As Indianapolis Public Schools leaders prepare to ask voters for more money, they are considering a dramatic move: Selling the district’s downtown headquarters.

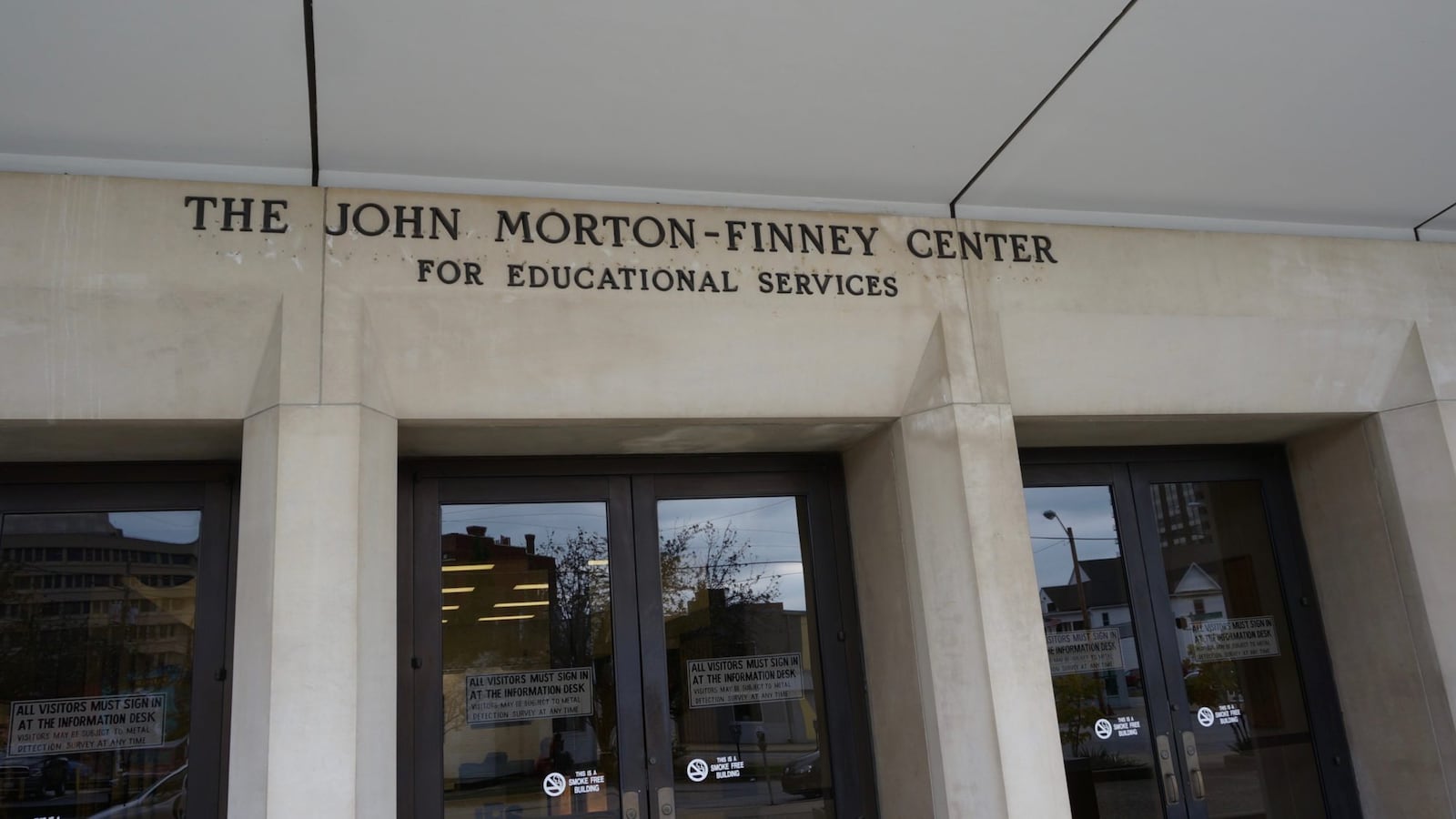

The administration is exploring the sale of its building at 120 E. Walnut St., which has housed the district’s central office since 1960, according to Superintendent Lewis Ferebee.

Although architecturally dated, the concrete building has location in its favor. It sits on a 1.7-acre lot, just blocks from the Central Library, the cultural trail, and new development.

A sale could prove lucrative for the cash-strapped Indianapolis Public Schools, which is facing a $45 million budget deficit next school year.

A decision to sell the property could also convince voters, who are being asked to approve property taxes hikes in November, that the district is doing all it can to raise money. Two referendums to generate additional revenue for schools are expected to be on the ballot.

“IPS has been very committed and aggressive to its efforts to right-sizing and being good stewards to taxpayers dollars,” Ferebee said. “Hopefully, that [will] provide much confidence to taxpayers that when they are making investments into IPS, they are strong investments.”

Before going to taxpayers for more money, the district has “exhausted most options for generating revenue,” Ferebee added.

The administration is selling property to shrink the physical footprint of a district where enrollment has declined for decades. The number of students peaked at nearly 109,000 late-1960s. This past academic year, enrollment was 31,000.

During Ferebee’s tenure, officials say Indianapolis Public Schools has shrunk its central office spending. But the district continues to face longstanding criticism over the expense of its administrative staff at a time when school budgets are tight.

Ferebee’s administration has been selling underused buildings since late 2015, including the former Coca-Cola bottling plant on Mass. Ave., and at least three former school campuses. Selling those buildings has both cut maintenance costs and generated revenue. By the end of this year, officials expect to have sold 10 properties and raised nearly $21 million.

But the district is also embroiled in a more complicated real estate deal. After closing Broad Ripple High School, the district wants to sell the property. But state law requires that charter schools get first dibs on the building, and two charter high schools recently floated a joint proposal to purchase the building.

The prospect of selling the central office raises a significant challenge: If the building were sold, the district would either need to make a deal for office space at the site or find a new location for its employees who work there. Ferebee said the district is open to moving these staffers, so long as the new location is centrally located, and therefore accessible to families from all around the district.

It will likely be months before the district decides whether or not to sell the property. The process will begin in late July or early August when the district invites developers to submit proposals for the property, but not a financial bid, according to Abbe Hohmann, a commercial real estate consultant who has been helping the district sell property since 2014.

Once the district sees developers’ ideas, leaders will make a decision about whether or not to sell the building. If it decides to move forward, it would proceed with a more formal process of a request for bids, and could make a decision on a bid in early 2019, Hohmann said.

Hohmann did not provide an estimate of how much the central office building could fetch. But when it comes to other sales, the district has “far exceeded our expectations,” she said. “We’ve had a great response from the development community.”