Two Indiana senators — a Republican and a Democrat — are calling for the state to reform how charter schools are overseen.

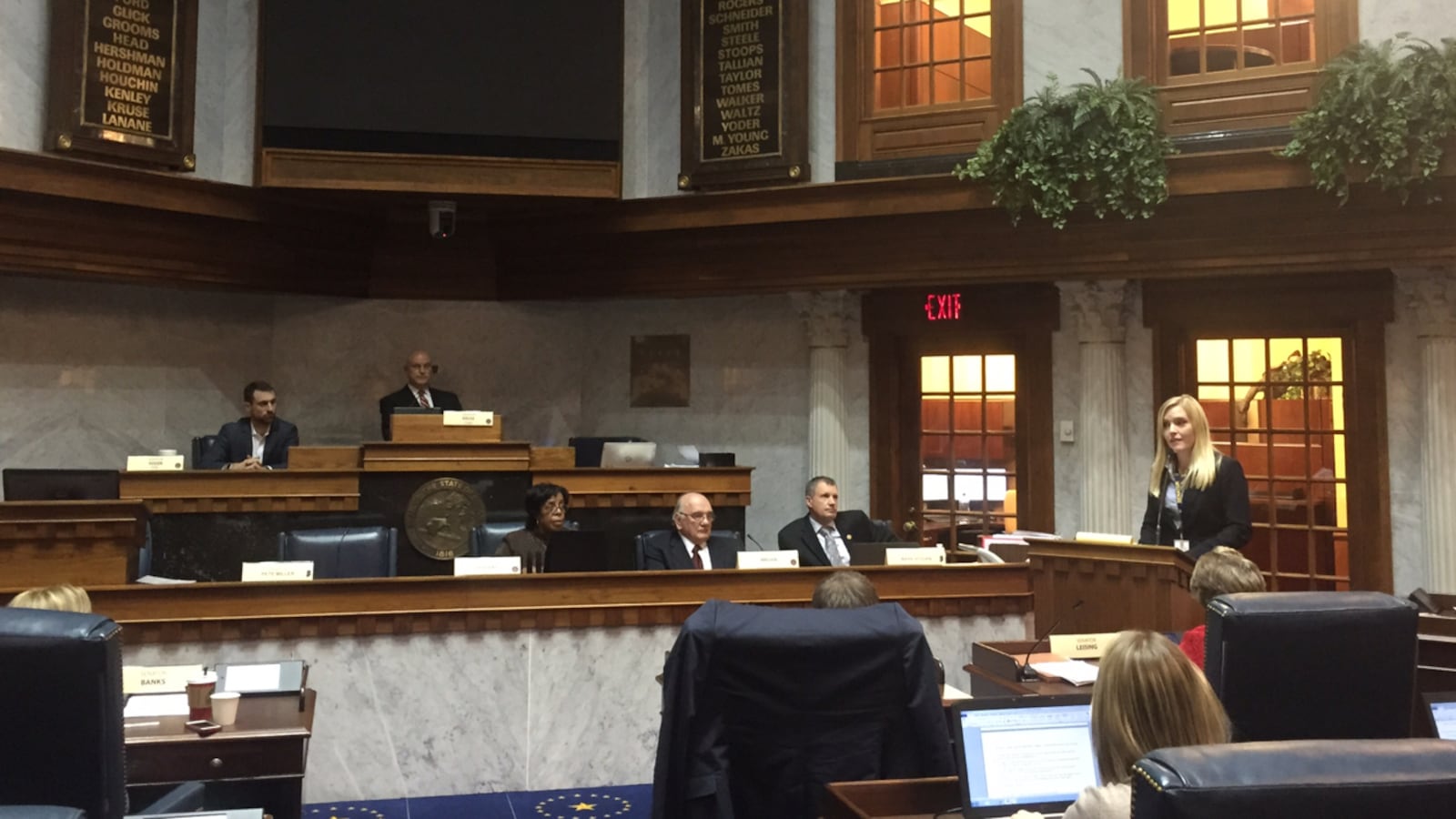

Sen. Dennis Kruse, an Auburn Republican who chairs the Senate Education Committee, and Sen. Mark Stoops, a Bloomington Democrat also on the committee, have each proposed a bill to ensure charter school authorizers cannot open new schools or renew charters without evidence that students are learning.

