Detroit Superintendent Nikolai Vitti is entering what could arguably be considered his most critical year at the helm of the city school district — his third year that could see the emergence of solutions to mounting school facility problems.

During a lengthy interview earlier this month that covered a number of topics, Vitti hinted that business leaders have worked with the district to come up with a fix for the key question of how the district can fund facility improvements in its crumbling buildings. More details, he said, will be forthcoming.

Vitti also became emotional at times as he talked about his dream job as Detroit superintendent, the lessons he’s learned from past mistakes, and after the recorder had stopped, the childhood museum trips he took with his mother that made him want all Detroit children to have that kind of experience.

“For me to be here, with my history and at this moment, that’s special. No other district can provide that to me,” said Vitti, a Dearborn Heights native who came to Detroit after a five-year stint as superintendent in Jacksonville, Fla.

In his first two years, the district has adopted a new literacy and math curriculum, increased pay for teachers and other staff, cited data that shows decreased chronic absenteeism, and shown improvement on internal exams.

But there are challenges. The district has posted the worst results among big-city schools on a rigorous national exam. As many as 800 students in the district could be held back under the state’s third-grade reading law, which requires retention for children who are a grade level or more behind in reading. Facilities, too, are an issue.

Last year, a review of buildings found the district has $500 million in facility needs. And while a small amount of those needs are being taken care of using reserve funding, a larger solution is needed.

The district will begin holding community meetings in October to hear from residents, input that will go into deciding on a formal plan.

School closings are likely on the horizon, but Vitti said the district will take a different approach and is committed to phasing out schools rather than abruptly closing them.

“We’re not going to replicate the sins of the past.”

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

What will make year three successful?

I think we are where we should be going into year three. We’re starting to see districtwide improvement on attendance, reduction in chronic absenteeism, we’re seeing overall districtwide improvement in literacy and math. Then, if you drill down to individual schools, you’re seeing some double-digit improvement at individual schools in isolation. Really, that’s what we wanted and expected to see after year two.

After year three, I think we should see more schools with those bigger increases. Year three moves more to the high school level for reform, where we’ll see new curriculum for literacy and math, we’ll see a sharper focus on the SAT and becoming more specific on students being eligible for the Detroit Promise, (which provides college scholarships to eligible Detroit high school grads) defined by GPA and SAT, trying to increase the graduation rate. You’ll see the build out of the career academies at the high school.

And then, the big issue, aside from all of this… is to start [in October] to engage the community on the facility challenge. We’ll have a conversation about what did the facility review really say about the schools in that constellation. What is the need and what does enrollment look like? How many school age children are in that area. … Are we going to see an increase in school age kids in the next five-10 years, are we seeing a decrease, is it stagnant? How many kids are in charter schools in that area, and private schools? What’s the right kind of investment? Does it make sense to make a $30 million investment in a building, or does it make better sense to build a new building? Or to take three very old buildings and build a new building, where the three schools can be put together.

We would phase schools out and phase grade levels out rather than abruptly closing schools. But, part of this process has to be rightsizing the district. We have too many open seats. In that whole process we will always listen to and do right by the community. I want to be in a position and the board wants to be in a position to be authentic and transparent about our challenge. In the end we’re going to come up with a plan that keeps communities whole and is committed to traditional public education, where there is an accessible school within a two-mile radius across the board. We’re not going to replicate the sins of the past. People are going to know what the challenges are and they’re going to offer a solution because that’s our responsibility, but we’re not going to impose that solution without listening to people and people in that community saying, ok, we hear you, we understand this has to be done and there needs to be changes. What about this instead?

What are the solutions?

The engagement process is more about defining the problem and then coming up with the solutions that keep everyone whole, that protect traditional public education into the future. The back end financial solution, we’re still working on, but we’ve had a lot of support from the business community to analyze what our options are — from local taxation to a state solution. So, it has been encouraging to have a group of CEOs that have been committed to solving the problem.

That wasn’t the case a year ago. DTE especially has stepped up to help us problem-solve beyond what we’re able to do as a district because we’re limited in our resources and time. They have put some energy into analyzing the issue from a statute point of view and from a taxation point of view. So we’re not ready to announce yet what the solution is. But we’ve made inroads to look at financially what the options could be moving forward. I think it’s a combination of a local/state solution. I don’t think we can do it simply at the local level, and I don’t think we can expect the state to fix our problems, either. There has to be accountability and ownership for the legacy of disinvestment over the last decade. But at the same time, to be pragmatic, we also can’t expect the state to solve the problem, in and of itself, either. So I think we’re going to come up with a balance between the two.

