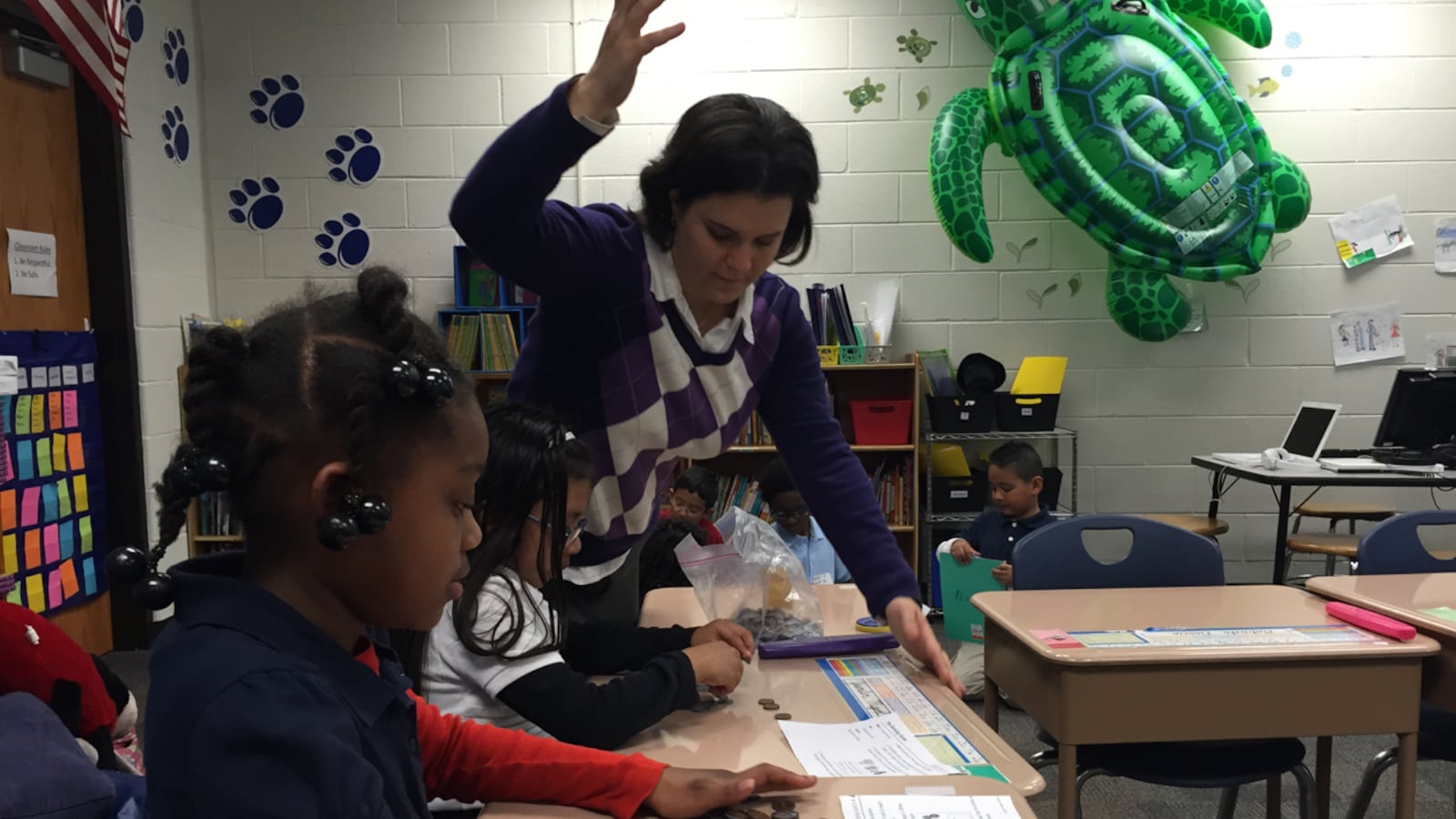

During an hour-long math lesson, Shana Nissenbaum hardly ever stands still.

One minute, she sat at a row of desks checking the work of two of her third-graders as they practiced counting fake coins. The next, she wedged herself under a table to sit with a boy struggling to measure the perimeter of shapes. Another group took a “divide and conquer” approach to their task — one student lined up paper clips on the cardboard shapes while another wrote down the answers.

