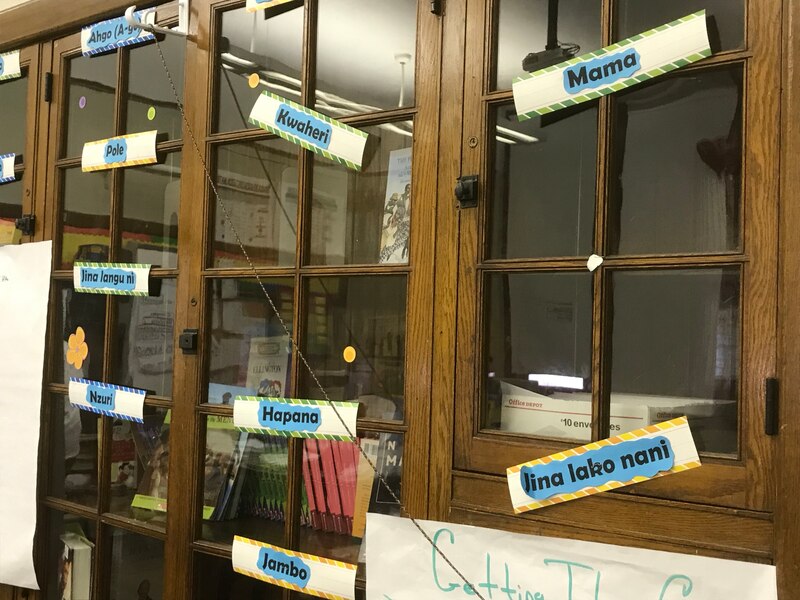

There are African words on the wall. Books by African-American authors in the cabinet. Posters of notable African-American scholars on the walls. But much of what makes this an African-centered classroom is what happens when teacher Welia Dawson and her students are breaking down a poem by the English poet Rudyard Kipling.

This poem called “If” — written in the form of advice from a parent to a son — is part of the required school district curriculum. But as her students are talking about how perseverance is a theme in the poem, Dawson relates it back to another poem — this one written by the African American poet Langston Hughes.

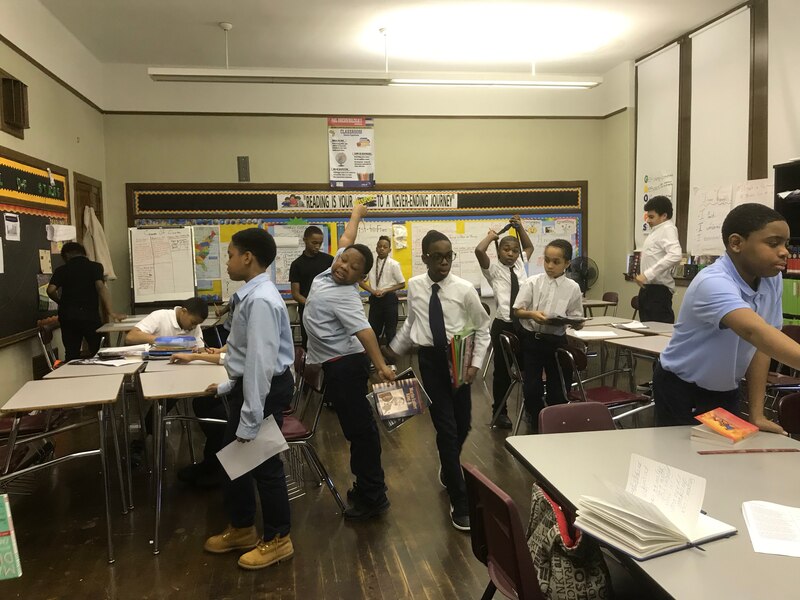

“In ‘Mother to Son,’ isn’t she saying the same thing to her son?” Dawson asks the students in her all-male English language arts class at Paul Robeson Malcolm X Academy, before taking the conversation to a deeper and more personal level.

“That’s something that as African American males, you need to realize,” she tells the sixth-graders. “Life for you is not going to be easy. That’s why you have to strive or work even harder to prove to the world what you’re made of. You don’t give up when times get hard.”

Schools like Paul Robeson Malcolm X, with its African-centered approach to education that is built around the notion that black children need to understand their history and culture to succeed academically, made a Detroit a leader and spurred districts in other parts of the country to replicate the approach. The school’s principal, Jeffery Robinson, is among those hoping to see a resurgence of African-centered education in the Detroit school district, something he believes could boost achievement in the struggling district.

“This is an opportunity for Detroit to return to some innovation and some pioneering that it once embarked upon at the onset of African-centered education,” Robinson said earlier this month during the first of a series of six professional development sessions that he hopes will be the start of that resurgence. Robinson has spent much of his 28-year career in African-centered schools — both as a teacher and as a principal.

