — attributed his moves to a mix of family housing issues and challenges at school.

He said he didn’t mind changing schools so frequently, but his mother, Angela Cunningham, said the moves were hard on him.

“It frustrated him,” Cunningham said. “He got attached to one school and he’d have to move. He’d rebel against it … He would get angry, just the idea of having to adjust to a new school.”

Many students said they transferred because of changes to their living situations, such as moving to a new house or leaving mom’s place to go live with dad.

But, like students across the city, changing homes was just one reason they moved around.

Lenhoff and Pogodzinski, the Wayne State professors, found that only about 40 percent of students in Detroit who changed schools between the fall of 2014 and the fall of 2015 had changed their address to a different ZIP code.

The rest transferred for countless other reasons. Their schools might have closed, which is what happened to roughly 200 students last week when a Detroit charter school abruptly announced it was closing its doors just weeks into the school year. Students might have been expelled, or otherwise encouraged to leave a school. Their parents might have grown frustrated with a teacher or administrator. They might have received one of the fliers that routinely show up on Detroit doorsteps advertising suburban schools, and decided to take advantage of an offer of free bus transportation.

Or they might have been turned off by policy moves, such as the state of Michigan’s decision in 2012 to seize Bethune and 14 other low-performing schools to put them in a controversial state-run recovery district. When the schools returned to the main Detroit district last year, some students who went to Bethune the previous school year were told that busing zones had changed and they no longer could ride a yellow bus to school.

A survey of 100 Detroit families conducted by Chalkbeat and the nonprofit news service Outlier Media found that one of main reasons families changed schools in Detroit was because they were dissatisfied with the quality of instruction in their child’s school.

[ Read more: Detroit makes it easy to switch schools. So parents do. Frequently. ]

And when Detroit parents aren’t satisfied, they can leave.

Michigan’s educational system allows for an unlimited number of charter schools, and lets families cross city lines to enroll in neighboring districts. The system encourages families to shop around for the right choice.

But in a city where most schools are struggling, parents wanting the best for their child might not be happy with the first, second, or third school they try. They might keep searching, and might end up causing serious harm.

“They’re taking a risk with little evidence that these different schools they’re enrolling in are going to be that much better for their child,” Lenhoff said. “And they’re maybe not fully aware of the potential harmful effect of the move itself.”

✴ ✴ ✴

It was November when Gabrielle Elliott joined homeroom 8B.

For years, she had attended the Marvin L. Winans Academy of Performing Arts, a charter school on the city’s east side where her parents hoped she’d be able to finish middle school.

But when a sudden housing emergency in April 2017 forced the family to move to the city’s west side, that became more difficult. Gabrielle’s parents made the 35-minute drive to her old school every morning until November when winter road conditions made the drive impractical.

Gabrielle would have to spend the last seven months of eighth grade at Bethune.

“I was nervous,” she said of her first day in a new school, recalling sweaty hands and a bouncing heart. “I’m a nail-biter.”

Though she knew some of her new classmates from an earlier stint at Bethune in the fourth grade, that first day was daunting.

In her English class, she sat alone on one side of the classroom, a look of fear on her face and a blank sheet of paper on her desk. All around her, eighth-graders were writing in their workbooks. But Gabrielle hadn’t gotten a workbook yet, so she sat and watched.

In science class, she spent the period nervously glancing around the room, chewing on a wad of gum during a lesson on magnetism.

It wasn’t until students were lining up at the door that her new science teacher asked if she was visiting from another class.

“No,” Gabrielle answered, “I’m new.”

“Oh,” her teacher said. “Welcome.”

In a perfect world, each of Gabrielle’s new teachers would have gotten the word that a new student was coming, maybe even had a chance to review her transcripts.

But, in Detroit, so many new students arrive so frequently, teachers say they’re often blindsided by new arrivals.

Lydia Nickleberry, a second-grade teacher at Bethune, said she returned to her classroom after meeting with a parent last winter to find a new student sitting in her class.

“That was in January,” she said. “At that point I had 32 students and she was number 33 and I said, ‘I don’t have a desk for her.’ I have to go get a desk, get a chair.”

Nickleberry said it takes her roughly two weeks to figure out what new students need.

“It makes it hard because there’s gaps in education,” she said. “One student, he came in December, I had to go and ask if he had a history of some type of [disability] because obviously not everything clicked. It was hard for him to understand basic questions.”

[ Read more: The heartbreak and challenge for teachers in schools where students are on the move ]

When a new student transfers into the school, paperwork documenting student disabilities and spelling out therapies and support for those children is supposed to come with them. The child’s former school, when requested, is supposed to send over transcripts, test scores, and other paperwork.

But teachers say it can take weeks to get a student’s transcript from another school, even from other schools in the same district.

The state education department is developing a centralized data system that, in the next few years, will enable schools to quickly access the records of new students.

But for now, schools must make the request, then hope for a timely response.

If it takes too long, the new teacher might never know if the child who just arrived had behavioral problems in her last school, or if his last teacher thought he might need glasses.

Student transience affects nearly every school in Detroit, yet few schools have any kind of formal system or specialized training for teachers to help them support the students who show up halfway through the school year. That’s despite the fact that new students are often reeling from a sudden move.

“Some of these kids have a lot of problems that nobody’s addressing, and they’re coming in and a lot of times they’re unstable,” Woods said. “Our teachers will receive these children and work with them from the time they walk through the door until the time they leave … But then new students arrive and we have to start all over again.”

At Bethune, when parents report a new student has emotional issues, someone from the school’s “culture and climate team” typically meets with the new student to explain the school’s expectations and ease the transition, said Alisha Webster, who was the school’s social worker last year.

She did group therapy and one-on-one counseling to support children in the school, she said.

But it can be hard to make much progress with students who might not stay long.

“It’s like treading water,” Webster said. “They enter with social issues, trying to fit in and not be bullied. But how can they stay focused if they’re constantly catching up?”

✴ ✴ ✴

The children of 8B showed up at graduation looking their best. The girls wore fresh hairdos and wobbled around in high heels; the boys wore pressed pants and dress shirts.

Gabrielle got stylish new hair extensions for graduation, wearing her hair in long, wavy curls for the big day. She’d ended the school year feeling like she’d made friends and gained a bit of popularity.

She had a few academic setbacks at Bethune, like a project she failed to finish for a science fair. After the fluctuation in her grades, she had to file an appeal to try to get into Cass Technical High School, one of the city’s top high schools.

In the end, she’d found a way to fit in at Bethune and was planning to enroll at Cass this fall.

“Now I’m more relaxed,” she told a reporter in May. “People ask me to sit with them. People want to be my friend.”

By graduation day, some of her classmates still weren’t sure what high school they would go to next. They have choices, after all, Woods said.

Ads for online schools, charter schools, and suburban schools would soon be running on the radio to lure families out of the Detroit school system for high school.

As the kids milled around the common area at Mumford High School, where Bethune’s eighth-grade graduation took place, Woods’ eyes settled on Jacob, the boy who had been to nine schools.

Where would he end up next? Which high school would he graduate from?

Would a child who moved through so many schools sit still long enough to graduate on time, she wondered.

All she could do was hope.

“I pray for him,” Woods said. “I pray for all of them.”