What she wasn’t doing much was standing in front of the class teaching all her students in her Key Learning Community School third grade class the same thing at once.

Nissenbaum’s not alone. Fewer lectures is one way Indianapolis Public Schools’ teachers are adapting to the state’s new academic standards, which went into effect in July after Indiana’s quick about-face and rejection of Common Core standards earlier this year.

Grouping students by ability level is intended to help them focus on the skills they need to master and can be especially helpful to those who are well ahead of their classmates, or far behind, Nissenbaum, 32, said.

“As much as possible, I do group work,” she said. “That really meets individual needs.”

She cited an English standard in reading — which asks that students be proficient at finding the main idea of a passage — as a hypothetical example of how lecture doesn’t work for some kids, particularly those who have already grasped the concept.

“Frankie doesn’t need to hear about the main idea, so why am I spending my time and resources on him to continue speaking about it when someone else in the class doesn’t understand it yet?” Nissenbaum said.

Indiana’s new academic standards are a set of expectations for what students should learn at each grade. The new ones the state adopted in April aim to require teachers to be more attentive than ever to exactly what each student does and doesn’t know.

But teachers are still dealing with the same limited time and resources. Doing more group work, and more detailed tracking of what students learn, is one way the district is attempting to manage those new demands, which also include newly redesigned ISTEP tests come spring.

Tammy Bowman, the IPS’ head curriculum officer, said staff training that started in September focused on those areas — helping teachers get away from lecture and having them make sure students master the content and skills in every new standard before moving on to other topics.

“I used to tell my students that ‘kid language’ can be so much more powerful than me sometimes, because you know what that other student needs to hear because you think just like them,” Bowman said.

More group work and emphasizing mastery are considered best practice for teachers, she said, but the district focused on them intentionally to support teachers in the transition to new standards and help align with the new administration’s goals for IPS.

“We feel pretty good about the buy-in,” Bowman said. “Because for some people, these are major changes in philosophy and thinking … I think we are making really good progress.”

New standards, new strategies

Common Core is a set of new learning standards that Indiana, like 45 other states and the District of Columbia, agreed to follow with a goal of boosting students’ academic skills. Indiana was an early adopter of Common Core in 2010.

Then-Gov. Mitch Mitch Daniels and then-state Superintendent Tony Bennett both backed Common Core and the standards were instituted with little fanfare. But once President Obama and the U.S. Department of Education began encouraging states to follow Common Core, parents and legislators began to question if they made sense for every state.

Indiana critics argued the state should just write its own standards, as it had been doing before Common Core entered the picture. After a bill ordered just that earlier this year, by voiding Indiana’s Common Core adoption, new Gov. Mike Pence and new state Superintendent Glenda Ritz jointly endorsed standards produced in February by panels of educators and experts.

But the new Indiana-specific standards didn’t satisfy everyone. Critics who argued against Common Core said they were too similar to Common Core. Those who wanted to keep Common Core said the new standards took out some of the elements that they believed would help make Common Core effective, like specific guidance to help teachers interpret them.

Others complained the standards were adopted too late, giving teachers and schools just a few months to get ready to teach them to students. With ISTEP tests also being rewritten to reflect the new standards, teachers have to create new lessons without knowing what those tests will look like.

Since the start of the school year, teachers across Marion County have been working to make changes to how they teach so their students will cover everything they need to learn before they take ISTEP later in the school year.

For the Key school, the change disrupted a methodical system of planning lessons, where the school’s tests are written based on standards, with daily lessons and activities created after the tests are made. But Nissenbaum said working at the school and learning ways to become more efficient and organized have made her a “1,000 percent better teacher.”

Adapting to a new reality

Nissenbaum spent her time after college moving around to schools in Pennsylvania and New York before accepting a temporary position at IPS School 44. Key, which serves grades K to 12, was overhauled three years ago after years of struggles. Its high school, for example, had earned D and F grades for low test scores for more than half a decade. Nissenbaum interviewed for a job with new Principal Sheila Dollaske in 2011. She was excited by Dollaske’s vision for the school.

“It just sounded like a different environment for students,” Nissenbaum said. “And I was like, ‘I want to be a part of that, so let’s see,’ and that was it. I fell in love with it.”

