Gov. Gretchen Whitmer is set to propose the most dramatic shift in Michigan’s school funding formula in years — calling for a weighted system that would pay schools more for low-income and special education students, who are more costly to educate.

Whitmer is also calling for an overall funding increase of $120 to $180 more per student, according to an outline of the plan reviewed by Chalkbeat. The big question is whether the plan from Whitmer, a Democrat, will face opposition from a Republican-controlled Michigan Legislature.

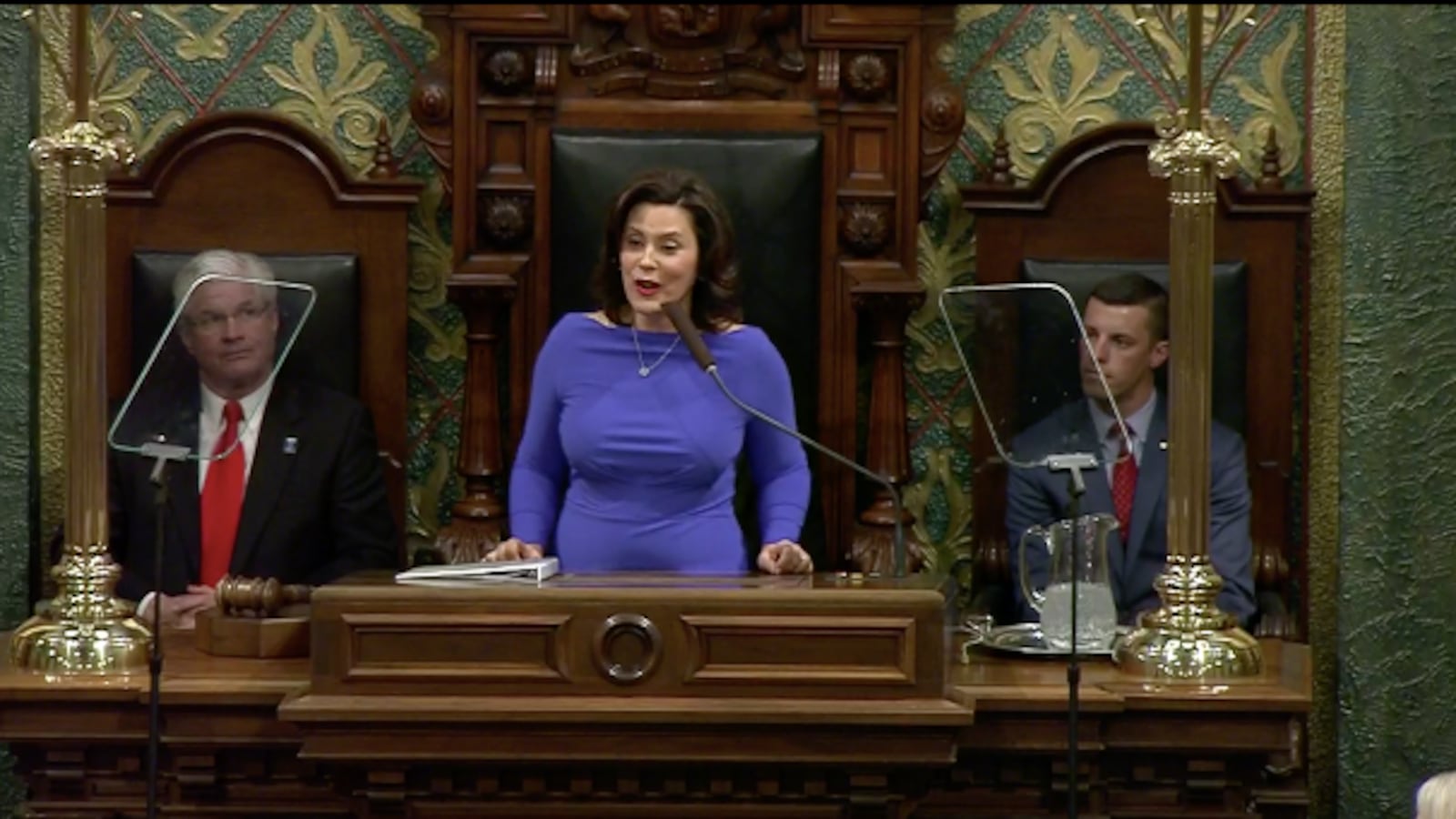

The proposal was first reported by the Associated Press Monday. Whitmer is expected to formally introduce her budget proposal Tuesday. The AP said Whitmer’s administration is billing it as the largest increase in classroom spending in 18 years, if state payments for retirement are not counted. The overview from the governor’s office didn’t offer details on how Whitmer would pay for the increased funding.

The move brought applause from school leaders who’ve been pushing the state to fix the state’s funding system for schools, though some noted that even more funding increases are needed.

“This is the right direction for the future of Michigan’s schools,” said George Heitsch, president of the Tri-County Alliance for Public Education, a group that represents the interests of schools in Macomb, Oakland and Wayne counties. Heitsch is superintendent of Farmington Public Schools.

Repeated increases in school funding in recent years have not slowed calls for more money, with critics pointing out that overall funding has not kept pace with inflation since the current system was put in place 25 years ago.

Matt Gillard, president of the advocacy group Michigan’s Children, applauded Whitmer’s call for increased funding but noted that her proposal does not represent the drastic increase that many experts argue is necessary.

“I don’t think this will solve all the financial problems facing our education system,” he said. “But it’s a good first step.”

