Earlier this year, La Wanda Girton’s son was facing a three-day suspension from Tindley Accelerated School for handing a pencil to another student.

A teacher was trying to settle down the class, she said, and told the students to be quiet. But when Edwin, a sophomore, lent a pencil to a classmate in need, he said, “Here you go.”

Tindley’s network of six charter schools has long been known for strict discipline policies imposed alongside rigorous college prep. But after 14 years and some of the highest out-of-school suspension numbers in the state, the Indianapolis charter network is relaxing its controversial, unapologetically tough approach to discipline in the upcoming school year, Tindley CEO Kelli Marshall told Chalkbeat, in an effort to reduce suspensions and better serve students and families.

“Things are changing,” Marshall said. “Maybe we have to loosen some bolts a little.”

In the next school year, Tindley will move away from automatic suspensions for minor infractions, such as chewing gum and repeatedly coming to class unprepared, Marshall said. Instead, the network will adopt a demerit system, where students accumulate points for misbehaving and face suspensions after reaching a certain number of points.

The flagship high school will also loosen several signature rules — allowing vending machines, longer hairstyles on male students, cell phone use before school and during lunch breaks, and longer passing periods between classes. Gone will be the silent transitions while students stand in line waiting to be dismissed.

“It was a very, for lack of a better word, militaristic way of running the building,” Marshall acknowledged.

The decision to relax the rules came in part from feedback from students and families concerned that some rules were unreasonable. The changes, Girton said, are “well overdue.”

The relaxed rules could offer myriad benefits for Tindley, a cash-strapped network trying to stabilize after fast growth and troubled leadership while facing increasing competition from other charter schools — all during an educational moment that is embracing a gentler approach to discipline.

The changes could keep students — the Tindley term is “scholars” — learning in classrooms instead of sitting out a suspension at home. They could make Tindley more accessible to students who act out because of their backgrounds in poverty or traumatic situations. And they could stem dropouts and retain more students, including those who might be leaving Tindley schools because of excessive discipline.

While charter schools with “zero tolerance” or “no excuses” discipline philosophies often see high academic results, those approaches have also faced heated criticism nationally for being so rigid that, for example, students aren’t even allowed to use the bathroom.

Still, at least one local education expert says even Tindley’s revamped policies could do more to address misbehavior in a preventative way, rather than a reactive one.

“You want to avoid children being suspended, period,” said education consultant Carole Craig, a former education chair for the Indianapolis NAACP who has been critical of Tindley’s strict discipline.

“Chewing gum, not having books, talking out in the hallway — those are misbehaviors, certainly, but why would you want to get to the most extreme on even adding up points and leading to a suspension?” she added.

Craig advocates for a positive discipline system that addresses the root causes of behavioral issues, as well as training for teachers in urban schools on implicit biases and working with children who may be acting out because of traumatic experiences at home.

Nationally, this is part of a larger conversation about stemming disparately harsh discipline against black boys in particular, in addition to Hispanic students and students with special needs.

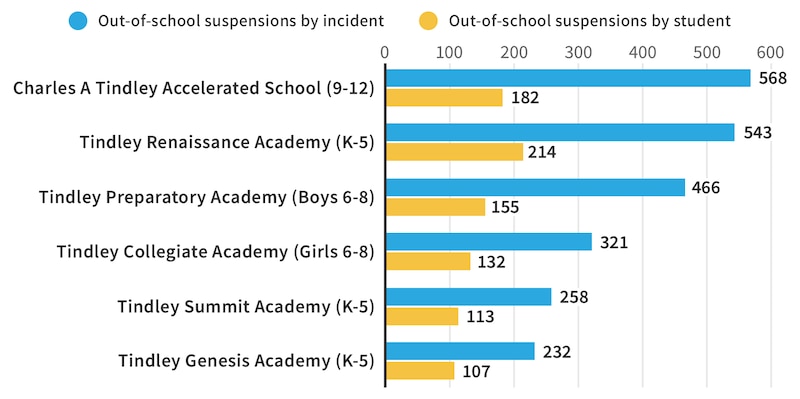

Tindley serves nearly all black students. Last year, roughly two out of every three students at Tindley’s high school were suspended from school at least once, according to state data. The school, which enrolled 273 students, reported 182 students receiving a total of 568 total suspensions.

None of the network’s six schools, including three elementary schools, recorded fewer than 100 suspensions. The highest rates were at the all-boys’ middle school.

Tindley, which enrolls about 1,700 students across the network, is trying to become more aligned with restorative justice practices and look more into what’s causing students’ problems, Marshall said. Any time students get into trouble, school officials will call families in for conferences.

“What we’re trying to do is bring parents into the consequences before we [take students] out of school,” she said.

Sometimes, she thinks discipline issues arise out of students not being accustomed to the fast pace of Tindley’s curriculum — and then suspending them from school leads students to fall further behind. “It’s proven more effective to put that time into instruction,” she said.

