A small program that started in Detroit last year with an innovative plan to improve infants’ language skills has proved promising and is preparing to expand.

When Concepción Orea entered the program, LENA Start, with her 18-month-old son, the boy was making a few simple sounds. She worried that he was displaying the same delays as her older son, a kindergartner who receives speech therapy.

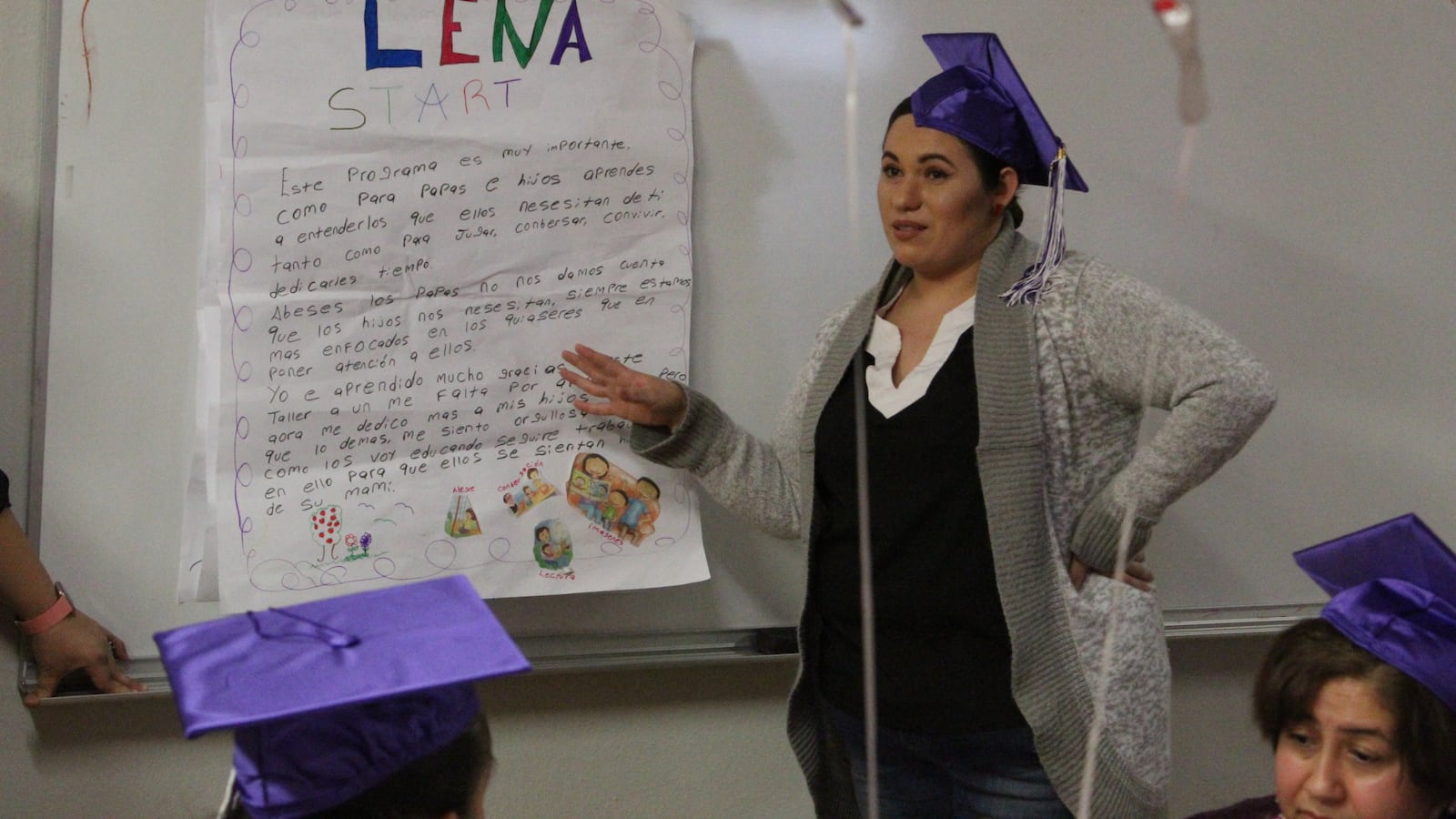

“Now he grabs a book and pretends to read,” she said, speaking in Spanish at a graduation ceremony for the program on Tuesday. “Watching him pick up more sounds … it’s an emotion I don’t know how to explain.”

