Purdue University won’t open the doors to its first high school for another five months, but its leaders are already planning for more.

Purdue Polytechnic High School will open this fall in Indianapolis with 150 freshmen taking part in a bold experiment: using a new project-based curriculum focused on science and math skills to better serve low-income students and students of color. As part of the Indianapolis Public Schools innovation network, the high school will also have an unusual structure, operating as part of the district but with the flexibility of a charter school.

“We really are targeting those kids who are in that middle range, who probably have the capability but aren’t necessarily planning on going to college,” said head of school Scott Bess. The goal, he said, is to build a diverse pipeline of graduates with the skills to thrive at schools like Purdue.

And before that first group of students has taken a single chemistry class, Bess and others say they’re confident in their vision — and think it could grow to as many as a dozen schools statewide.

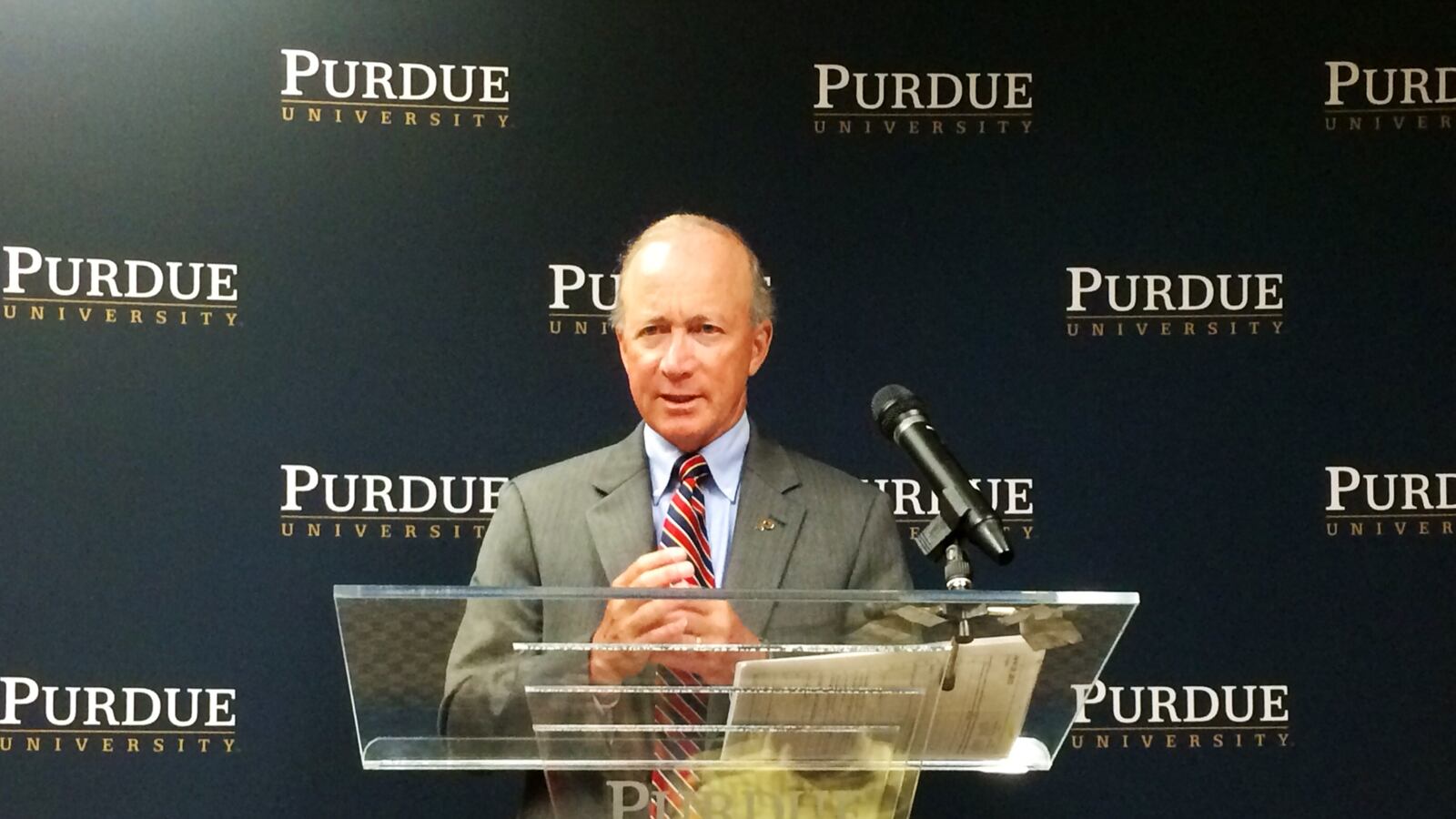

Purdue’s president and former Indiana governor Mitch Daniels “always had in mind that this would be more than a single high school,” Bess said.

“Assuming that the launch of this (school) goes well,” he said, “then we start looking at, what’s next?”

It’s a vision that’s winning them support. The school was recently granted $1.25 million by the Indianapolis-focused Richard M. Fairbanks Foundation to bring teachers on early this summer and lay the groundwork for expansion. The funding will help the school hire network staff with expertise in special education, financial management and technology.

Claire Fiddian-Green, president of Fairbanks, said that one reason they are supporting the school is that the city desperately needs more graduates with science expertise.

“We know we’ve got a big problem,” she said. The science, technology, engineering and math skills of local students “are really unacceptably low, especially for low-income and minority students.”

The school has some signs that it could pull the ambitious experiment off. Students from within the IPS district boundaries have priority for admission and will make up about two-thirds of Purdue Polytechnic’s freshman class. The rest of the seats were filled by lottery because the school received hundreds more applicants than available seats — one sign that there is enough demand to support another Indianapolis campus, Bess said. He attributes much of the strong early interest to the Purdue brand. (Graduates who meet Purdue’s admission criteria will automatically win spots at the university.)

But this first school still has its own challenges to face. It will use a new, untested curriculum and target relatively high-needs students who may not come in with strong science backgrounds. It also is entering a crowded market of high schools, as Herron High School opens a new campus and IPS plans to reconfigure its half-empty high schools.

Bess said any expansion is contingent upon the success of the first school. But Purdue faculty will be studying the school, and if the model does work well, the lessons could spread beyond the Purdue high schools, said Fiddian-Green.

“We hope that we learn lessons about how to teach STEM subjects more effectively to teachers regardless of the school environment,” she said. “Other schools around the state, traditional schools could adopt their models.”