The changes could also push teachers to improve their relationships with students and develop classroom management skills instead of resorting to suspensions, Marshall said.

The shift away from automatic suspensions is a dramatic turn for Tindley, which was an early charter school choice in an underserved, impoverished neighborhood — and, with test scores climbing to be among the best in the city, one of the first to show high achievement among its predominantly black students, many of whom come from lower-income families.

The high school distinguished itself with high expectations and long school days. The school’s front hallway is lined with years of college acceptance letters, with its motto painted in enormous letters: “COLLEGE OR DIE.” In the early years, founder Marcus Robinson explained that while the motto may sound extreme to some people, he felt passionately that it was in fact the reality for many of Tindley’s families. Education, he believed, could be a way out of the crime, drugs, and poverty surrounding them.

Stringent rules were put into place to eliminate classroom disruptions, create a safe environment for students, and establish a baseline of expectations for students coming in from often-troubled schools, officials said.

In 2012, Tindley took its controversial discipline tactics to Arlington High School, a chronically failing school in IPS taken over by the state and handed to Tindley, then known as EdPower, to turn around. While some, including Craig, criticized the high suspension rates that followed, some students said the strategy made the chaotic school feel safer under Tindley’s management, which ended in 2015.

Robinson stepped down from Tindley in 2016 amid scrutiny over his lavish spending at the network’s expense, which exposed broader financial problems within the network. That led to the hiring of Marshall, a former Tindley middle school principal tasked with stabilizing the network.

The kinder, gentler approach to discipline is being explored elsewhere in Indianapolis. At KIPP Indy, part of a national network of schools that also started with a “no excuses” philosophy, schools have started incorporating programs for mentoring, peer mediation, and “holistic social-emotional learning,” executive director Emily Pelino Burton wrote in an email.

“Again, maximizing learning time by keeping our students in the classroom is incredibly important to us,” she wrote.

KIPP Indy recorded 678 out-of-school suspensions last year at its middle school of about 300 students, according to state data.

Indianapolis Public Schools has also taken steps to reduce out-of-school suspensions, though some worry that the sole focus on lowering those numbers could create unsafe school environments because staff might downplay dangerous behavior.

La Wanda Girton, whose son ended up with a one-day suspension after the pencil incident, admits, “I almost have a double standard,” because she chose Tindley in part because of its strict discipline. She values the safe environment and doesn’t want her three children in classrooms where other students fight or throw chairs. But at the same time, she thinks Tindley needed to relax its rules to make school more “reasonable” and “doable” for students.

“I am a Tindley advocate,” Girton said, “but when I would talk to parents about their children being there, as a parent, I’m saying to people, it’s a great school — but it’s very strict discipline-wise. I felt the need as a parent to put that caveat there, because I didn’t want to set people up for failure.”

For her three children, the strict rules have largely not been an issue, she said, with only a couple of isolated incidents, and they have thrived under “the Tindley way.” Girton, who is on Tindley’s parent council, is excited that the discipline changes could make the schools more attractive to other families.

Marshall said she doesn’t expect the changes to erode Tindley’s distinctive culture. Consider, she said, that when the high school began piloting the changes and announced that male students — gentlemen, in Tindley parlance — were no longer restricted to short haircuts, a student double-checked with her before getting his hair done, to make sure he wouldn’t get in trouble for showing up with braids and a fade.

On a recent morning, as students arrived before class, they walked into the multipurpose room, where the new rules let them play on their phones and talk before class.

It’s not loud, not like school cafeterias can be, but for principal Marlon Llewellyn, this is a big difference.

“This would’ve been completely silent,” he said. “Girls on one side, boys on the other. No devices.”

But when it’s time for school to start, Llewellyn takes a few steps toward the middle of the room with one hand raised — and within seconds, the room falls completely quiet. Silenced phones disappear into backpacks as classes file out one by one.

Two student ambassadors stay to talk about the discipline changes and how Tindley’s structure and fast pace have prepared them for real jobs. One shaved off his dreadlocks to attend Tindley schools. They wear what they consider ugly, plain shoes every day because that’s the dress code, along with neatly tucked-in polo shirts, sweater vests, and khakis.

They can recite the punishments for misconduct from memory. Horseplay: three days’ suspension. Profanity: 10 days.

Taran Richardson, 16, a sophomore, mentions having been suspended for being involved in horseplay — even when it wasn’t his fault.

“Guilty by association,” fellow sophomore Dajour Finley said, nodding solemnly.

“You’re sending us out of the school with a suspension, so you’re not learning,” Taran said. “They can still discipline us in a decent way and still allow us to receive an education.”

But they also talk about how Tindley is more than the rules — how teachers can see if a student is having a tough day, and might ask what’s going on instead of deeming it insubordination.

“I always thought it was the people that made up Tindley — the staff and students connecting with one another, and striving for success,” Taran said.