When Indiana gave out school ratings last fall, Central Christian Academy’s board called an emergency meeting.

The school had gotten another D, and once again it would not be able to receive new vouchers, the public money that Indiana gives many families to help pay private school tuition.

With Central Christian cut off from hundreds of thousands of dollars in state aid, board members contemplated closing the school.

Losing voucher dollars was “catastrophic,” said David Sexauer, who served on the board before taking over as head of school this year. “If it wasn’t for the fact that the church was willing to step in and help us kind of keep going, we would’ve had to close our doors.”

Ultimately, Central Christian Academy had its grade revised upward to an A because of changes to the way Indiana evaluates schools and its own improved passing rate on state tests. Now, instead of closing down, the school is hoping another round of solid scores this year will allow it to begin accepting vouchers again.

“It was like a roller coaster,” said Principal Melanie Sims.

Central Christian’s experience reflects a defining feature of Indiana’s school voucher program: Private schools can live or die by test scores the way that public schools often do, in an arrangement that divides school-choice advocates.

In the five years since Indiana began offering vouchers, the program has grown into one of the largest in the nation, and about $146 million in public funding was funneled to Indiana private schools through vouchers this year. But that money comes with strings attached, and low test scores have cost 16 schools the right to accept new vouchers. At least three have closed.

“I can’t think of any way you could make the program more accountable,” said Michael Petrilli, president of the pro-voucher Thomas B. Fordham Institute. Indiana’s accountability requirements, he said, are at the “far end of the spectrum.”

Most states with voucher programs impose regulations on private schools that accept the public funds, but those guidelines vary widely. Some programs have health and safety requirements, in Florida new schools must show proof of financial stability, and in Louisiana schools are not allowed to use selective admission for students receiving vouchers.

But the question that generates the most controversy is whether and how voucher-funded schools should be held accountable for helping students learn.

