One Indiana teaching college is responding to teacher shortages by transforming the way its teachers are trained.

With some school districts across the state reporting difficulty hiring and retaining teachers, particularly in rural and urban areas, Marian University’s Educators College is introducing a plan to recruit more diverse, accomplished teaching candidates — and make sure they have the tools to not just enter the classroom, but make a career there.

Central to the effort are new rules that — starting next year — will require Marian students pursuing a traditional teaching license to spend a year in a classroom working closely with an experienced “master” teacher as part of a one-year residency program before getting a classroom of their own.

“We’re really preparing them to be effective teachers during their first year under the guidance of a master teacher,” said new Educators College Dean Ken Britt. “It’s not just doing the same thing over a longer period of time. We really have to (create) these residencies in a way that they’re working under the best teachers in the district.”

Read: The basics of Indiana’s teacher shortage debate: What comes next?

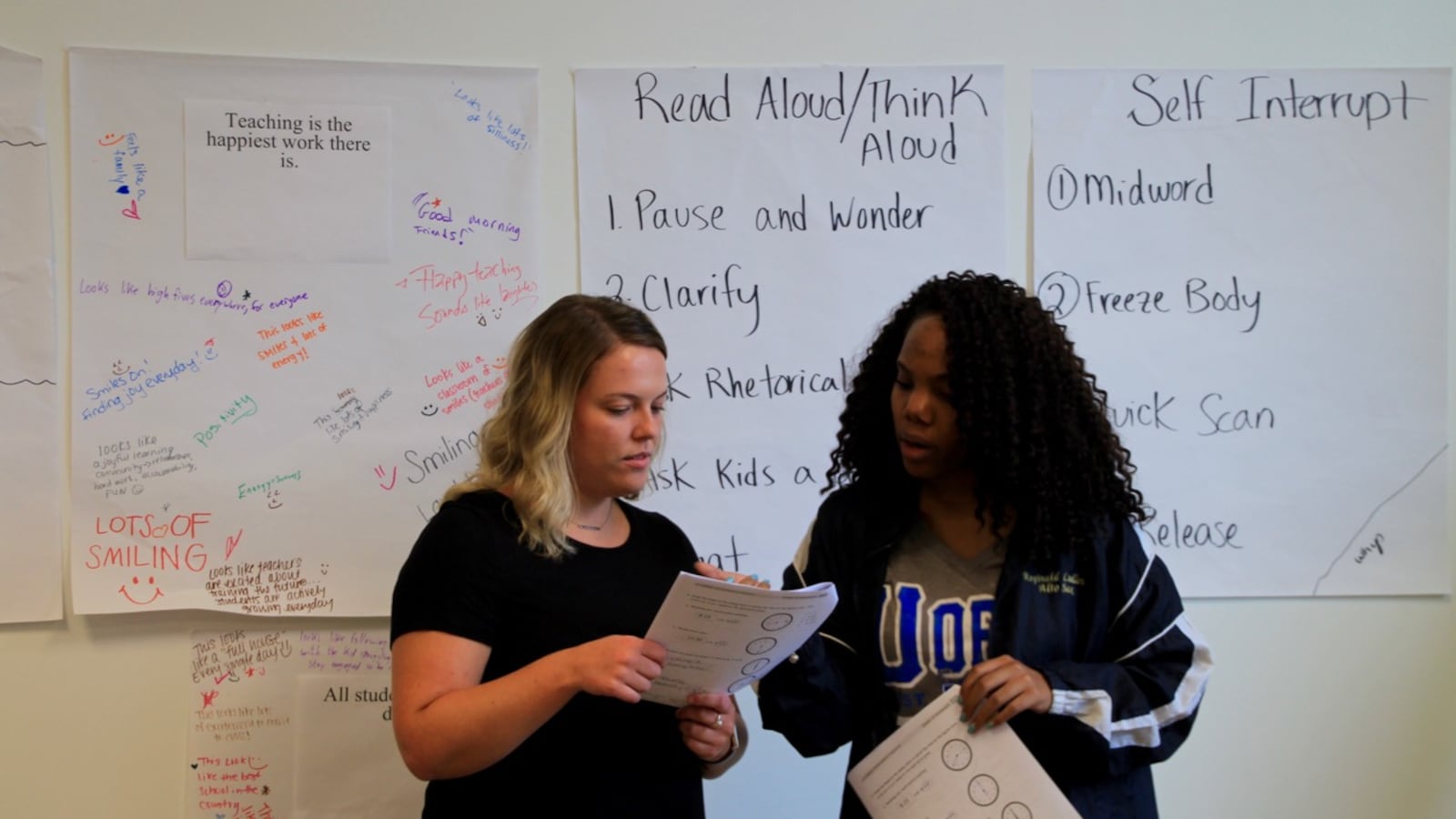

The new program is inspired by the best teacher prep programs in the world including those in Finland and Japan, Britt said. In those countries, teachers don’t just learn the theory of teaching, they spend time working on their craft with other teachers throughout their education.

That’s in contrast to the United States where many states, including Indiana, generally require that teachers be “certified,” but there are few standard definitions nationwide for what certification must entail. With teacher quality often cited as crucial to student success — and teacher shortages a problem plaguing school districts across the nation — some teaching colleges are re-examining the way they train educators.

When Marian rolls out its new program next year, students will no longer complete student teaching before graduation. Instead, they will finish their bachelor’s degrees and then embark on a teaching residency and master’s program, similar in some ways to how a medical school might work. That way, they’d have much more time to work with mentor teachers than current students, who might only spend a semester teaching before they graduate.

And the bachelor’s programs themselves will also see major changes. All students will be expected to learn strategies to teach kids how to read, for example, a skill that’s in high demand in many schools, Britt said. The college also plans to design majors that correlate with positions that consistently go unfilled across the state, such as jobs in special education, English-learning and high school sciences.

“Everything is dependent on the human capital that exists within schools,” Britt said. “That’s really the impact that we want to have. We want to fundamentally change the way we operate, particularly from the teacher prep standpoint.”

Britt said the advanced degree is especially necessary given potential changes to regional requirements for teaching courses that high school students take to earn college credit. As early as next year, unless Indiana is granted a waiver, educators who want to teach dual credit classes must have master’s degrees or 18 hours of graduate college credit in their subject.

Marian’s plan is also designed to to entice more high-achieving students to become teachers, especially students of color. To do that, the university intends to build more partnerships with community groups such as Indiana Black Expo and the Indianapolis Urban League to help increase efforts to enroll students of color.

“They are out there, we just have to find them,” Britt said.

Marian is still working out some of the specifics, such as how it plans to help students pay for the potentially longer degree programs. The school is also still considering how to fit the program in the shortest time possible, which might require students to study during the summer or enter college with a certain amount of Advanced Placement, International Baccalaureate or other college credits.

In seven years, the university hopes its new program can help the school double its teaching college to about 1,000 students and inspire other schools to take similar steps, Britt said.

“This was a wakeup call for us as a university to chart a new course for teacher formation,” Britt said. “Hopefully other schools of education in the city and state will follow.”