If you’re a millennial, baby boomer, or something in-between, chances are you learned how to multiply fractions — and it was pretty easy.

Numerator times numerator, denominator times denominator — boom. Answer. One-half times one-half is one-fourth. Two-thirds times one-third is two-ninths. You barely need to think about it.

But why does that trick work? If you’ve perused the internet in the age of Common Core math memes, or have children who are subject to new types of teaching, this question has probably crossed your mind. Students today are expected to know why calculations work, not just how to get an answer. Part of that is rooted in the academic standards adopted by Indiana and other states in recent years that focus on critical-thinking, problem-solving, and understanding the concepts behind the content.

The problem? There are still educators who aren’t up to speed on the new approach, and observers say schools haven’t made training a priority. At the same time, the metrics that Indiana and the federal government rely on most — ISTEP test scores, graduation rates, A-F grades, or scores on “The Nation’s Report Card” test — aren’t showing that students are learning more under the new model, despite years of controversial reforms centered around school choice and major testing, standards, and accountability overhauls aimed at improving student achievement.

Math is just one of the areas where state standards don’t necessarily match instruction in the classroom — but a group at the Indianapolis-based non-profit The Mind Trust want to help schools bridge that divide. Joe White, who directs school support initiatives for The Mind Trust, and his team received grant funding to put on free educator trainings with Nashville-based Instruction Partners that are designed to help schools better implement the changes to Indiana’s academic standards.

Read: Shorter, faster, smarter: How officials say Indiana’s new ILEARN test could differ from ISTEP

White believes without a greater focus on instruction and standards — how students learn, how teachers teach, and what the state expects students to know — Indiana can’t expect to get out of its academic rut. Since 2015, statewide ISTEP passing rates have barely budged from a little over 50 percent, and graduation rates have only changed by about one percentage point up or down since 2011.

“The root of what we attribute to that stagnation, I think it starts with the standards,” White said. “We can do the really shiny, glossy, sexy things, but if we don’t have this right, none of it’s going to matter.”

The standards were adopted more than four years ago after the state abandoned Common Core. Now — after other big policy debates have died down — the focus on the classroom can begin, a strategy supported by national advocates as well. Mike Petrilli, executive director of the conservative-leaning Fordham Foundation, said for Indiana to improve like it did on national exams from 2011 through 2015, this is a natural next step.

“How do we make sure that teachers are actually implementing the standards that are set?” Petrilli said. “Is there a way to offer more assistance to local school districts to make sure they are using high-quality materials? … If you want to improve teaching and learning, then let’s focus on what is being taught in the classroom.”

The idea behind the teacher trainings is fairly straightforward: Students do better academically when they have access to high-quality curriculum taught by teachers who know what the state expects students to learn and how to teach it. And that begins with academic standards.

But in a lot of schools, White said, the change in standards hasn’t necessarily produced better outcomes for students. He’s observed low-quality curriculum and student work that isn’t aligned with state expectations, and school leaders are too often focused on school culture. That’s important, he said, but instruction should be the priority.

“A building can look and feel healthy from a cultural standpoint, but we shouldn’t pursue culture at the expense of rigor,” White said. “It’s a difficult thing.”