Can the district seek a bond proposal?

We’re still analyzing it. But that’s what we’re exploring. What I can say is the initial thought was that we couldn’t do something but that’s what we’re exploring legally and I think there are some doors that are opening up to what DPSCD can do moving forward. A lot of that is tentative. We’re still exploring it. It’ll be something that we announce more formally when we feel we’ve crossed all the T’s and dotted all the I’s.

How confident are you that you can get buy-in from a community that has been opposed to closing schools?

What’s needed more than anything else is investment in current facilities. And I think that’s what people will see. In the past the majority of the conversation has been, this is what we’re taking away. And it was constantly taking away neighborhood schools, taking away legacy schools. That’s not what this conversation is about. The conversation is what is our plan to invest in infrastructure, to create sustainability and longevity, and at the same time, how do we rightsize the district in a logical, thoughtful way that even when that’s done, people don’t feel like you’re taking away? But it’s only logical to have to make difficult decisions at the same time when we have about 50,000 students in the school district, yet we have about 100,000 seats.

You’ve said the culture in the district is changing. How?

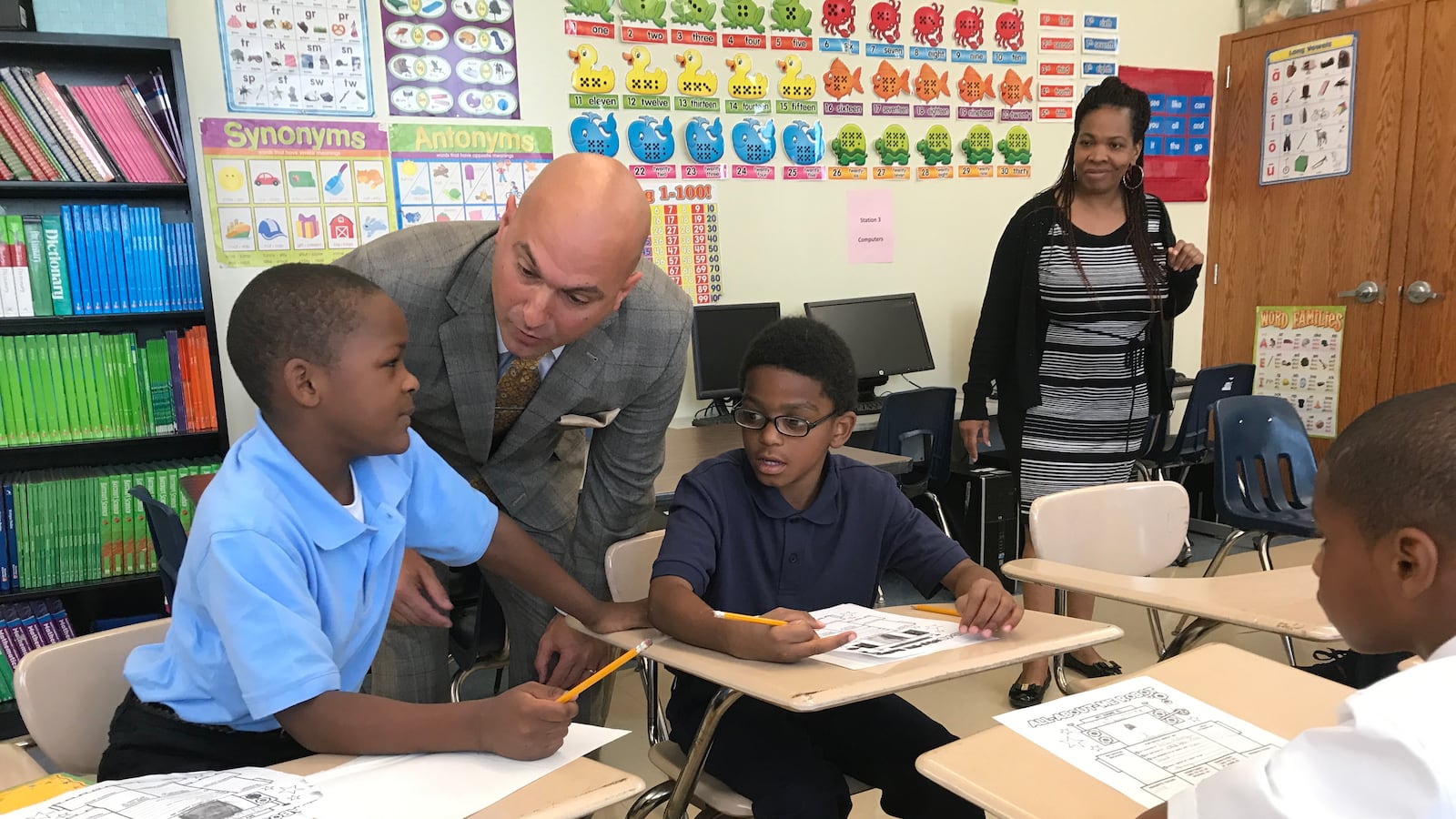

One, it’s just how principals talk about their schools. They’re focused more on what they’re doing and what they can do or what they’re going to do rather than being in a place of “I don’t,” “I can’t,” or “I don’t get this,” or “I don’t have that.” It’s not as much a resource conversation, it’s more about their intentionality and what they’re doing as a leader to improve their school. They’re more connected to teaching and learning than they were before. They’re in classrooms more. They’re more thoughtful about who are their stronger teachers, who are the weaker teachers. They’re talking more about how they use the master teacher to support teachers. They’re talking more about curriculum. They can talk to you more about how student performance looks across the board, what they’re doing about it. Those are all examples of the culture changing. Whereas before, it was more about just managing the day-to-day, rather than being visionary about where students would eventually go.

What would principals say is different about the kind of support they get from central office?

Probably, when you look at just how we’ve worked through the teacher contract collaboratively to recognize experience from outside Detroit, to offer the hard-to-assign bonus, to accelerate steps for social workers and psychologists. To just accelerate teacher salary, to create more school level positions like master teachers, deans, attendance agents. I just think they see a more active district, involved and supporting their work. I think those individuals would also say that district staff is more school-centric and more experienced in schools. So you have more people that are leading the district that have been principals, they have been teachers. So they know the work, they know the language. So those are the positives. The negatives would be just more involved, and that means more accountability, more oversight, more monitoring. There’s more investigations, there’s more follow-up and that’s because we’re more active. I think if you’re doing your job the right way and you’re comfortable with your body of work, then that’s not a threat, it’s just a reality.

