If someone is going to overhaul Indianapolis Public Schools on the city’s Near Eastside, community members want to own the reinvention.

At School 15, some neighbors are nervous they could lose a say in the school. IPS is ramping up its innovation plan — which so far has meant bringing in charter schools to try to turn around some of the city’s lowest scoring schools. And with persistently low test scores and four straight years of D and F grades from the state, School 15 could soon face big changes.

But instead of resisting, neighborhood leaders are asking for a voice in creating a plan to transform School 15 and other struggling schools nearby.

“If we really want neighborhood schools, we need to do it,” said Mike Bowling, a pastor at the Englewood Christian Church.

If the district ultimately goes along with community proposals, it could lead to neighborhood-led innovation schools — still part of IPS, but with more freedom and less central office oversight.

In pursuit of that goal, the neighborhood has created as steering committee to work on school issues, which includes members from the John Boner Neighborhood Centers, Englewood Community Development Corporation, Near East Area Renewal, Local Initiatives Support Corporation and Englewood Christian Church.

“We think we have everything we need here to make this a successful school,” said Susan Adams, a member of the steering committee and a former IPS teacher. “It should belong to the neighborhood, and we think it will be a great school when it actually does belong to the neighborhood.”

Community planning

For now, organizers are looking to parents, teachers and neighbors for input on whether to pursue neighborhood-led innovation schools and what those schools should look like. There is no timeline for when the potential school relaunch might occur

