Four major providers of Head Start programs in Detroit must re-apply for funding after losing their federal grants this year, throwing the future of dozens of classrooms in doubt for the fall.

One of the four providers was forced to re-compete for funding after leaving a 3-year-old outside in freezing winter weather and putting children in unsafe classrooms. The other three were ranked poorly in a federal performance review that scores how students and teachers interact.

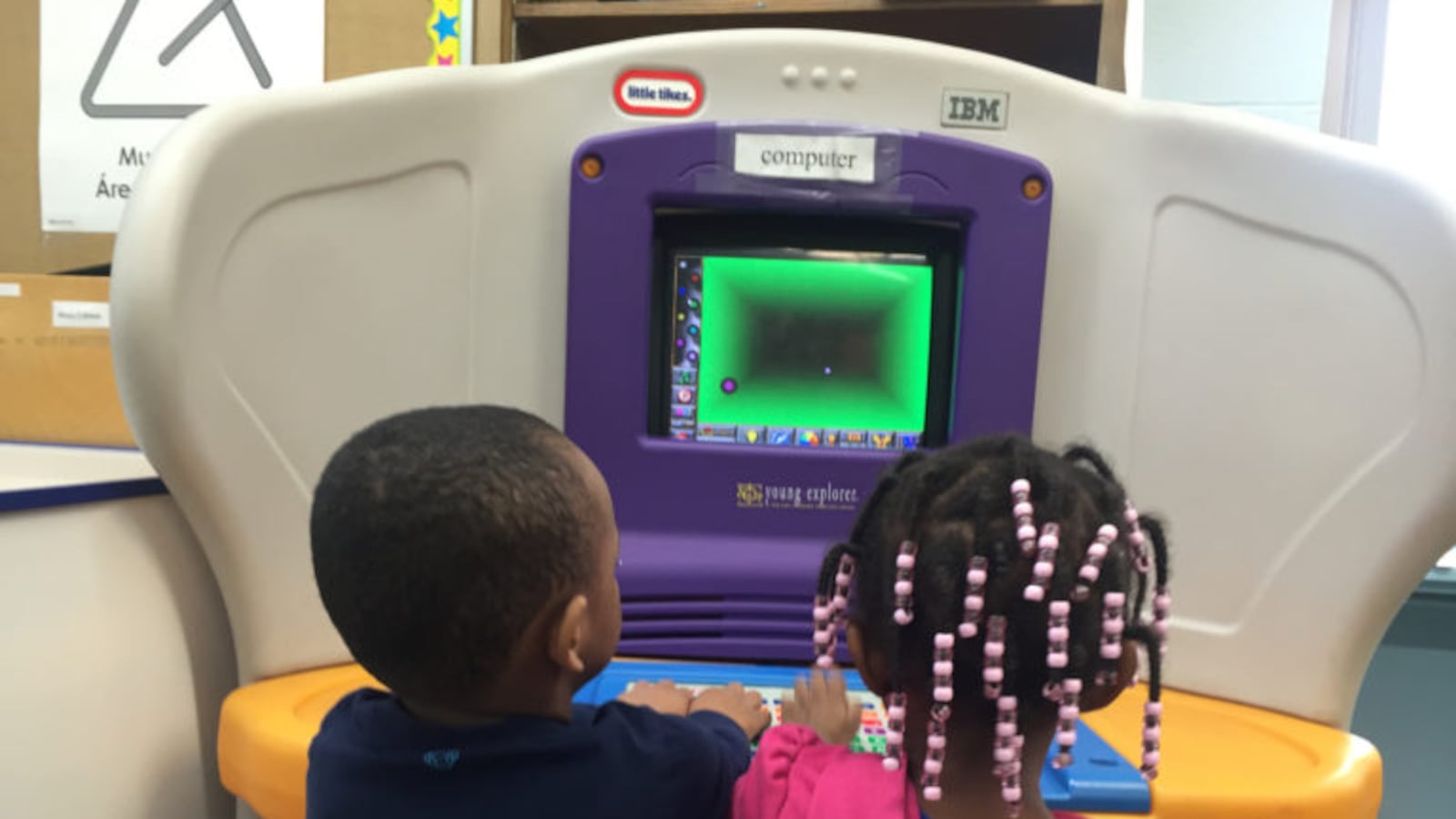

Head Start, the federally funded program that provides free preschool and other services to the nation’s neediest children, has long struggled in Detroit. Years of program neglect while under the supervision of a cash-strapped city agency left providers without adequate buildings and a teacher shortage so severe that two years ago, 800 funded seats for the most vulnerable children in the city were going unused.

Since then, the program had expanded, but providers are still struggling to create enough programs to use all of the 5,200 Head Start seats the federal government would fund. As of last spring, 260 seats were going unused, according to Patrick Fisher, spokesperson for the Administration for Children and Families, the federal organization that oversees Head Start.

Thousands of Detroit families rely on these programs for free childcare and meals for ages 0 to 5. Head Start is especially important for low-income families struggling with the skyrocketing cost of childcare. Despite the longstanding issues, these Head Start facilities are many families’ only option for affordable quality early childhood education. Studies on Head Start show the program can influence everything from whether kids succeed in school, to whether they become smokers as adults.

While federal Head Start funding will continue to flow to Detroit, the organizations currently providing the program could be pushed out. That could force some classrooms to be closed or moved — a prospect that has been unsettling to families who might not be able to bring their children to a school that’s farther away.

“It would definitely be a disruption because I would have to travel, and a lot of us don’t have the means to travel,” said Monika Chester, the mother of three children who attend Head Start at the Samaritan Center on Detroit’s east side. “A lot of us are walking, taking the bus, getting a cab, even in the winter, and my baby is five months old.”

“But the worst thing would be for my babies to adapt to new teachers,” she said. “That’s the worst. That’s really bad.”