The bills come two months after a Chalkbeat investigation revealed that while the small Daleville Community School District charged with overseeing Indiana Virtual School has appeared to follow state law, it isn’t necessarily meeting the needs of the school’s thousands of students.

Special Report: As students signed up, online school hired barely any teachers — but founder’s company charged it millions

The district was on track to earn at least $750,000 in fees last year overseeing Indiana Virtual, which over its six-year lifespan has earned two F-grades and, in 2016, managed to muster only single-digit graduation rates. The school continues to bring in millions of state dollars for its students, and in September, opened up a second school, also chartered by Daleville.

Kruse’s Senate Bill 350 says an authorizer cannot offer a contract, or charter, to an existing organizer unless its current students are achieving academically. Organizers are nonprofits that run charter schools. They’d have to provide evidence that could include test scores, attendance rates, graduation rates, increased numbers of students taking advanced classes or earning honors diplomas.

The bill would require the Indiana Department of Education to create rules by Nov. 1 to prevent charter school organizers from committing financial or enrollment “fraud, waste and abuse.” Schools would also have to submit an annual report that includes audits, the most recent enrollment count, and a list of employee salaries.

Currently, Indiana authorizers — which include universities, mayors, or school districts — can only be punished for their school’s bad academic performance, not other kinds of missteps. This bill would empower the state board to more closely scrutinize and take action regarding charter schools and authorizers.

If the department finds the school was in violation, the department would be required to tell the organizer and recommend that the state board do one of the following:

- Require the school’s authorizer to revoke its charter,

- Withhold funding from the school, or

- Require the school to take action to remedy its problems.

Stoops’ Senate Bill 315 goes even further by placing more restrictions on authorizers that are school districts or universities. He said he wasn’t aware that Kruse was offering a bill on the same topic, but that he looks forward to talking with him about it. He’s worked unsuccessfully before to regulate authorizing, but new information about online charter schools has spurred him to address it again this year.

“Charter schools are a little out of control,” Stoops said. “They continue to take students even when they fail, and the whole issue of how authorizers get a cut of their funding, so there’s a lot of incentive for authorizers to create these new schools.”

The bill removes the 2015 grandfathering provision that let existing authorizers avoid screening by the Indiana State Board of Education before they were allowed to open charter schools. Under the bill, these authorizers must now be screened before they can renew existing charters or authorize new schools.

The bill does not change the fact that the state board does not screen school districts, such as Daleville, but instead requires them to register as authorizers, and they are automatically approved.

Stoops also included language in the bill that would give charter school authorizers stricter rules around what state grades are needed to open or renew schools. The bill says that an authorizer may not sponsor a charter school if that school’s organizer already runs a school in Indiana that has received a D or F grade for two consecutive years.

Like in the state’s voucher law, grades would be factored into whether charter schools can enroll new students under Stoops’ plan.

Starting July 1, a charter school that earns a D or F for two consecutive years cannot accept new students for one year. If the school earns a third D or F, the school may not accept new students until it earns a C-grade or better for two consecutive years. If a school earns an F grade for three consecutive years, it cannot enroll new students until it has received a C-grade or better for three consecutive years.

The bill also would eliminate the fees all authorizers can collect for overseeing schools starting in July. Now, authorizers can get up to 3 percent of a charter school’s state funding.

Although these provisions don’t apply to all authorizers, David Harris, executive director for The Mind Trust, said he worries aspects of both bills infringe on the autonomy that can also make charter schools successful. The Mind Trust works closely with Mayor Joe Hogsett’s office on supporting mayor-sponsored charter schools in Indianapolis.

“Specific rules written to restrict the decisions of authorizers will not transform bad authorizers into high-quality authorizers,” Harris said.

This early in the session, it’s hard to say how far such proposals will get. Committee chairs like Kruse tend to advance bills they author, but Stoops’ bill faces another hurdle: Democrats are in the vast minority in the General Assembly, and it’s the majority party that has the discretion to say what merits discussion. That said, Gov. Eric Holcomb, a Republican, has already committed to working with the state board to look into virtual schools.

Ultimately, Stoops said that the track records and poor performance of some charter schools and online schools speak for themselves, and he thinks it’s causing policymakers to take a second look at how to regulate them.

“How do they get away with it?” Stoops said. “I think that’s definitely worth dealing with.”