Indiana preschoolers with disabilities have received the same $2,750 from the state for more than 25 years, even as advocates say the cost to educate them has risen dramatically.

The amount hasn’t changed despite inflation, cost of living increases or statewide attention on preschool, leaving local districts to shoulder the rest of the cost. That means taking money out of already cash-strapped budgets at the expense of things like teacher raises, smaller class sizes and additional programs.

Across the state, 13,066 students qualify for special education preschool services, up from 4,004 in 1991, the earliest available data from the state. At $2,750 per child, that amounts to almost $36 million this year that Indiana is sending to districts.

Read: Why Indiana ranks second to last in the nation for access to its pre-K program

Advocates say that’s not enough and are making a push ahead of next year’s legislative session to demand more funding from the state for the programs.

“We don’t have any districts where the funding matches the expenditures,” said Tammy Hurm, who handles legislative affairs for the Indiana Council of Administrators of Special Education. “It’s something we’ve always advocated for, but we just decided in the last year that it needs to be our primary focus.”

As politicians consider ways that Indiana could increase funding in the wake of declining state revenue, they are turning to the federal government to increase its contribution to the special education preschool program, a no-cost option for families once their children turn 3.

“The federal government has always underfunded their commitment,” said Rep. Tim Brown, chairman of the influential budget-writing House Ways and Means Committee. “That’s why the number has kind of been flat from the state.”

Under the federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, states are required to offer early education services to students age 3 to 5 who have disabilities. As far back as 1975, federal officials said the goal was to fund 40 percent of the extra costs associated with educating those students. But that promise was never fully kept.

The current funding level for IDEA is 15 percent, and the highest level in recent years was 33 percent after extra funding came in from the recession in 2009. The recently passed federal spending bill did increase funding for developmental preschool grants by $13 million, but split between states, it’s a small boost.

Brown said special education advocates came to him with a request for more special education preschool dollars for 2019, when lawmakers will meet to craft a new two-year budget. Brown said that was the first time he was confronted with the fact that funding had remained flat for so long. It’s on his list of issues to consider next year.

“We made a commitment to these children and this project,” Brown said. “It’s time to look at what the state can do.”

There’s no specific ask in mind because costs can vary widely. But estimates put together by the Indiana Council of Administrators of Special Education put costs anywhere from $2,800 for students needing just speech and language services to nearly $12,000 if the student needs speech, physical and occupational therapies. The majority of students won’t need such intensive therapies, but the cost of even mild interventions outpace what the state allocates to support them.

The state’s On My Way Pre-K program offers preschool tuition to families of 4-year-olds, but lawmakers have only approved about $74 million for the program since it began in 2015. Students with special needs can qualify for the state preschool program, as long as their families meet the eligibility requirements.

In Indianapolis Public Schools, where 519 students receive special education services in preschool, the state contributes $1.265 million, and $261,178 comes from federal funds for a total of about $1.5 million. But annually, those students require services that cost upwards of $4.7 million. The extra $3.2 million comes out of the district’s operating fund.

“Some kids may just need speech therapy or occupational therapy, and they’re best served in a typical pre-K setting,” said Brent Freeman, IPS’ director of special education. “But the funding is the same for every pre-K student.”

Freeman said the lack of funding is especially frustrating because the district can see that developmental preschool is helping children learn. While most still leave for kindergarten below the state average for “age appropriate functioning,” according to Indiana’s kindergarten readiness test, 91 percent of the students made big improvements.

“It does justify the investment,” Freeman said. “We know we can grow students, we can help them grow, and yet with the (funding we have), we are still falling short of even state average for kindergarten readiness.”

It’s a domino effect, he said. The more students with special needs fall behind, the less likely it is that they’ll be able to eventually join their peers in typical classrooms. But it’s exactly that participation with general education students that can push them to learn and catch up more quickly in time for third-grade reading and other milestones, Freeman said.

