After three years as a teacher, Britney Yount realized that if she wanted a leadership role in education, she would have to leave the classroom.

So Yount took a job as an instructional coach for Teach for America, and now she spends her days training other teachers. But she’d like to be teaching kids, too.

“Every time I go in a classroom and I see kids with their teacher and they’re not my kids, I really, really miss that,” she said. “But I really want to use the skills I’ve learned in the last couple of years.”

It’s a common problem in education: in order for less experienced teachers to benefit from the knowledge of their peers, educators who use their expertise to offer training or support often have to give up teaching. That means kids are missing out on learning from some of the very best teachers.

A new program in Indianapolis Public Schools aims to change that equation by giving educators the chance to be professional leaders and mentors without leaving the classroom. The program will offer a small group of teachers with records of success extra pay to lead other teachers or teach more students.

The district is offering big money for the teachers it selects. They can make as much as $18,300 in extra pay, depending on how many extra duties they take on. All the teachers in the program will make at least $6,800 in extra pay.

Yount, who was at an informational meeting on the new program last week, was enthusiastic.

“I’m here to figure out a way to be in a classroom and have a community of kiddos that are mine, but also increase my leadership skills,” she said.

The “opportunity culture” initiative, which is modeled on a program developed in North Carolina, will pilot at six IPS schools beginning next fall. Each school is structuring its new leadership roles differently, but they fall into two categories — positions where teachers will educate more students than usual and positions where they will lead and coach other teachers in their school.

The goal is for excellent teachers to have an even greater effect on their schools, said Mindy Schlegel, the district’s talent officer.

“The thing that’s typically been done in education is that we pull our best people out to be coaches,” she said. “They’re no longer in front of kids or accountable for student outcomes.”

Struggling schools lead the charge

The six schools trying out the program are facing big challenges. They all struggle with low student test scores, and they are all part of “transformation zones,” an IPS turnaround effort that launched this year.

Those schools are a good fit for the program precisely because they need to attract and retain talented teachers, and they need strong teacher leadership, Schlegel said.

“We need something different,” said Crishell Sam, principal of School 48, a transformation zone school that will be in the pilot group. “We need something new because you can’t keep operating and doing the same thing in order to get different results.”

The other schools that will pilot opportunity culture include three elementary schools and two secondary schools: School 107, School 63, School 49, Northwest High School and George Washington High School.

Some of the schools will hire teachers to lead teams of other educators, taking on responsibilities like lesson planning and coaching. But they will still rotate into the classroom, working directly with students. Other schools will use strategies like team teaching and blended learning to help excellent teachers reach more students.

If the pilot program is successful, the district plans to slowly roll it out to more schools, Schlegel said.

