When Jeremy Baugh took the helm as principal of School 107 three years ago, staff turnover was so high that about half the teachers were also new to the struggling elementary campus, he said. For his first two years, the trend continued — with several teachers leaving each summer.

“In the back of my mind,” he said, “I just kind of had assumed that that was going to be the norm — that I was going to have to always be on the lookout for good talent.”

But when he surveyed his staff this year, Baugh got some unexpected news: about 97 percent of teachers said they plan on returning. “I was thrilled,” he said.

Staff say the change is heavily driven by a new teacher leadership program Indianapolis Public Schools has rolled out at 15 schools. Known as opportunity culture, some teachers are paid as much as $18,300 extra per year to oversee and support several classrooms. Educators at School 107, which is also known as Lew Wallace, say opportunity culture helps retain staff in two ways: It gives new teachers, who can often feel overwhelmed, support. And, it allows experienced teachers to take on more responsibility without leaving the classroom.

As districts across the country struggle to hire teachers — particularly in hard-to-fill specialties such as math and science — many schools are especially interested in retaining the teachers they have. Although there is little research directly linking leadership opportunities with retention, there is some research suggesting one reason teachers leave the profession is because they feel they don’t have influence in their schools and they have few opportunities to advance.

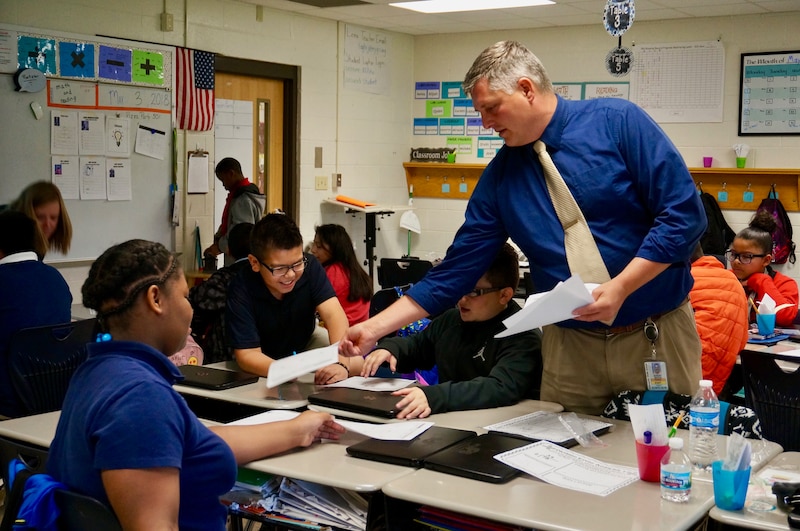

At School 107, which began the program last school year, there are three multi-classroom leaders who each oversee several classroom teachers. Their role is to offer advice, training, and support to their peers. They are ultimately responsible for the test data in all the classrooms they oversee.

One of those teachers is Deanna Schmidt. With five years of experience and a masters degree, she was looking for a job where she could train teachers and continue to work with students.

“I loved teaching but I just wanted to do something different. I had kind of tossed around the idea of maybe going back for an admin license,” she said. But “I don’t really want to be a principal.”

Instead, Schmidt left her job at the Butler Lab School to work as a multi-classroom leader at Lew Wallace. “I think I found the perfect fit,” she said.

