The tension was rising in Amanda Moore’s class. Fourth graders were facing off against a dragon-like Sea Raptal, and it was a close fight. Victory hung in the balance.

“What is the universal theme of our text?” asked Moore, calling on a boy to explain a story students had been reading in small groups. His answer — to treat others as you want to be treated — was correct, leading to the defeat of the monster, and causing the class to erupt in chatter and cheers.

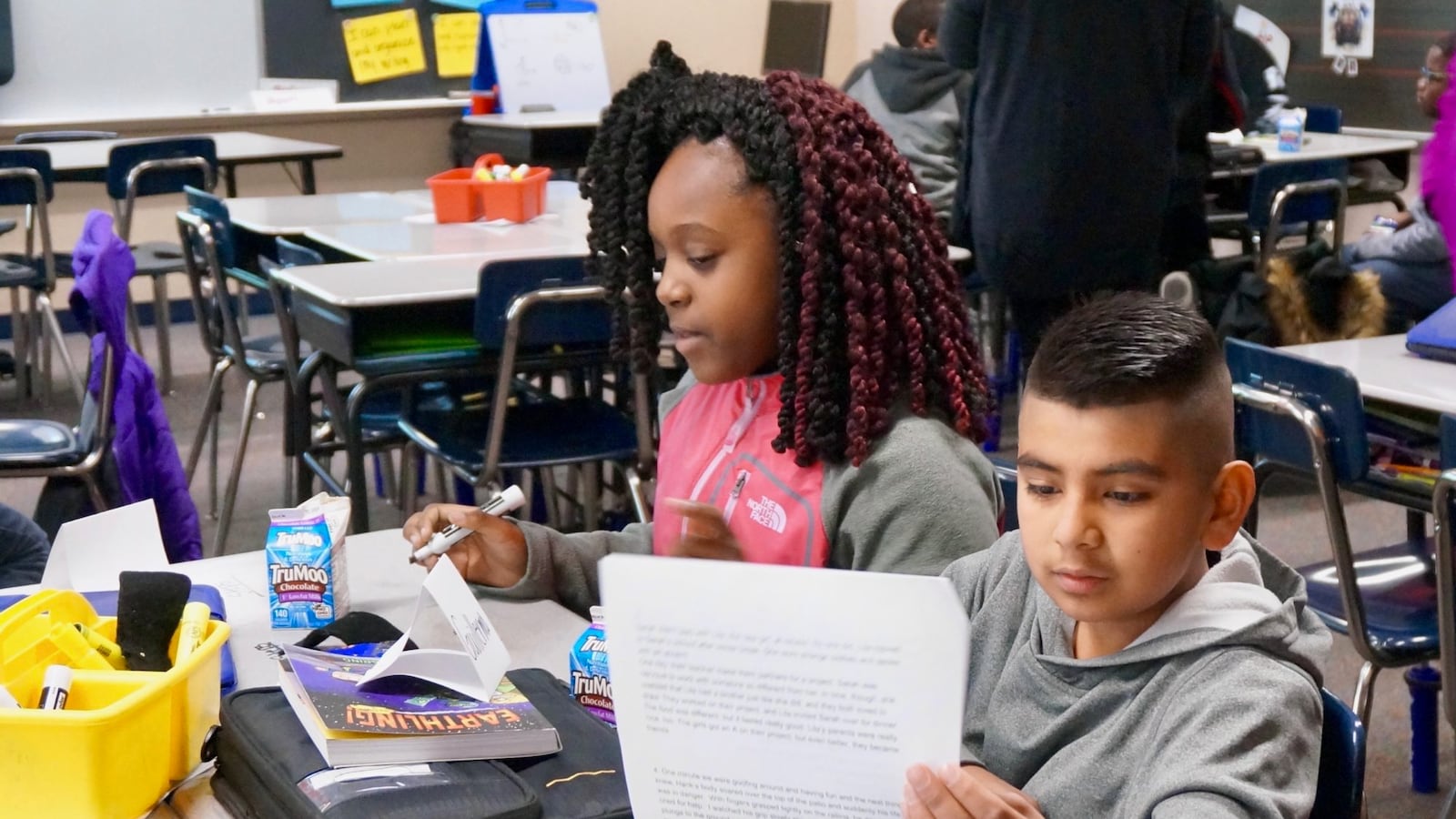

All this excitement is because of “gamification,” a new approach Moore recently began using in her fourth-grade class at Chapelwood Elementary School in Wayne Township. With the help of an online platform called Classcraft, which allows students to inhabit characters, earn points, and complete quests, Moore designs adventures that entice students to practice math and reading skills.

Gamification is a growing trend in education that aims to use games to engage students in school work. Critics, though, raise concerns about students spending too much time on screens and the quality of the games. But games are becoming increasingly popular among teachers, and research suggests that games can improve student scores in subjects such as math and history.

Moore, who has taught at Chapelwood for a decade, learned about gamification recently while completing a master’s degree in curriculum and education technology at Ball State University. Since she started using games to teach in January, it has totally transformed the class, Moore said. Now, she is building positive relationships with students because she is playing games with them.

“We forget that kids are kids, and they want to play. And they are motivated by play, and they learn through play,” she said. “Gamification allows us to get back to that a little bit.”

This week is spring break, so Moore is working with a group of students who are slightly below grade level in reading for intersession. When the week began, Moore told the students that they were on a magical boat that was shipwrecked. As a class, they must collect enough crystals for their ship to set sail again.

In part, the game is based online, and students can bring laptops from school and keep playing at home. There is an adventure map, and every student has a character. Students can earn points online by completing assignments where they practice making inferences and identifying themes, and Moore can see how they are progressing. But the game is also the backdrop for other work, and the class sometimes comes to a halt when students face random events, where they can win or lose points.

“It’s fun because you can learn while you are playing a game,” said Lilly Mata-Turcios, a student in the class.

Since Moore started using online gaming, students have been more engaged, and they’ve continued to do school work at home so they can win rewards such as new armor for their characters or pets, she said. The class has built a strong community because students have to work together to defeat monsters like the Sea Raptal, Moore said.

“It’s a model of what personalization can look like in a blended classroom,” said Michele Eaton, the district director of virtual and blended learning.

During most weeks, students spend about an hour each day completing math and reading assignments through Classcraft. Moore also works with small groups and does instruction with the whole class. But everything they do takes place against the backdrop of their adventure.

“I think it’s just a really powerful way to teach,” Moore said. “It is absolutely worth the time.”