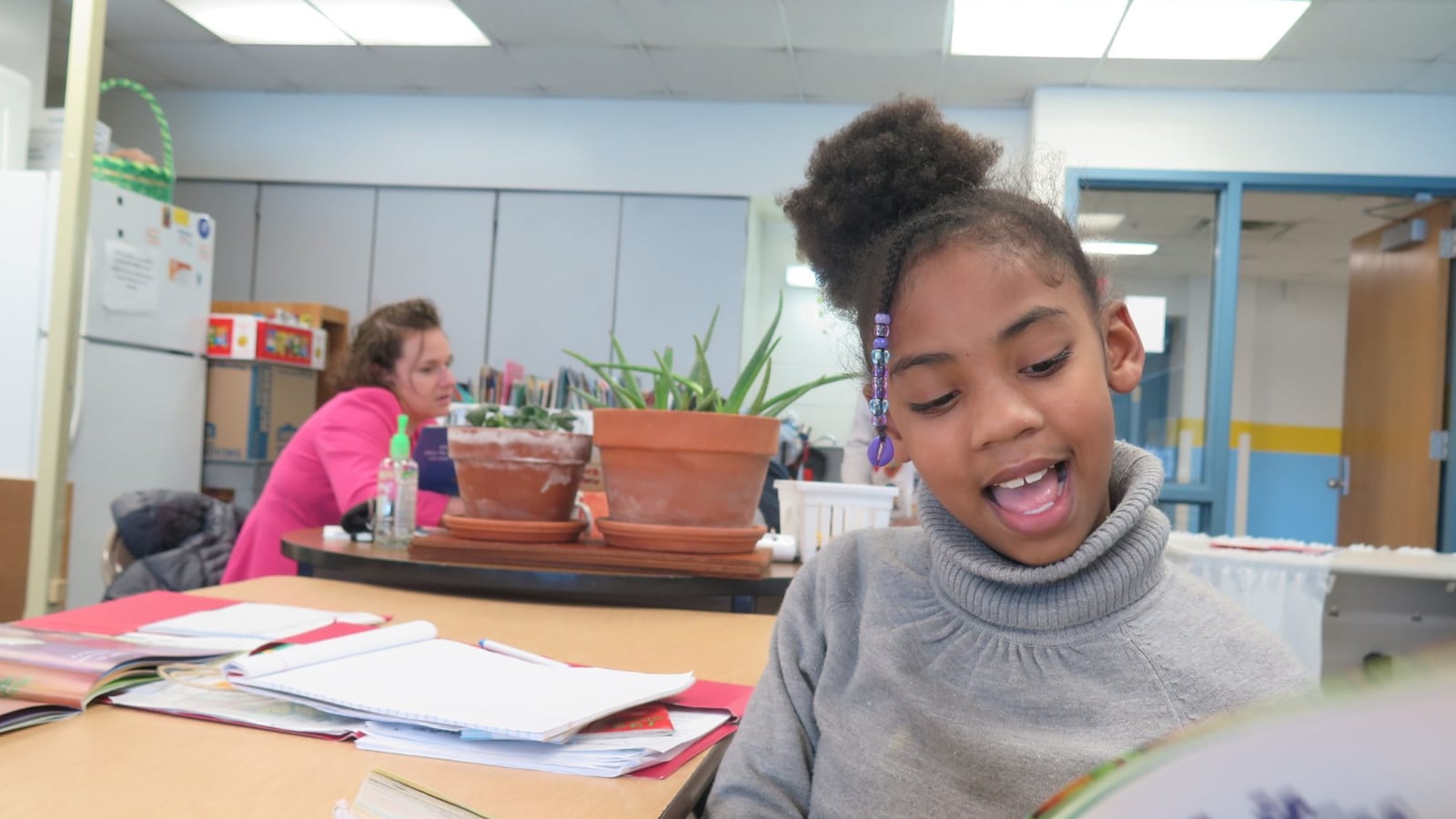

School 48 is starting small with just one teacher in the program. In order to help third-grade students improve their reading, Sam plans to hire a teacher who will be dedicated to literacy. The teacher will only teach reading and writing, while other educators teach subjects such as math and science.

Elementary school teachers often have subjects that they love to teach and plan for. With opportunity culture, Sam said, “that one teacher who has all of these ideas and ways in which to make it work, she has that opportunity to expand her reach with those students.”

Balancing the costs

There’s no extra money on the table to help schools pay the teacher leaders they recruit. Instead, principals must shift funding from other parts of their budgets to pay for the leaders they want.

Teachers in leadership roles will earn additional stipends that won’t be less than $6,800 extra. But some teachers could earn up to $18,300 per year from the stipend, if they are leading several other teachers. The cost to schools will depend on how many teachers they select for leadership and what type of positions they decide to offer.

No current staff will lose their jobs to pay for stipends, Schlegel said. But principals may decide not to fill open positions.

There’s an advantage to building the program into school budgets, Schlegel said, because it will make it more sustainable in the long-term. Unlike prior, grant-funded initiatives to improve teacher leadership, the money won’t disappear.

“What we’re really looking to do,” she said, “is to start to think about building teacher leadership positions that can exist permanently.”