How can the double digit increases in achievement you’ve seen at some schools be replicated?

A lot of it comes down to instructional leadership from the principal. The principals in those schools are deeply and authentically involved. They roll up their sleeves and problem-solve with teachers on implementation of the curriculum. They go to after-school sessions with the teachers to analyze the lessons. They’re in classrooms providing feedback. You’re facilitating teaching and learning conversations and then you’re empowering your teachers to see what they don’t see and work with each other on that as well. And faculties are buying into the work and owning it as well. That’s where you’re seeing the greatest improvement. These schools are for the most part fully staffed. And the minute you walk into the school you feel the culture and the energy and the purposefulness of what they’re doing.

You were surprised that some teachers weren’t teaching phonics. Does the new curriculum address that?

We’ve supplemented the K-2 curriculum with more foundational skills work. We started this summer with Orton-Gillingham training, which is a multisensory way to teach reading. I started to learn this based on my children being dyslexic and what it took to move them to being at grade level. We’ve got a long way to go, but at least we’re starting to build up that knowledge. In year three, year four, we’re going to have to start thinking differently about the schedule and time and what we’re doing, with students that are two or three grade levels below where they should be in reading. We’re not ready to do that at scale yet. I think this year has to be another year of just refining the curriculum, refining the intervention process within schools, the academic interventionists within small groups, moving forward with the high school curriculum.

But one area I think we’re going to start talking about at the end of year three, going into year four is how do we catch up those students who are two or more grade levels behind. We almost have 50% of our kids that are in that category. The traditional curriculum, and the traditional time, is not going to move those students to being at grade level. That’s the next phase of the challenge. So the Orton-Gillingham training is a step in the right direction, which is phonics focused. But it’s not just calling out letters and sounds. It’s a multisensory approach to do it where you’re connecting the left and the right hemispheres of the brain with the neurons that are not naturally connected. That’s why a lot of our students aren’t naturally reading because the synapses are not connected. So, by using a multisensory approach, that’s what connects the two. So you’re not just reading letter “A,” but you’re drawing it in sand, you’re using the multiple functions in your brain. We just have not taught our teachers to do that. It’s not their fault. But we’re going to start moving in that direction.

You’ve said you want to move the high schools to start later in the morning, which is a nod to research that shows early school-starts are harmful to teenagers.

The vision is to start later for high schools. We just have to work with our teachers to do that. I’m optimistic that it’ll be done. We just didn’t have the time to do it last year and I felt that if we did it, we would just create tension that would just distract us from doing the work. This year we’ll do more engaging of teachers to understand the rationale with starting later and how that would benefit students. There’s a way to do it, we just have to get people on board and understand the benefit from doing that.

