The ceiling of Principal Aleicha Ostler’s office in School 19 often vibrates, as small feet clamor and stomp above her head.

Ostler’s office isn’t below the gym or a busy hallway, but the classroom above her is seldom quiet. That’s because nearly every class at School 19 has physical activity built into the day, with students walking, dancing and stomping as they study English, math and history.

An elementary and middle school southeast of downtown, School 19 — known in Indianapolis as the SUPER school — is among the most popular magnet schools in the city. Then again, it’s a rare breed: a magnet program focused on health and physical activity at a time when some schools prohibit students from moving during class.

“Here it’s encouraged,” Ostler said. “When they are sitting on a yoga ball, they can rock, they can bounce. They are not told to stop.”

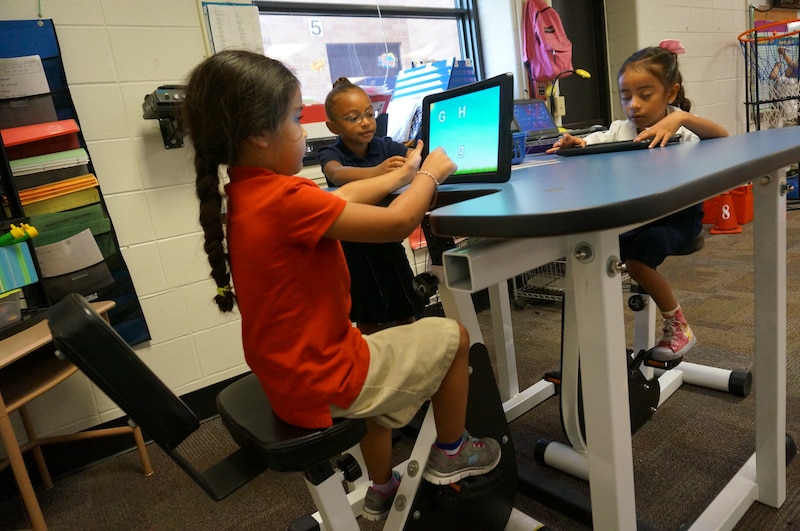

In addition to yoga balls in every classroom, the school has standing desks and exercise equipment students can use during class — such as pedals under desks, stools that spin and child-size ellipticals.

On a Monday afternoon, the students in one classroom chanted and stomped their feet to music as they counted by seven. Down the hall, seventh graders walked to each side of their social studies class for a debate about whether it’s a “big deal” when football players don’t stand for the national anthem.

In a kindergarten classroom, the teacher led his students in physical movements as they spelled out words, touching his hands to his head, waist and feet for each letter.

“They are just very simple strategies,” said Ostler, who has been principal of School 19 for eight years.

It’s an approach that has proven popular with families. The magnet program is open to children from across the district, and it commonly attracts more students than it can serve — particularly for middle school, which sometimes has more than 100 students on the waitlist, Ostler said.

Yet the little known program ignited controversy last month, when the IPS administration revealed a proposal to convert School 43 to a SUPER school without consulting community leaders. After receiving a rebuke from board member Kelly Bentley, the district retracted the plan. The future of School 43 is still undecided, however, and the school could still convert to a magnet with a health and physical activity focus.

If that happens, School 43’s leaders will be able to use the lessons that School 19 learned as it ramped up its fitness focus. The school added fitness courses on a trial basis after a district official suggested that strategy for combatting obesity, and the pilot was so successful that it expanded to the whole school about five years ago.

In addition to adding movement throughout the day, the school added two extra physical education teachers. Just as academic teachers integrate movement into their classes, physical education teachers also work with students on academic skills. For example, an action-based learning class, teacher Kim Ward, will have students bounce on the trampoline while they practice reading words by sight, she said.

The school has cooking classes to help students learn to eat healthfully and the school doesn’t allow pizza parties or sweet snacks like birthday cupcakes. Instead, students are encouraged to bring in treats like fruit.

When students are more physically active, research suggests they are better at complex cognition — such as problem solving and remembering what they learn — and do better in school, said Amanda Szabo-Reed, a researcher at the University of Kansas Medical Center who recently summarized existing studies on activity and learning. There’s also evidence that students are better at focusing on tasks after moving, she said.

But research is not clear on whether there are benefits to combining movement and school work — something that Ostler and others at the school said is crucial to the school’s vision.

“There isn’t definitive research out there to say ‘it’s better to do your times tables while doing jumping jacks than to just do jumping jacks,’ ” Szabo-Reed said.

The practical benefits to combining movement and academics are real: Students at School 19 spend a lot more time being physically active than students at schools where the only opportunity for exercise is during a brief recess or gym class.

Comparing test scores over time doesn’t answer the question of whether the fitness program is boosting academic performance, Ostler said, because the student population has changed so much since School 19 became a magnet school.

But the school’s own measurements of students’ fitness have found gains every year, according to Ostler. And teachers say they see another benefit to moving more in class: Students are happier and more engaged during the day.

Megan Burt, an interventionist at School 19, was a first-grade teacher when the magnet program started. She said that students used to get bored in class, resting their heads on their hands. Now, they are more excited about coming to school and rarely seem disinterested.

“It’s hard to teach a group of kids who are just sitting there with their heads on their hands, bored, because then you start to get bored,” she said. “It’s exciting to see kids so excited about school.”