The four providers that must recompete — Matrix, Starfish Family Services, New St. Paul Tabernacle Head Start Agency Inc., and Metropolitan Children and Youth, Inc. — must divert attention from running facilities to competing for the federal money that allows them to run the programs.

The process to reapply for one of the five-year grants is significantly easier if providers have no issues with their federal scores, providers say. Meanwhile, providers who score in the bottom ten percent on a federal ranking or have other issues are forced to undergo a multistep process that can take several people a month or longer to complete.

Ann Kalass, whose Starfish Family Services leads the coordination of a large Head Start collaborative called Thrive by Five Detroit, said her biggest concern is how reapplying affects the children and families in the program, rather than the time it takes for staff to reapply.

“What I worry about is that it creates a disruption and they leave our programs in May and June not knowing who to count on in the fall,” said Ann Kalass, who runs Starfish Family Services.

“There is a lot of work going on among many providers to submit quality plans and applications in mid-January, so yes, it’s definitely taking resources for us to do that,” Kalass said. “But from my perspective, we do this work all the time — we’re always competing for grants and new opportunities, so it’s people spending time on writing grants who might otherwise be thinking about the program strategy and implementation.

“The real concern for me at a system level is that we’re trying to rebuild and reinvest and it feels like taking a step back to move a step forward,” she added.

The federal auditors grade classrooms in three categories: emotional support, classroom organization, and instructional support. Providers are compared against one another nationally, and the lowest scoring 10 percent must automatically rebid for the federal money that pays for the program.

In the category of classroom organization, Matrix, Starfish, and New St. Paul all scored in the bottom 10 percent range nationally.

Kalass said teacher turnover played a role in why the scores were so low in that category.

“Classroom organization looks at the routines and the structures of learning in the classroom,” Kalass said. “It talks about routines in the classrooms, the overall management of what’s happening in the classroom, and we have a high level of teacher turnover in the city, and some of the highest rates of teacher turnover in the country.”