Like others at the school, Nissenbaum keeps meticulous data on her students’ achievement and what standards they have mastered so she knows exactly how to plan her lessons and instruction for each unit. It also gives teachers a chance to catch students before they fall too far behind, Bowman said, since they know along the way what areas might be more challenging to each child.

“Yes, it’s a lot more work,” Nissenbaum said, “Especially the way we do it. But the payoff is bigger. If it’s done right, I can tell you which of my kids understands each of these standards, and to what degree and how to help them.”

As principal, Dollaske thinks of herself as one of those assembly-line machines that dispenses candy into packages in exact amounts: She tries to give everyone enough information to do their jobs, but not so much that they are overloaded. With a barrage of presentations, guidelines and ISTEP materials coming from the Indiana Department of Education every few weeks, that can be a struggle.

But Dollaske came to Key for that sort of challenge. After training principals in Chicago, she was enticed to Key by the challenge of trying to make the schools’ famous curriculum — based on the theory of Multiple Intelligences — succeed in the state’s accountability system. This is her third year, but next year could be the end for Key. The school board are considering the possibility of closing the school and discontinuing its first-of-a-kind program in 2016.

Dollaske and her staff are trying to stay focused on helping students achieve, including passing ISTEP. Recently released sample questions for the new ISTEP have helped, she said.

“We tend to not sit back and wait,” Dollaske said. “And so now that we have an idea of what anchor assessment items look like, we’re breaking those down and seeing what the standards look like in action … standards are really hard to teach without knowing what the test will look like.”

Key teachers and staff only began going through the sample questions last month. Nissenbaum is unhappy with a lot of what the education department has said so far about the new test, which will include new questions that ask kids to show how to solve a problem, not just get the right answer, using a computer.

Much of her frustration is in the lack of specifics: New practice tests are for combined grades 3 and 4, 5 and 6, and 7 and 8. How do teachers know which problems are for which grades, she asked? Why are the directions for some problems split up and put in different fonts?

“This is a disastrous pile of stuff on this page for you,” she said. “I look at this, and I don’t even know where to start, and I’m a good reader.”

Before they can focus on content, Dollaske said, they need to help kids learn computer skills they may not have.

It’s as if, she said, “I went in to take my drivers test and all of a sudden they asked me to say how I’d drive on a motorcycle. I’d still know the rules, the laws, but I haven’t done it on a motorcycle. That’s how we are going to try to approach the technology side.”

Keeping kids from falling behind

When School 61 second grade teacher Natalie Merz announced to her class that they’d be doing a “scoot” activity during math, one kid jumped to his feet, pumping his fist with joy.

“Take a few minutes at each problem and scoot to the next one,” Merz explained to her charges.

Because her kids don’t take ISTEP, Merz would seem to be free from some pressures of preparing them for standardized exams. But she’s already thinking about the tests her students will take next year.

By third grade, her students will be expected to be proficient readers, but teachers can’t always expect that all their students are performing at grade level. She has to know what each kids needs to learn to be ready for next year and let them work at their own paces to meet that standard.

So her children often tackle tasks with varying degrees of difficulty, such as the “scoot” activity.

“Teaching is just literally, what does this kid need?” said Merz. “It’s finding 26 different ways to do something.”

On a recent morning, her class was practicing double-digit addition and subtraction. The kids sat cross-legged on the floor or sprawled out alongside bookshelves as they grabbed the cards got to work on math problems printed on the front side.

“Remember, in third grade we’ve got to show our work,” Merz said.

This is Merz’s second year with this class and her first year teaching second grade. She previously taught first grade and began her career as a Teach for America fellow in 2009. She’s been active with Teach Plus, a national a national group that aims to get teachers involved in advocacy and policy work. She’s known she wanted to be a teacher since middle school.

“I kind of got into what felt natural,” she said. “By the time I went to college, I just loved it.”

Even in her short career, she’s seen a lot of changes. Indiana is now on its third set of academic standards in her five years in the classroom. Perhaps that’s why Merz feels like it gets easier to adapt to the new standards each day. She’s optimistic next year, it will be even smoother.

That is, as long as the standards don’t change again.

“The big thing is I’m glad we’ve finally picked something,” Merz said. “We just want to teach kids what they need to learn and get them ready for life, not just the test.”