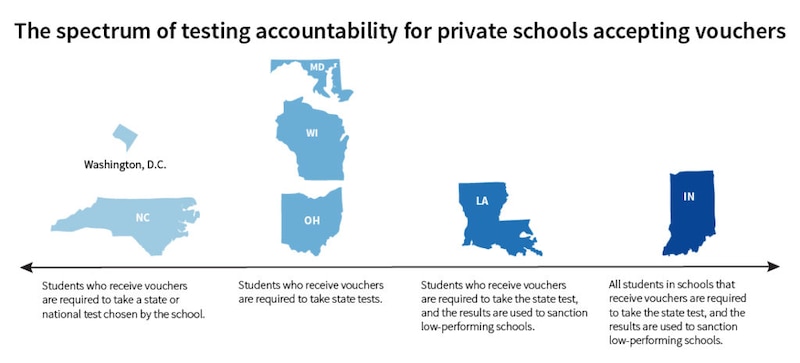

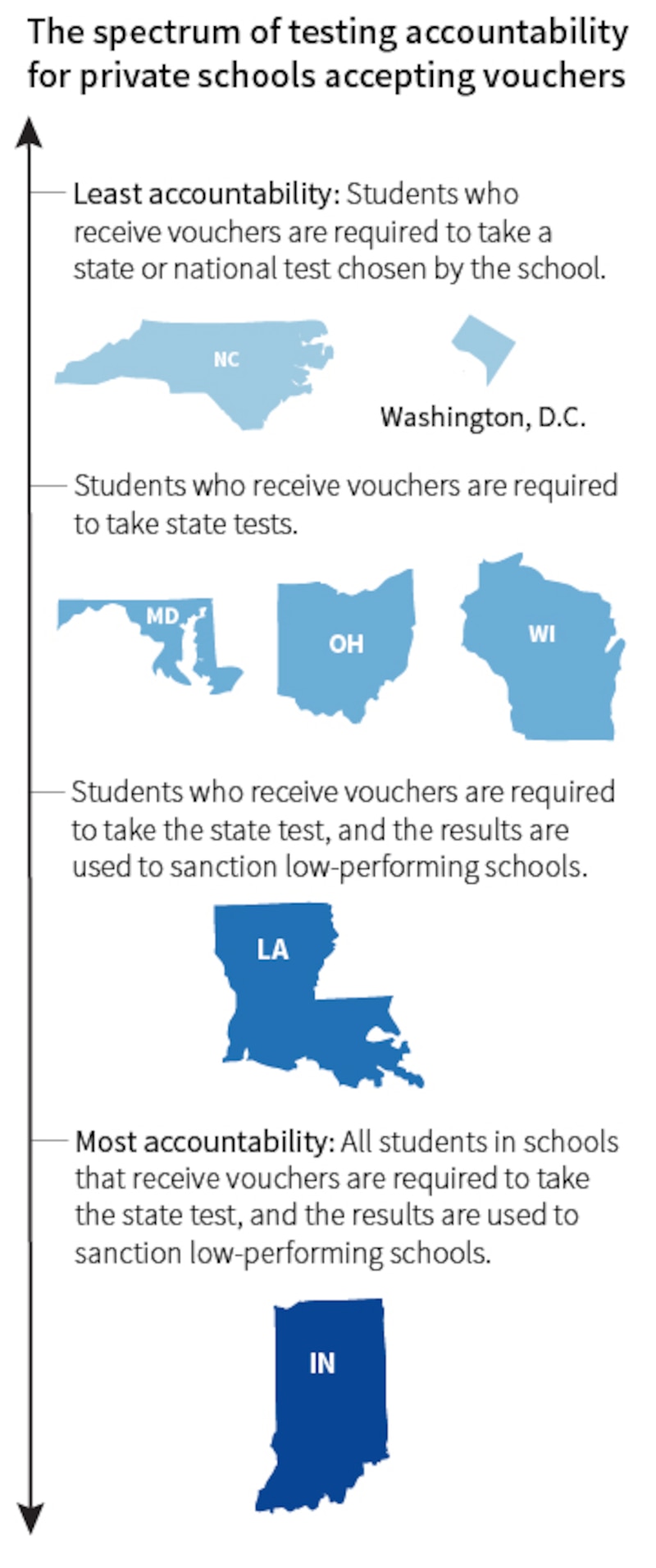

Many voucher advocates — including American Federation for Children, the pro-voucher advocacy group U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos headed before joining the Trump administration — say they’re open to seeing students who use vouchers take tests, but don’t push for individual schools’ scores to be provided to anyone but parents and academic researchers. That’s the course that North Carolina has so far taken and that the federal government charted for the Washington, D.C. voucher program.

Other states have chosen to have voucher students take state exams to allow for comparisons between private and public schools. Some of them even penalize schools whose voucher students’ scores are low.

Indiana goes a step further: It not only requires students who are receiving vouchers to take state tests, it also requires private schools to test students who are not receiving state aid. Those test results, and other measures like graduation rates, are used to assess private schools with the same yardstick as charter and traditional public schools — A-F grades from the Indiana Department of Education. When schools have chronically low grades, the state sanctions them by reducing their access to vouchers.

So why did Indiana — which has embraced so many elements of the school choice agenda, including charter schools, open enrollment across district lines and vouchers — come to accept this requirement?

One explanation is that the state’s voucher program was born at a time of peak accountability fervor in Indiana. Former-Gov. Mitch Daniels and State Superintendent Tony Bennett were pushing for dramatic changes in education policy, including a new focus on punishing public schools with chronically low test scores.

The other answer: sports and the other benefits for private schools that were already contingent upon state testing in Indiana.

Many private schools were already taking state tests and getting letter grades before lawmakers rolled out the voucher program in order to get state accreditation — a badge of approval. Some Indiana schools were eager for state accreditation because it was a prerequisite for them to participate in the state’s high school sports association, said John Elcesser, executive director of the Indiana Non-Public Education Association, which represents private schools across the state.

But mainly, state accreditation was a way for private schools — including many Catholic and Lutheran schools — to show parents they were on par with public alternatives and get access to state grants, Elcesser said.

“For those schools, it was a very easy lift coming into the voucher program,” he said, “because most of the requirements they were already meeting.”

