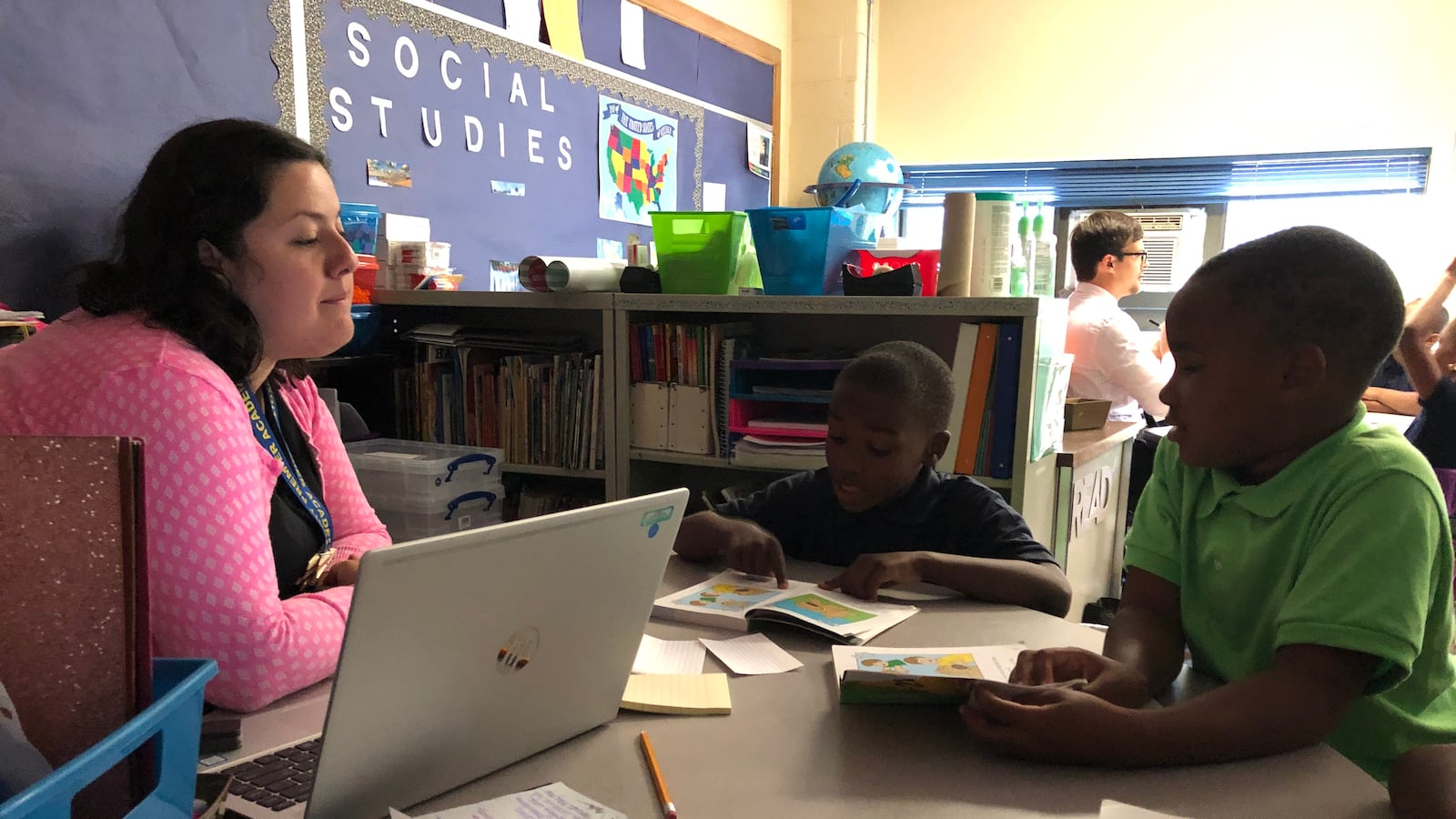

Three boys sat down around a table at Detroit Premier Academy and opened up their picture books. It was the beginning of the school year, and the race was on.

Their teacher, Whitney Vanatta, showed them an index card with the letters ‘Ck’ written on it.