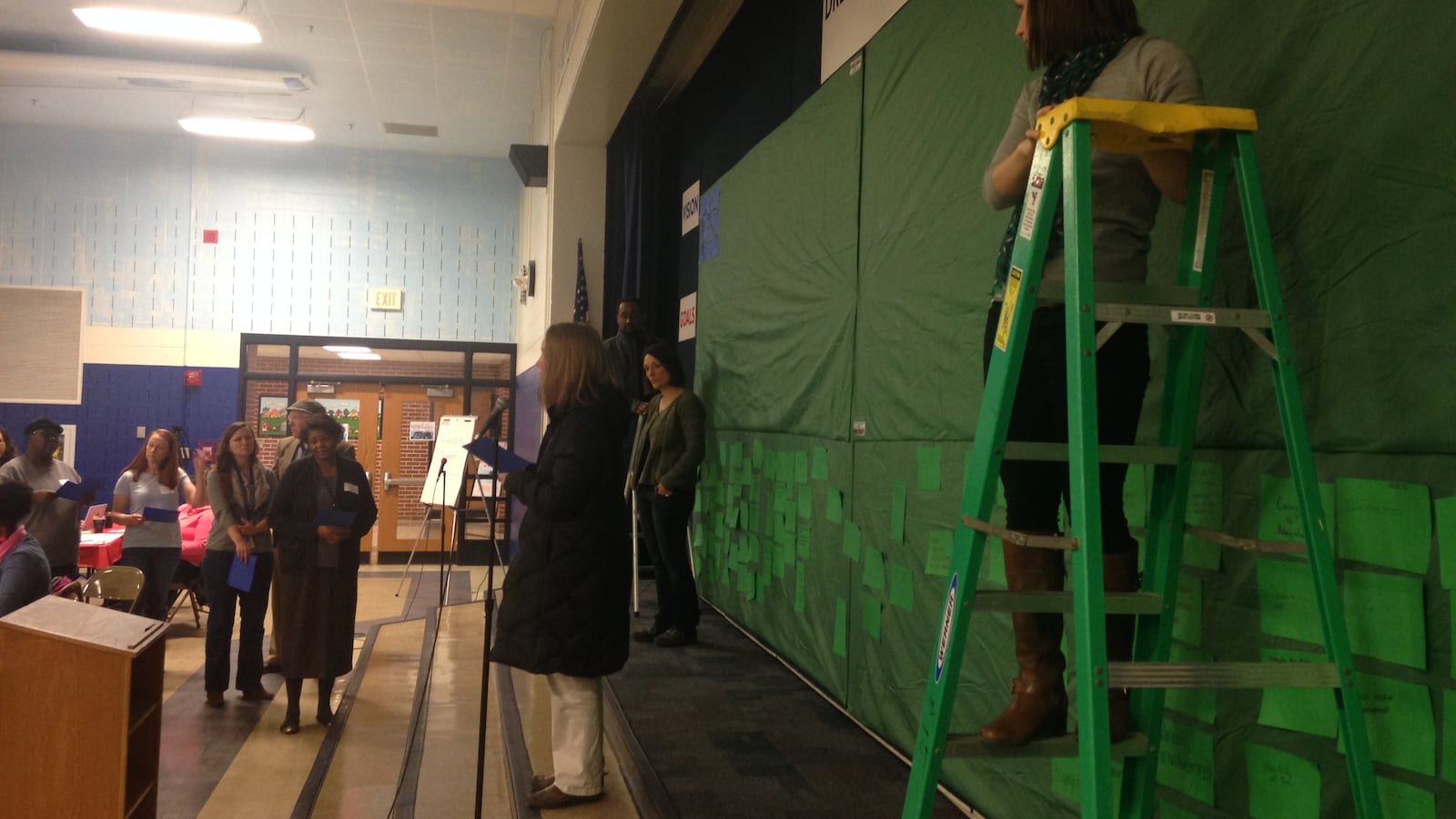

At their first public meeting Saturday, about 250 people crowded into the School 15 cafeteria. They sat around tables, brainstorming ideas for what schools should offer and how they could better serve their students and community.

“Before we even wanted to put pen to paper … we said, we’ve got to convene neighbors,” said James Taylor, the CEO of the Boner Neighborhood Centers. “This is our community saying this is what we want for our neighborhood.”

There were lots of ideas tossed around. But some common priorities were widely shared: smaller class sizes, less teacher turnover and more enrichment.

Just the idea of local schools creating new opportunities for parents and neighbors to get involved was met with enthusiasm.

“I think it’s great,” said Shiwanda Brown, whose daughter is in 6th grade at School 15. “The school is in the community and they want it to be nice and decent. … The community can help with the school.”

Teachers at School 15 are also eager to have a voice in its rebirth. Debra Barlowe, a sixth-grade reading teacher, said the best people to improve a school are those who are already invested in it.

“Before you bring in outsiders,” she said, “at least give the community in which the school is located an opportunity to build upon what’s theirs.”

Hub of the neighborhood

At the center of the committee’s vision for a locally managed innovation school is a vibrant, successful neighborhood school that can also serve as a key hub of the community.

School 15 has many students who face barriers to learning. About 87 percent of students qualify for free and reduced price lunch, which means their families earn less than $43,500 annually, and 35 percent of students were English language learners last year. Data on the number of students learning English this year is not yet available from the state.

When families need services, school staff may refer them to the Boner Neighborhood Centers, Taylor said. But although Boner has a center is just a few minutes away, many families don’t make it there, he said.

One idea for a community-run innovation school would be embedding those services at the school, Taylor said.

Neighbors have to insist on having a role in the school so that they can help children and families that are facing challenges at home, Bowling said. Thinking of the school as a separate entity is backward.

“We want this to be a community center that does high-quality elementary education,” he said.

Choosing to leave

The neighborhood around School 15 is racially and economically diverse, leaders said. In recent years, revitalization efforts have transformed houses and brought in waves of new residents.

But many people who have moved into the new houses in the area don’t send their children to neighborhood schools, Taylor said.

“Right now, a lot of the more affluent families are sending their children out of the neighborhood because they understand how the system works,” said Adams, who lives in the area.

In a district where school choice is thriving and families can send their children to public magnet, charter and innovation schools across the city, attracting families back to School 15 will be challenging.

But leaders believe that if the community invests in local innovation schools, the schools can draw in families.

“If we had a school that represented the whole economic diversity of the neighborhood, the racial diversity of the neighborhood,” Adams said, “we would have a school that’s rich.”

An unusual innovation

Politicians and district leaders have floated the possibility of a community-managed innovation school since the state legislature authorized IPS to partner with outside organization in 2014. But so far there hasn’t been an example of a school transformation led by parents and community leaders. Innovation school reform plans have come from the district.

As it stands, School 103 is the only traditional public school that the district has converted to an innovation school. It’s now managed by Phalen Leadership Academy, a local charter network. But that seems likely to change. School 93 and Cold Spring School are interested in converting to innovation schools next year, and IPS is on the cusp of partnering with local charter schools to run two persistently failing schools, School 69 and School 44.

(Read more: Two struggling IPS schools could be ‘restarted’ next year.)

In order to launch an innovation school, the neighborhood would need to form a non-profit organization and gain approval from the IPS School Board. Although the plan is in its infancy, the district has been supportive so far, leaders said.

Board member Michael O’Connor, who represents the neighborhood, and Superintendent Lewis Ferebee both attended the meeting at School 15.

“I’m just really thrilled and inspired that we have so many people who are interested and who want to come to the table and share their thoughts and ideas,” Ferebee said. “This is what we envisioned … for innovation. It would start with conversations like the one today.”