The unusual reality in Indiana before vouchers, with many private school students already taking state tests, allowed lawmakers to easily decide the crucial question of what to do about testing in private schools. But nationally, it’s a question that has ignited vigorous debate among voucher advocates and private school leaders.

Private schools often choose to administer a national standardized test in order to give parents more information on how their children are doing. Joe McTighe of the Council for American Private Education, a national umbrella group, said he’s comfortable with having that be required in exchange for getting public funds, but not with requiring private schools to administer state tests.

“We prefer a really light touch when it comes to accountability,” McTighe said.

Voucher advocates often argue that private schools don’t need to be measured with state tests because there is another form of accountability: parent choice.

That’s what Jay Greene argues. Greene, who heads the Department of Education Reform at the University of Arkansas, has written that test scores don’t capture long-term benefits from schools like graduation rates and earning potential. And they don’t measure important issues like school culture.

Parents have “a lot more information on average than do well-meaning but distant bureaucrats,” Greene said. “I’m not saying that this is scientific, but the science is even cruder than the kind of information that parents have.”

But many school choice advocates say parent judgments alone aren’t enough to ensure quality. That includes Sexauer of Central Christian, who says he still supports accountability measures for voucher-funded schools even after watching his school come near to closing.

“Parents don’t know everything,” Sexauer said. “Parents are not professional educators. Parents don’t ask the same kinds of questions that the department of education is going to ask.”

When taxpayer dollars are on the line, the state should do its best to ensure those schools are teaching students, said Fordham’s Petrilli.

“If we have data — especially some kind of growth data — and it shows that kids are not learning anything in that school year after year, I think that is clearly a waste of taxpayer funds,” Petrilli said. “There’s an appropriate government role in … saying, ‘Hey, there’s going to be a handful of schools that are so low-performing that we’re not going to allow them to be a part of the program.'”

Making sure vouchers don’t allow students to end up where they learn less: that’s the reason for Indiana’s strict accountability rules. But Central Christian’s experience illustrates the challenge that can pose for schools, too.

Vouchers themselves were a boon for the school, which had been shrinking as congregants from the affiliated church migrated to the suburbs. The state funding attracted low-income families from the neighborhood, and enrollment at the tiny school swelled. At its peak, more than 60 percent of students received state aid.

Many of those students were less prepared than past students had been — and less likely to post high test scores, Sexauer said. “We weren’t used to that.”

Meanwhile, Indiana has spent years grappling with changing standards, tests and accountability systems. That means the academic success of private schools, like public schools, is being judged by a set of particularly controversial and imperfect measures.

Indiana’s policies actually give private schools an even shorter and stricter timeline to improve than public schools face. If a private school gets a D or F grade from the state for two consecutive years, it is no longer eligible to receive vouchers for new students.

That’s what brought Central Christian to the brink of closing. But the school is on track to get new vouchers again. Its score jumped when the state changed how it measures schools to give them more credit for “student growth.” Now, even if children are not passing the state test, schools can earn high marks if their students see their scores rise over time. Central Christian officials say the change helped a lot.

Even before the grading shift, the school made changes that advocates of strong accountability could tout as a success — and a few that advocates for an unfettered school-choice marketplace see as worrying.

The prospect of losing state funding meant that Central Christian leaders went all in on a plan to improve teaching and test scores and to do a better job with students who came in behind. They brought in an outside consultant who helped revamp their instruction, building in more regular teacher training and adding more tests to see what students were learning throughout the year.

And they started following the state’s blueprint for what students should learn, and when. Before Central Christian started taking vouchers, Sims said she was a bit “oblivious” to state standards or tests. But now school leaders use Indiana’s standards to make sure that students on are track to know material by testing time.

For some choice advocates, that illustrates what’s wrong with Indiana’s strict accountability system. One reason why McTighe criticizes mandated state testing for private schools is because it pressures private schools to follow state standards, teaching the same material in the same order as public schools.

“If every school is the same, there is no choice,” McTighe said. “We have replaced genuine school choice with kind of an appearance of school choice.”