Amid a sharp decline in the number of Michigan school librarians, a new program was started this summer to use teachers to help fill those roles.

The Experimental School Library Media Specialist program allows already certified teachers to be recognized by the state as school librarians after they’ve taken just five additional classes, or 15 credits, at Wayne State University in Detroit.

The number of full-time certified librarians in Michigan has dropped sharply in recent years. Only 8 percent of schools have a librarian today; the figure has declined roughly 73 percent since 2000.

The number of people trained to be librarians has fallen sharply, too, so much so that librarians are on the state’s “critical shortage” list even as the number of available jobs shrinks.

The program’s website says impending retirements among the remaining librarians will open up jobs to new librarians.

The program was granted temporary permission from the Michigan Department of Education to allow teachers to add a new area of expertise in less time than usual. Teachers are typically required to take 20 credits in order to add a new area of expertise.

Programs like this one could find themselves in hot demand if three bills focused on school libraries become law this year. The bills would require every school in the state to have a library with a librarian, a process that could take years given the small number of people currently certified as librarians.

This is not the state’s only effort to combat educator shortages by reducing credentialing requirements. With districts in some areas struggling to hire teachers, lawmakers allowed for new teachers to lead classrooms after taking 300 hours of online classes.

Brian Peck, a spanish teacher at Osborn High School in Michigan, enrolled in the Wayne State program hoping to expand the library services offered at his school.

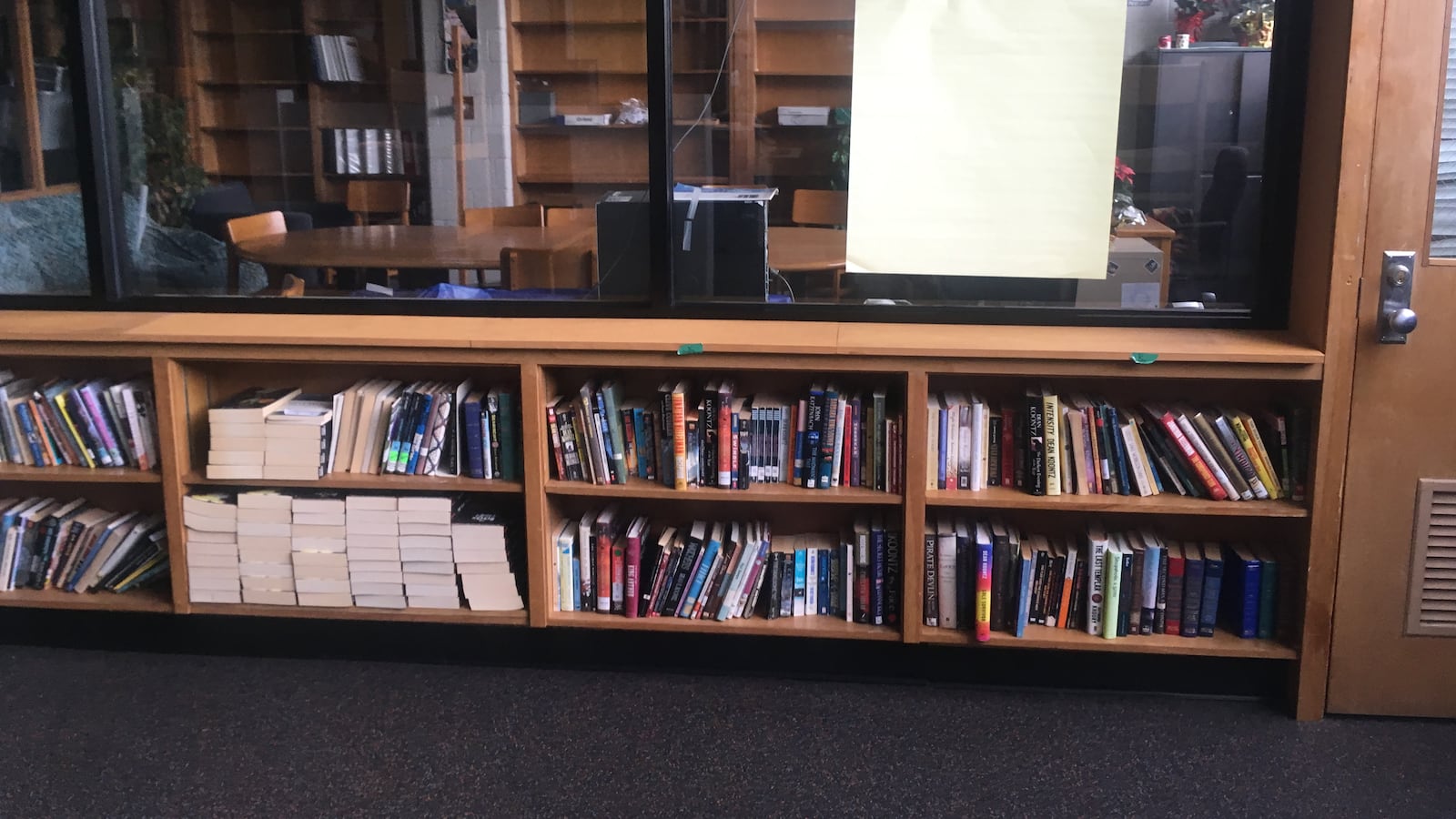

Three years ago, volunteers renovated his school library. But the new shelves were left empty, so teachers at the school asked the community to send books.

Donations flooded in, but Peck and other teachers, busy with their responsibilities, didn’t have time to organize them or sift out books that wouldn’t be useful. The school doesn’t have a librarian of any kind, state data shows.

Earlier this month — three years after the initial donations — Peck and a few volunteers finally got around to finishing up the task.

“One of the biggest problems I see with not having a librarian is that so many of our precious resources go unused or fall into disrepair because no one manages them,” he said.

He’d like to spend more time in the library — perhaps using the credential (he hasn’t yet completed the program) to work as a librarian for one hour a day — but he’s not sure the district can afford to give him a break from teaching.

“Until there’s more pressure on school districts to have librarians, I don’t think a lot of people in this program are going to have much success finding a job,” he said.