“‘Ck’ says ‘kuh,’” she said.

“Kuh,” they echoed.

The lesson was designed to help the students learn the basic building blocks of English, sound by sound. It wouldn’t be out of place in any kindergarten classroom.

But these weren’t kindergartners — they were third-graders who were badly behind in reading.

They are far from alone. When Michigan’s controversial new “read or flunk” law goes into effect this year, as many as 5,000 third-graders who are reading on a second-grade level or below will be at risk of being held back.

With literacy at the center of a statewide debate, Chalkbeat is visiting classrooms to find out how educators are working to help struggling readers catch up.

The stakes go beyond simply repeating a grade: Poor readers are more likely to struggle in other subjects, drop out of high school, or end up in the criminal justice system.

Natalie Stephens, a dean at Premier Academy who oversees instruction in grades two through four, knows it.

“Sometimes it takes your breath away when you see the real numbers” of students who are behind, she said.

How is your school working to help struggling readers? Let us know.

While officials estimates suggest that 5% of students statewide could be held back under the new law, the effect is expected to be greater in schools, like Premier Academy, that enroll lots of students from low-income families.

Indeed, Stephens estimates that one in three third-graders at the school will score low enough this school year to be held back by the law. That would translate to 30 students being held back a grade — six times more than in a typical year.

Yet the school has built a track record of helping students improve their English skills faster than average. While only a handful are considered proficient, they have shown more improvement on state English exams in recent years than similar students elsewhere in the state.

The secret is obvious as soon as you walk into Room 204.

The classroom is staffed by four adults — three certified teachers and one aide. To teach reading, Premier Academy divides its students into three skill levels. This is the room for struggling readers.

Across the hall, more advanced students listened to their teacher read a story with words like “thesaurus” and “prehistoric.” Students in the in-between classroom worked on slightly easier texts.

In the room for struggling readers, teachers worked with a few students at a time, giving them mini-lessons matched to their reading ability. Those who were closer to a second-grade level, for instance, were asked to read comic books, sounding out words like “maybe” and memorizing words that don’t look like they sound.

A chime rang every 10 minutes or so, signaling that students should move on to another teacher or to a desk where they would quietly read books matched to their reading level. If students kept moving, the thinking went, they’d have less time to become frustrated if they got stuck on a lesson.

A few days after the school year started, Premier Academy enrolled a third-grader who hadn’t yet learned the alphabet beyond the letter “x.” A classroom designed specifically for new readers like him helps ensure that he won’t be asked to read texts he isn’t ready for, Stephens said.

“He would definitely be frustrated with instruction on grade level,” she said.

The idea that students should learn at their skill level instead of their grade level is hotly debated among education researchers. As the Detroit Public Schools Community District adopts its new curriculum, it is giving students on-grade-level material even if it is difficult for them.

Tim Shanahan, a literacy expert and emeritus professor at the University of Illinois, has built his career in part on the argument that students should always be given age-appropriate materials, even if they’ve fallen behind. But he said the arrangement at Premier Academy made sense.

“If kids are just beginning to learn to read, it may make no sense to put them in their grade level texts,” he said.

Paying extra attention to individual struggling readers is the best way to help them improve, said Robert Slavin, a professor of education at Johns Hopkins University. He opposes retention in general, and said a hands-on approach like the one at Premier Academy would do students more good than holding them back.

“Each and every one of the struggling readers should be getting one-on-one tutoring, he said. “Getting even one teacher to a small group of students is a big victory.”

Different versions of that approach are gaining traction across Michigan. The Detroit district, for example, is recruiting and training volunteers to work with students on reading during the school day.

Amanda Bauer, principal at Premier Academy, said she expected students in this classroom to gain more than one grade level per year. If that happens, she said she would hesitate to hold them back.

“If they work diligently to show growth each year, we want to take that seriously,” she said, adding: “The last thing we want is to promote them just to promote them.”

Discipline, attendance, state law, parents’ opinions, and student growth are some of the factors Premier Academy considers before holding students back, she said.

Thanks to provisions in the law that exempt some students from the law, Bauer guessed that the school will hold back about the same number of third-graders this year as last year, when the law wasn’t in effect.