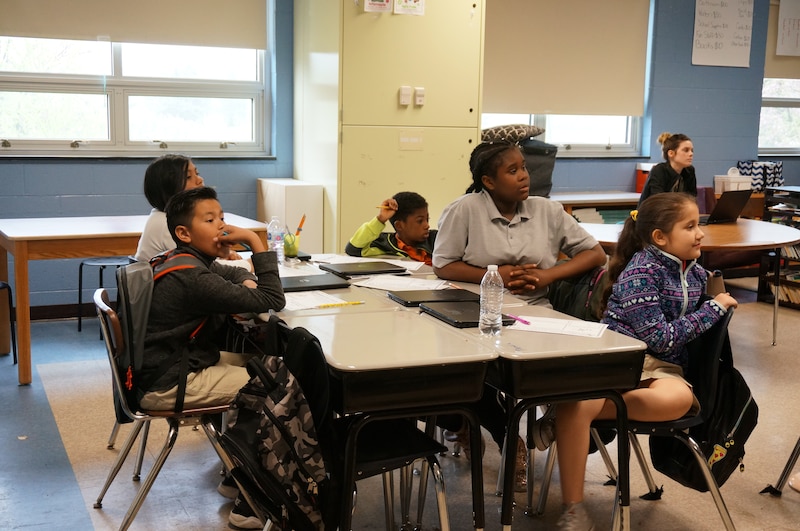

Lew Wallace is one of the most diverse campuses in the city. The neighborhood it draws from, near Lafayette Square, is full of recent immigrants and refugees. And that’s reflected at the school, where 38 percent of students are learning English.

That’s just one of the challenges facing students and teachers. Over 80 percent of students come from families that are poor enough to qualify for free lunch, according to state data. And mobility at the school is so high that more than half of its 606 students are new this year, Baugh said.

The result is that teaching at School 107 can be particularly hard, Baugh said. In one classroom, for example, there might be several students who are learning English — who the teacher struggles to communicate with — and four children with difficult behavior, he said.

“Those four children create kind of this shaken pop bottle syndrome in the classroom where everybody feels on edge,” he said. “That can be difficult to teach in because you don’t have this sense of calm all the time.”

School 107 has long struggled on state tests. Fewer than a quarter of students passed the state ISTEP exam in 2016-2017. Over the last two years, however, individual students have made gains in test scores from one year to the next. Those improvements began before the school started using opportunity culture. But a recent study of three districts using the teacher leadership model found multi-classroom leaders raised student math scores — although they did not appear to raise reading scores.

The idea behind opportunity culture is that teachers — especially newer teachers — are not alone in handling challenges. They have mentors helping them in a range of ways — including modeling lessons, pulling small groups, and working on lesson plans.

Abby Campbell, who is in her first year teaching, has 31 students in her fourth grade class. Her students run the gamut from those who are far below grade level to those who are above it. Close to half of them are English language learners, and about five have special education plans, she said.

When she started teaching, she was overwhelmed. “I had a lot of nights with tears, and not sure if I was going to survive the year,” she said.

Campbell not only survived the year but plans on returning in the fall. One of the main reasons, she said, is because of the support she’s gotten from her multi-classroom leader, Jessica Smith. Smith helps Campbell with nearly all the pieces of her job — from lesson plans to emotional support, said Campbell.

“I can’t even imagine doing it without Jessica,” she said. “I would’ve been a hot mess.”

Initially, some teachers at Lew Wallace were uncomfortable with having multi-classroom leaders essentially overseeing their classes. But the classroom leaders are supposed to be team members, and most teachers are more at ease now that they’ve gotten to know them, staff said.

“I was wary,” said Steve Carr, who teaches sixth-grade math. But Brandon Warren, the classroom leader he works with, helps him without being prescriptive, Carr said.

“It’s not me telling you what to do. It’s what we’re going to do together,” Warren said.

Multi-classroom leaders also lead regular training for teachers. After struggling to tackle everything during teacher training, the multi-classroom leaders at School 107 eventually decided to focus on a small number of issues. This year, they are working on strategies for improving student writing and for keeping students engaged — particularly English language learners, who may not feel comfortable answering questions in front of the class.

Because so many of their teachers are returning next year, they will be able to move on to new focus areas — strategies for teaching math and English language learners — instead of repeating the same teacher training, said Smith, one of the classroom leaders.

“It’s so hard to keep training new teachers all the time,” she said. “If we can keep our teachers, they are going to be such a higher caliber because we’ve put our time into them, and we’ve invested in them.”