“African-centered education is part of the positive legacy of DPS,” Superintendent Nikolai Vitti said. “It’s important to our reform to preserve and expand the principles of the philosophy because it empowers our students to better understand who they and who they aren’t.”

The professional development sessions are attracting veteran African-centered teachers like Dawson, as well as those who teach in traditional school settings.

Catena Alexander is one of them. Alexander, a special education teacher at Fisher Magnet Lower Academy, came to the first session hoping to learn ways to incorporate some of the practices with her kindergarten students.

She already has a long history with African-centered education. Her youngest daughter attended a charter school that used that approach, before Alexander even became a teacher.

“Their entire approach to education is entirely different,” Alexander said. “It gave my daughter a different sense of pride. It gave her a different sense of self.”

Back when her daughter was attending Nsoroma Institute, a charter school that has since closed, the city of Detroit had well over 20 African-centered schools. The school district alone had 13, but only two remain — Paul Robeson Malcolm X and Garvey Academy.

Robinson said he’s hoping that attendance at the training sessions will demonstrate interest among teachers.

“What we’re trying to do is work with [Vitti] to train teachers in what I truly feel has been missing and is key to turning around our test scores,” Robinson said. “By and large, our children have not seen themselves in the curriculum. The curriculum doesn’t reflect their lived experiences.”

At the district level, Vitti said there’s a need to strengthen the African-centered focus at Garvey “so it can offer another model for school reform as” Paul Robeson Malcolm X does. Vitti said he hopes that effort will increase enrollment at Garvey.

And the expansion of professional development, he said, is being done “to improve instruction and relationships with students in non African-centered schools throughout the district.”

During the first of the six trainings sessions, held earlier this month at Robinson’s school, several dozen attendees heard from Chike Akua of the Teacher Transformation Institute. Akua has been working with Paul Robeson Malcolm X staff for years already.

“Our children are brilliant,” Akua told the audience. “But many of them are in schools or school systems where they’re seen as a problem, rather than as people.”

Meanwhile, he said, black youth grow up in a society that has “gangsterized and criminalized young black males,” and “objectified and sexualized young black females.”

“Most of our children have not been exposed to the best of our culture. They’ve been exposed to the worst of our culture.”

He defined African-centered education this way:

“The process of using the best of African culture to examine and analyze information, meet needs and solve problems in African communities.”

And he outlined 13 essential elements of African-centered education, including placing Africa, African people, and African points of view “at the center of all things studied. In other words, it makes what we learn relevant and responsive to our needs.”

Akua said putting African points of view at the center is important because “most of what we learn in standard American curriculum … places us at the margins or in the periphery.”