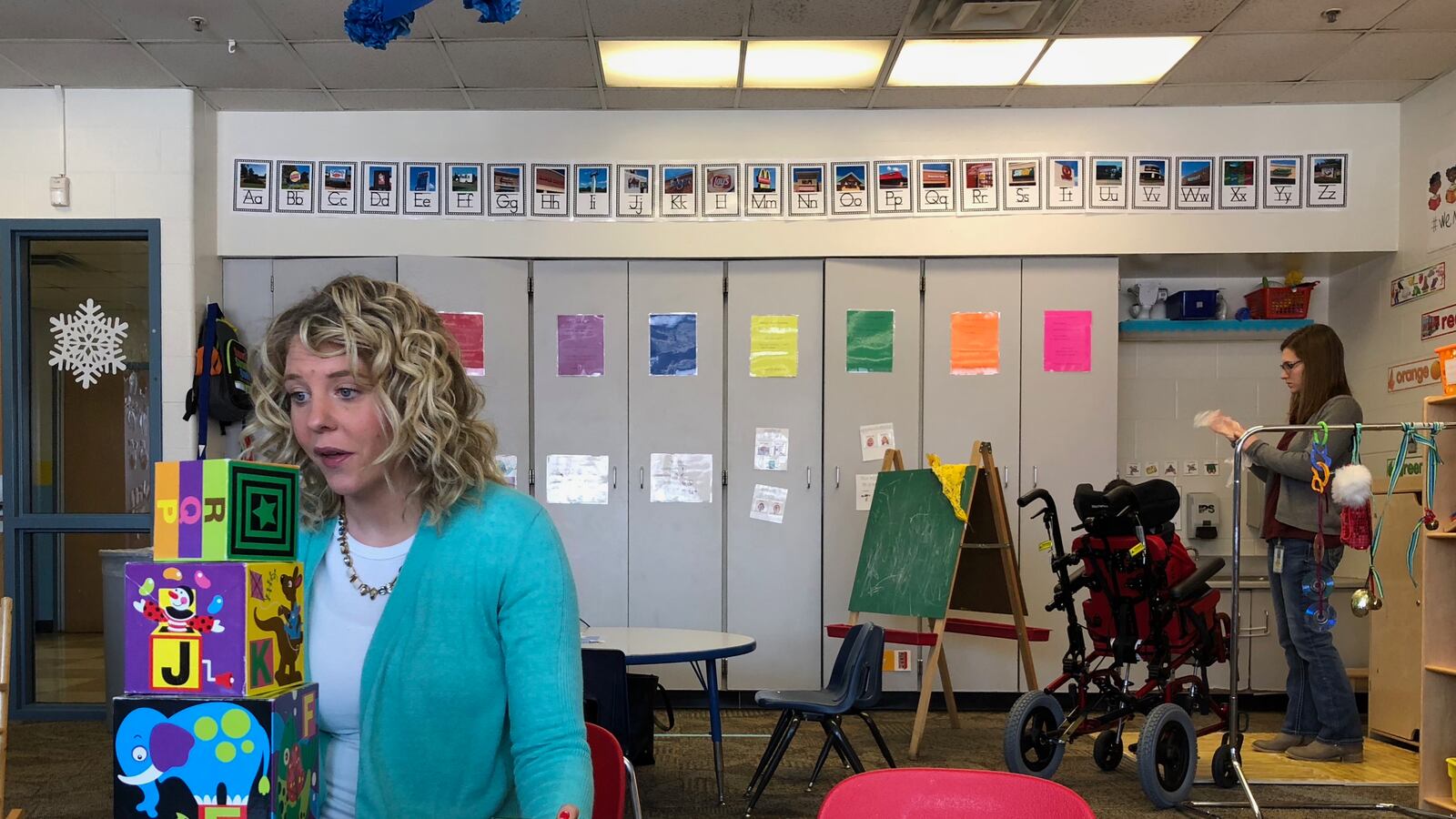

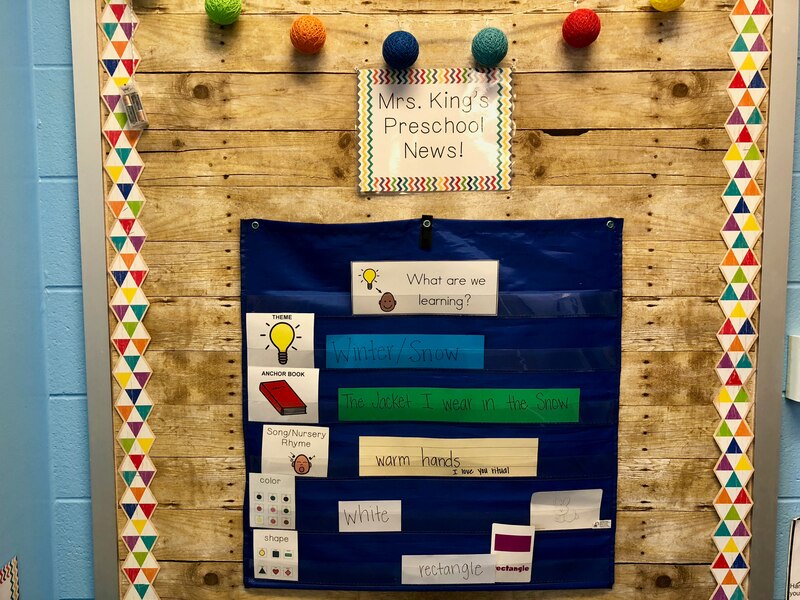

At IPS School 48, Cate King has two half-day classrooms devoted to preschoolers with disabilities. Her students’ needs run the gamut, she said — some just need some extra language support, while others require physical therapy and feeding. It’s her third year at the school, which pulls students from across the city.

On an afternoon this winter, her students spent time reading, doing puzzles, refining scissor skills and playing with trains and boxes. Those activities, especially the playing, aren’t uncommon in any preschool classroom, King said, but for her students there’s more emphasis on using visuals and developing language.

One young boy had grown attached to a brightly colored tablet device. King said tablets and other assistive devices, as they’re called, help students communicate and practice speaking.

Over and over again, the boy practiced his letter sounds and matched letters to pictures.

“Who’s that?” King asked, pointing to Elmo on the screen. “Say Elmo!”

“Elmo!” he repeated.

“Good job,” King said. “Where’s A? Ah Ah Ah.” She makes the sound as he searches for the letter and points to it.

All this work is done in anticipation of his reward: A dance break to a jazzy alphabet song enthusiastically led by Elmo.

Other students build train tracks in the shape of figure-eights and circles, needing a few gentle reminders from King to share the train cars. Much of the day is like this, she said, with a couple 10- to 15-minute whole-group lessons, but mostly, lots of play and smaller activities designed to get the students to improve verbal skills, and learn how to interact with their peers.

King’s students might also get pulled out for other physical or occupational therapy, medical services or support for students who are blind or low-vision.

“It’s not really developmentally appropriate to sit and work much more than we do,” King said. “The bulk of what we do is play, but we are learning.”

King said she has purchased many of the toys and materials in her classroom, and some things were leftover from previous teachers.

“Since I’ve been here, we haven’t had a stipend that we’ve gotten,” King said. “Our school provides paper, crayons, stuff like that, but as far as big stuff, toys … that’s just stuff that I’ve gone to purchase.”

And King’s personal spending isn’t unusual, advocates say. When districts have to dip into operating funds, mostly used to pay for teacher salaries and benefits, there’s just less to go around.

“The trade-off is you can’t give raises,” said Weston Young, chief financial manager for the district. “Eventually that is a self-perpetuating problem because then you can’t attract people and retain them.”