The median salary for a preschool teacher who works full-time in Michigan is less than $30,000 a year, according to one study, making it hard to retain teachers. A report from the Kresge and Kellogg foundations pointed to the shortage of qualified preschool teachers as one of the challenges to improving early education in Detroit.

The next category, instructional support — how children are taught — “involves how teachers promote children’s thinking and problem solving, use feedback to deepen understanding, and help children develop more complex language skills,” according to a guide to understanding the scoring metrics.

Nationwide, providers struggle to post high scores for this category. The passing score has a low threshold — it is only about 2.31 out of seven. Similarly, in Detroit, all four providers had low scores, but New St. Paul fell below the threshold for passing in that category.

In the emotional support category, all of the providers in Detroit scored above the minimum. This area measures how teachers “help children resolve problems, redirect challenging behavior, and support positive peer relationships.”

The federal Office of Head Start, which conducts the reviews, has proposed a change to the bottom 10 percent rebid rule and other scoring guidelines, but it won’t have an effect on the current process.

Providers in Detroit support the change. They believe comparing the city with providers outside of the area isn’t right. Last year, 32 percent of grantees nationwide had to recompete for grants. In Detroit, that number is higher as providers struggle with crumbling buildings, high teacher turnover, and a Head Start program that has endured years of turmoil.

But the other issues submitted to the federal office by the facilities themselves are harder to debate.

At the Samaritan Center, a Matrix facility on the east side near Chandler Park, on Jan. 8, 2018, a teacher was terminated after kicking a 2-year-old who fell asleep in a chair, according to the federal report released in February. The Samaritan Center had another violation in October of last year, when a 3-year-old was told to walk back to class unsupervised and was later found by personnel “alone, lying on the floor in a classroom crying,” according to a May report. The teacher was terminated.

The Eternal Rock Center, another Matrix facility located in Southwest Detroit, was given a violation after a 4-year-old was left in a classroom unsupervised for a short time in January. The teacher was terminated in this case as well.

Matrix officials say they systemic improvements at all of their facilities. The office of Head Start later found that all issues had been effectively corrected.

A report on the Metropolitan Children and Youth, Inc.’s facility was enough to trigger the contract rebid process. In winter of 2014, at the Harper/Gratiot Center on Detroit’s east side, a 3-year-old was left outside on a playground and later found by a parent crying and knocking on the door of the building. Neither the center’s investigation nor a review by the federal office was able to determine how long the child was outside in freezing temperatures.

Only Metropolitan Children and Youth is forced to rebid because of the offsite reports.

“Reviewers examine documentation sent by the grantee to identify program strengths or weaknesses, deficiencies, or that an issue has been remediated,” said Patrick Fisher, a spokesperson for the Administration for Children and Families, the federal office that oversees Head Start.

In Detroit’s Head Start classrooms, reported treatment like this is rare but not out-of-the-blue: underpaid teachers working in buildings struggling to keep the heat on sometimes results in poor conditions.

If the four providers don’t manage to win contracts, families could be forced to find new centers and forge new connections with teachers. Moving locations can be hard on families and children alike, and requires a concentrated effort between the old and new provider to successfully transition students and staff.

A transition occurred last year after Southwest Solutions abruptly shuttered 11 Head Start centers. Luckily for the 420 children affected, Starfish Family Services was able to transition the children and many of the teachers to other agencies, allowing many to remain in their existing facilities.

There’s no guarantee that relocation of families could happen so smoothly in the future, but the Detroit providers are keeping lines of communication open.

“I think there are a lot of encouraging signs for early childhood programing in Detroit,” Kalass said. “Providers are meeting monthly to problem solve together — around workforce, facilities, and about better connecting with families.”

“We’re in a place of rebuilding and I’m optimistic that we won’t see a situation like this again. We won’t be in this place a few years from now.”

Scroll down to read some of the reports that led to one Head Start agency being asked to reapply for funding.