I also think in the future we have to think differently about the [school year] calendar. I started that conversation last year. Starting earlier would be more beneficial, and having more professional development embedded in the school year would allow for greater training and impact. I also think we need to start thinking about summer and going longer and thinking differently about the calendar as a whole. So, not extending the year, but giving more breaks throughout the year, where you have two to three weeks off.

What will be important when the district begins negotiations at the end of the coming school year?

There’s so much to deal with, to problem-solve around. The challenge for us will be to renew the Wayne County millage (enhancement millage for schools). It’s going to be essential to sustain what we’re doing. If we lose $15 million in the budget, that has a big impact. We have negotiated in good faith and I think we have made compromises to focus on the reform and I have no reason to believe we’re not going to continue to do that. DFT knows and acknowledges that we have been problem- solving on behalf of teachers. And when we disagree, it’s really more about what can we afford right now to keep the district solvent. Nine out of 10 things, we agree on.

What would you say have been your biggest successes?

I’m really proud of the relationship I have with the board. Because it’s a strong relationship, it doesn’t get a lot of attention and that’s a good thing. A lot of people want conflict, and there isn’t sensationalism when people are actually working together, which is what kids deserve. But we work together and we trust each and we like each other. And for me that means a lot and it means a lot for this community, and it’s understated. And it’s undervalued. Because, if we start fighting we’re going to lose the reform and then it’s just a bunch of adults bickering with each other, where we lost sight of children. We don’t always agree. That’s the reality. But, we have put aside ego and delusions of grandeur and say we’re going to get this right for kids and for the district, and we’ve done a lot of important work in a short amount of time.

How about regrets?

I’ve been doing this for 15 years. I’ve learned a lot from the mistakes I’ve made in the past. I’ve said this countless times, and you have to really understand who I am to believe me when I say this [choking up]: I’m here for a reason. It was a long road, but a difficult one, personally and professionally for me to be the superintendent right here at this time. And I made a lot of mistakes getting up to this point. I think I’ve learned and reflected on those and been a better leader because of those. And I have a great board that has empowered me and trusted me, so that’s helped. Things I would do over? I think there are a couple personnel things that – people that I picked initially that weren’t the right fit but I think I cleaned that up. I would have redone some personnel decisions.

From a pure reflection point of view, there are moments when I went in deep on charter schools and that was purely authentic and that was me reacting to a place where the district didn’t have a voice and people didn’t have political space to be honest. And more people than not in the system supported what I said and felt like I spoke truth to what they felt for a long time, but it distracted people from what I’m trying to do. I will always speak out to what I think is wrong, especially when it comes to what I think is best for children, but there are moments when I have to create balance between that because then that’s what everyone is talking about and then all my time and energy gets shifted to that and that’s not going to change what’s happening to 50,000 students in the school district. I don’t apologize for what I said, but there are moments where I think the organization got distracted because I spoke out.

How confident do you feel in the complete turnaround of the district?

I have no doubt that it’s going to happen. What keeps me up at night, to answer that question with complete conviction, is the things that cannot be controlled with the process of reform. And that’s school board elections, who decides to run, who doesn’t. That’s the major factor. And then just the strength of the economy, how that influences K-12 funding. And, the political whims of the legislature. Those are factors that I can’t control.

Have you had moments where you regretted the decision to take on such a big job?

No. You can’t do this work with full authenticity and energy and commitment and not feel disappointed at moments because it’s not going fast enough, it’s not scaled enough, you don’t have the right resources and there’s just a ton of problems. So, if you’re honest and reflective, you have those moments of disappointment when you’re disappointed in yourself. But those are moments, not an overwhelming feeling.

I’ve always said that my dream job is to be chancellor of New York City. And I said that because it was the largest school district in the country. And I was just challenged by the greatest scale. I lived in New York. I worked in New York. Two of my kids were born in New York. But, that’s no longer my dream job. I don’t want another superintendency after this. And it’s not because I don’t want to be superintendent anymore. What could possibly be more fulfilling than being superintendent here? If and when we turn the district around, it’s always going to be the example of what could and should happen in urban school districts.

And any kind of dream has to have a personal side. So, that’s when I get sentimental [choking up]. For me to be here, with my history and at this moment, that’s special. I can look out the window and think of being here as a kid and hearing stories through my grandfather and my uncle and that’s who I am. Where am I going to get that? There’s no other place that can do that. When you grow up and you’re connected to a city and a history and the people and you’re a part of that, you can’t replicate that. The only way that I leave is if I’m forced out or if I don’t feel like the board is supporting the reform.