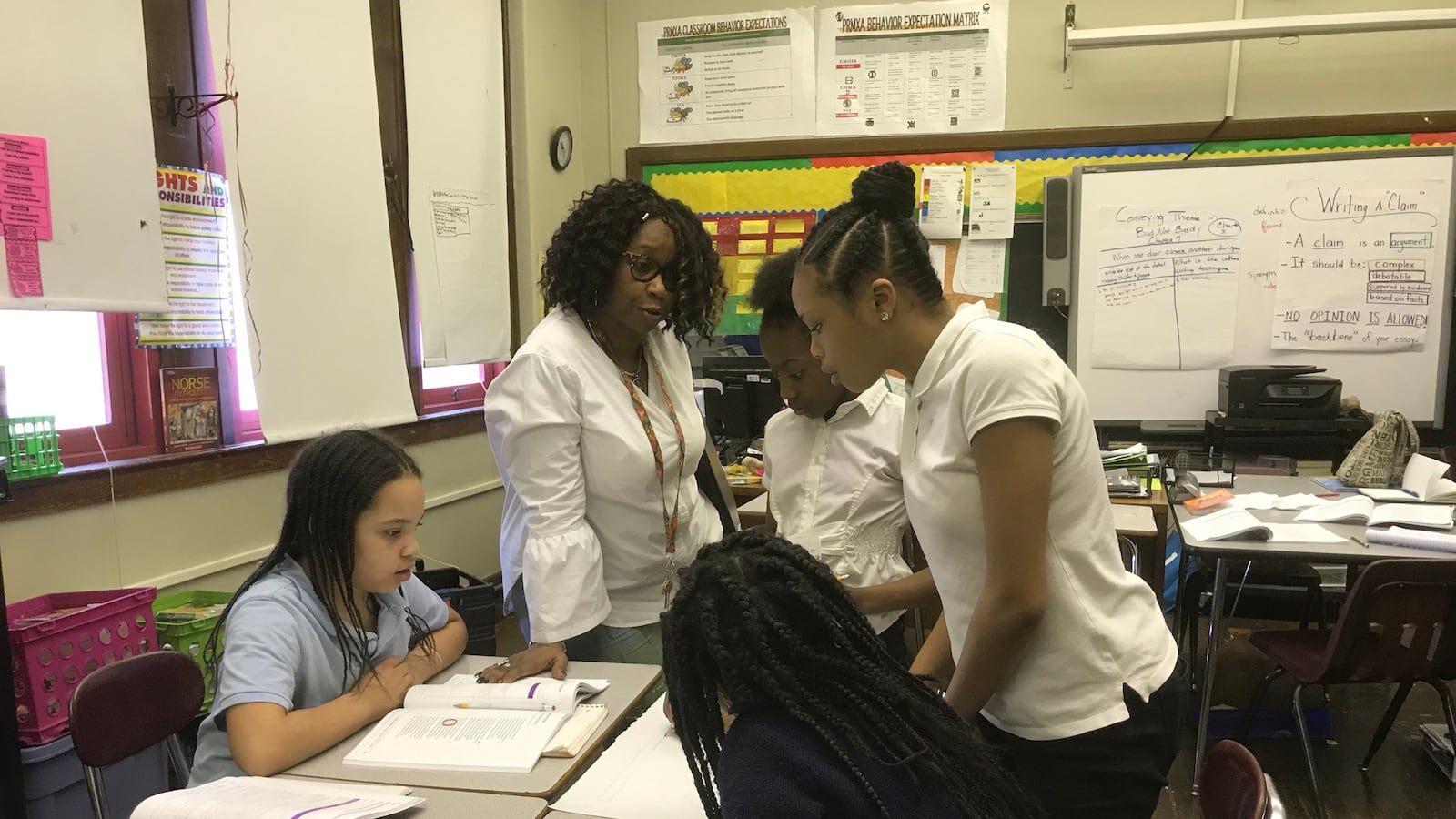

Dawson, the teacher at Paul Robeson Malcolm X, has taught in traditional school programs and African-centered programs. She prefers the latter because the approach promotes close connections between students and teachers.

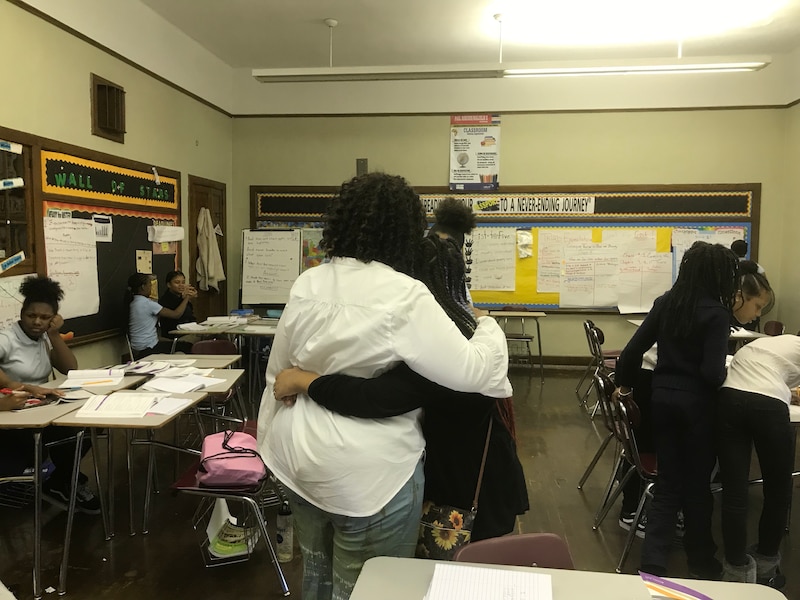

Teachers are referred to as “Mama” or “Baba” — African terms for mother and father. And like some mothers, Dawson is a tough disciplinarian in the classroom. But it’s also clear she knows her students well. As she was providing directions for an upcoming assignment with the girls in her English language arts class, she noticed one girl looked upset.

“The look on her face, her eyes, I knew something wasn’t quite right,” Dawson said. So she stopped in her tracks, and addressed the issue. The girl eventually left the classroom to see a counselor, but came back minutes later with a different attitude — beaming brightly later in the class when she was the first student to figure out the answer to a question that had stumped the rest of the girls in her class.

“You are given an opportunity to be more than a teacher,” Dawson said. “You are given the opportunity to let children see you as a person. You get to know them, you get to know their family. Any teacher can do that. But that’s what’s practiced at our school. That’s what’s expected at our school.”

When Dawson was talking to the boys about perseverance, she kept hammering home the importance of perseverance. She then related it back to a speech they had recently read in class, in which the speaker urged them to question how they would be remembered, to be the best they can be, and to not accept being average.

“For African American males, that’s a motto you need to get up in the morning saying to yourself,” Dawson said.