Over the course of the free 13-week program, Orea was coached to speak more to her child and read books to him. Her son was outfitted with a recorder that shows his — and her — progress. Each family is asked to place a recording device in a bib near their child’s chest, where it tracks and analyzes the sounds the baby hears at home.

The approach is based on research showing that when parents make a habit of talking to a very young child, that child is more likely to learn to read on grade level, with all the long-term benefits that come with literacy. That’s a big deal in all of the 20 cities where LENA Start operates, but the stakes are even higher in Detroit, where a tough new “read-or-flunk” state law, taking effect next year, will tighten the screws on a citywide literacy crisis.

“What our data are telling us is that for every one month in LENA Start, there are two months of growth,” said Kenyatta Stephens, Chief Operating Officer of Black Family Development, Inc., one of the program’s funders.

Growth, in this case, mostly means an increase in language comprehension and “turn-taking,” a verbal back-and-forth between parents and children that researchers view as an important sign of healthy language development. Parents are trained to verbalize their thoughts to their children, then look for a response.

A rise in turn-taking also correlates with other benefits: Parents talk to their children more frequently, for one, and kids are exposed to less electronic noise from TVs or cell phones over the course of the program. LENA gives books to parents, and parents typically report reading aloud more to their child.

The program started in Detroit last year with 50 parent-child-pairs. Thanks to promising results, LENA Start’s nonprofit supporters — including Black Family Development, the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, the LENA Foundation, the Michigan Children’s Health Access Plan, and Brilliant Detroit — plan to enroll another 150 parent-child pairs in Detroit.

(The W.K. Kellogg Foundation funds Chalkbeat. Read our code of ethics here.)

Program leaders say they hope to keep expanding, though the recording technology is pricey.

Using the bib recordings, LENA Start’s computers produce a detailed report for parents. It tells them how much electronic sound the baby is hearing (differentiating between a computer and a live voice), how much the baby is speaking, and how often the baby “takes turns” in conversation with someone else in the home.

The program draws on the research of Betty Hart and Todd Risley, the source of the much-cited notion that children from poor families typically hear 30 million fewer words before age three than their non-poor peers. That statistic went viral in academic and nonprofit circles, but it has come under fire in recent years, partly thanks to data collected by LENA programs, which pointed to a gap that is probably closer to 4 million words.

The challenge for program managers in Detroit is working to close the gaps that do exist while rejecting the idea that poor families do less for their children. Framing the problem as a “word gap” can be discouraging to parents and can even cue educators to expect less from children whose families live in poverty.

That may be why Stephens sees the recording data as “an affirmation tool.” Even when parents are stretched thin by poverty, she says they are able to change their speaking habits, especially when they’re given evidence that it is helping their child.

“What’s important is that we’re affirming that they’re already their child’s best teacher,” she said.

That may be one reason that Detroit’s program boasts an unusually high graduation rate — upwards of 90 percent of families compared to the national average of 80 percent.

Graduation ceremonies tend to be loud, Stephens said, because babies become more vocal over the length of the program.

Yuliana Moreno, one of the graduates, entered the program almost by default. She was already at Brilliant Detroit’s Southwest Detroit location at least twice a week before she entered LENA Start, attending infant massage classes for her seven-month-old and English classes for herself.

She said the benefits of the program extended to both of her children, even the one who didn’t attend LENA Start with her. It’s not that she wasn’t talking to them before — it’s just that no one had told her how important her communication could be, and the normal demands of life got in the way.

These days, she reports reading to her children more often, and says she uses her cell phone less while they’re around.