Here’s what you need to know:

Weighted funding

The overview describes the funding proposal as “the first step in implementing a weighted per-pupil funding system.”

Michigan already provides additional funding for some costly students, but Whitmer’s proposal would take it to another level, in part by building the additional funding into the school funding formula, rather than by providing it to districts as part of a separate grant. She would provide $120 million more statewide for special education, $102 million more for low-income and other at-risk students, and $50 million more for career and technical education students.

The proposal comes after two studies in recent years found Michigan’s school funding system to be inadequate and unequal. In the most recent study, completed by the School Finance Research Collaborative, there was a strong push for a weighted formula for school funding.

David Hecker, president of the American Federation of Teachers-Michigan, said Whitmer is taking an initial step “toward what we need, which is to make sure students get the education they all deserve.”

Hecker, who was part of the school finance research group, said he pleased that Whitmer, “said she was going to be an education governor … and she’s delivering.”

It would take a much larger funding increase to meet the research group’s recommendations, which could cost $3.6 billion, according to analysis in a recent report from Michigan State University researchers who found Michigan ranks last among states for total revenue growth for schools in the last quarter century.

Ben DeGrow, director of education policy at the Mackinac Center, a libertarian-leaning think tank, said Whitmer’s proposal doesn’t get close.

“[The proposal is] pretty standard, so if she’s trying to meet the recommendations of the collaborative, it doesn’t look like something she wants to take on in her first year,” DeGrow said.

Special education

Federal law requires schools to provide special education services to eligible students. But neither the state nor the federal government provide enough funding to cover the full cost, which means schools make up the difference by using general education funding.

Michigan currently reimburses districts for 28% of their special education costs, one of the lowest reimbursement rates in the country (the federal government is supposed to reimburse 40 percent of the cost, but only covers about 14 percent). Under Whitmer’s plan, the state reimbursement would increase by 32%.

The overview from Whitmer’s office says the additional money for special education would mean districts could “provide additional intervention and support staff for special education students, while also freeing up school operating dollars to improve education for all students.

A 2017 report from a special education task force headed by former Lt. Gov. Brian Calley concluded that special education in Michigan is underfunded by $700 million.

“Michigan is not very generous towards special education,” said Mike Addonizio, a Wayne State professor who was also part of the school finance research group. He said the state’s reimbursement rate needs to increase higher than Whitmer is recommending, but “given the revenue constraints that the governor has to operate under, I can understand why the recommended increase isn’t bigger than it is.”

He said the special education cost in Michigan especially burdens large districts like Detroit’s public school district, which has lost a number of students to charter schools in the last two decades.

“Districts like Detroit are left with an inordinately high proportion of students with special needs,” Addonizio said.

Low-income students, at-risk students

Currently, the state provides $517 million in funding for at-risk students, which provides about $746 for every student who meets the criteria. Whitmer’s proposed increase would take it to $894 per pupil.

Students are eligible for the at-risk funding if they meet one of a set of 10 criteria that include being economically disadvantaged, an English language learner, chronically absent, a victim of child abuse or neglect, and a pregnant teen or teen parent.

In Michigan, students are identified as economically disadvantaged, for funding purposes, if they are eligible for the federal free or reduced price lunch program, which means their family income is between $36,630 to $46,435 for a family of four. They can also be identified as economically disadvantaged if their households received food or cash assistance, if they are Medicaid-eligible and living at the federal poverty line, and if they are homeless, migrant or in foster care.

Career and technical education students

Currently, the state provides about $50 per student for career and technical education programs. The increase in Whitmer’s proposal would take it to $487 per student.

Whitmer, like her predecessor, sees these types of programs — which provide students with technical training in a number of fields — as a way to narrow the statewide skills gap and increase the number of people trained to meet the needs of Michigan’s employers.

Overall funding

School districts and charter schools that currently receive the lowest per-pupil grant would see the biggest increase in funding — $180 per student. That would bring their annual state grants to $8,051 per pupil. The districts that receive the maximum grant — per the 1995 state funding formula that allowed some districts to continue spending at higher levels – would receive an increase of $120 per student, to $8,529. Some districts spend even more, because the funding formula allows them to levy additional taxes for schools.

According to the overview, the increase “reduces the gap between the highest and lowest funded districts to $478 per pupil.” The overview says that’s an 80 percent reduction in the gap since the mid-1990s, the last time there was a big change in the state’s funding formula.

Literacy coaches

The AP reported that Whitmer will also recommend tripling the number of literacy coaches statewide from 91 to 279. That could be crucial given the high-stakes portion of the state’s third-grade reading law. Beginning with the 2019-20 school year, schools must hold back most third-graders who are a grade level or more behind in reading.

Politics

Does Whitmer’s plan stand a chance before a Republican-controlled Legislature? That remains to be seen. Lawmakers could be pushed by multiple coalitions that have called for a change in the way schools are funded. Some have outright called for a weighted funding formula, while others have pushed for Michigan to ensure equity in the way schools are funded.

DeGrow said he expected that the basics of the proposal had a good chance of winning support in the legislature.

“There doesn’t seem to be anything drastic or radical here,” he said.

Addonizio, the Wayne State professor, said he believes the public is starting to understand the impact of higher class sizes, a lack of support staff, and special education students not getting the services they need.

“It’s clear to a lot of us that these lack of resources are showing up in poor performance of our students on reading tests and math tests.”

Meanwhile, Addonizio said, the state’s business community has been vocal about the difficulties they’re having “finding the talent they need to compete.”

“The time is right now for a realistic discussion of the revenue needs for the state,” Addonizio said.