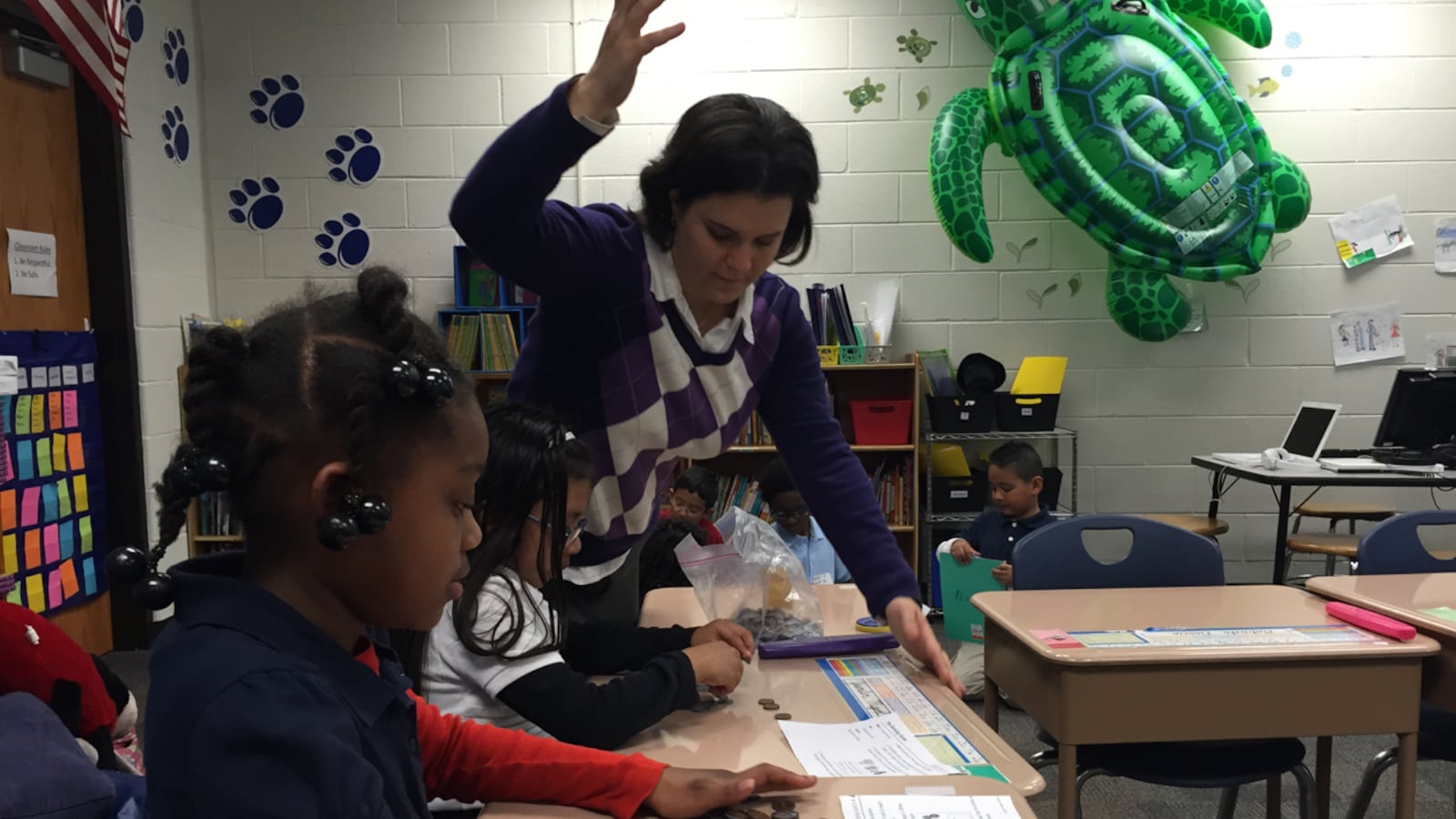

Jessica Kohlmeyer, director of student affairs for United Schools of Indianapolis, a network of mayor-sponsored charter schools that includes Avondale Meadows Academy, and her staff have spent the past year attending the standards trainings put on by The Mind Trust and Instruction Partners, as well as another in California earlier in the year. The work has opened her eyes, especially when it comes to how to support teachers.

Her whole leadership team has received training on the standards now so they know what to look for in classrooms and how to, in turn, train teachers as they head into the next school year. They’ve already had several days of training for staff since school ended, and they plan to continue it.

Previously, Kohlmeyer said, teachers created their own lessons from scratch. Grade levels would divide and conquer based on who had the most expertise in each subject. Not only did that mean that certain teachers never got a chance to dig into other subject areas, but it also meant the teachers with the most knowledge in one area had students do better in those areas — where teachers were deficient, students were also more likely to be deficient.

“We were asking teachers to create material, which is asking a lot of a person,” she said. “You have to not only know the standards well, you have to know all the standards well and have time to build the lessons … but a third grade teacher is not trained or built to write curriculum for third grade.”

And as the charter network has piloted new curriculum and started to spread its standards trainings over the spring and summer, teachers have been largely on board, Kohlmeyer said. Many of them realize they were taught certain things, such as subtraction or multiplication, a different way than they are teaching students now, but they’re open to learning the new concepts and working them into their lessons.

“Teachers have always been working hard, that has never been a question, but have they been focused on the detail of the standards?” she said. “That’s where we’re going to see a difference in the language and the conversations in the class.”

Kohlmeyer said when the standards were switched four years ago, she was a teacher. At the time, her school did a standards training, but it was more about letting educators know how the content had changed — that a topic was moving from fourth grade to third grade, for instance — and not really about how teaching needs to be adjusted to better meet the new expectations.

There are three levels to rigorous instruction, said presenters from Instruction Partners: Conceptual, procedural, and application. And each academic standard could require teaching at at one, two, or all three of those levels. The trainings were open to teachers and administrators, and featured workshops divided by grade level and subject. Elementary math teachers would gather together to learn during some of the sessions, and school leaders had other sessions focused on building capacity with staff and creating a vision for how an entire school’s instructional practices might change.

For example, if a standard requires students to understand subtraction, the concept is explaining place value and what happens to numbers when you remove parts from them. The procedure is the written steps to subtraction you might have learned in school — stacking the numbers on top of one another and subtracting vertically, maybe “carrying the one” until you arrive at an answer.

Usually, it’s easy to teach the procedure — but that doesn’t go deep enough for students to actually understand how subtraction works and why. To teach most effectively, teachers and administrators have to be able to recognize when student work is reaching each of the three levels, and when that’s appropriate for the standard being taught, or not.

But instruction, in and of itself, isn’t the only factor in student achievement or growth, Teresa Meredith, president of the Indiana State Teachers Association, said. She questions whether the lack of growth and improvement in student performance should be attributed solely to teachers’ training.

“I don’t see (changing instruction) as a big magic bullet that’s going to suddenly make everything jump up and scores rise,” Meredith said. “You also have to look at the student.”

Meredith questions whether the new standards and the amount of testing in schools is developmentally appropriate for young children, questions that have been echoed repeatedly over the past decade. She also said she’s heard from her members that they want more feedback on how they doing — not just a score on an evaluation that too often feels punitive, she said.

“Teachers, they want to know that they’re doing a good job, so it’s nice when an administrator says ‘Hey, good job!’” she said. “But what does that quantify to, and what does that look like, and how can I become better than that?”

And at Avondale Meadows, Kohlmeyer said she wants to focus on how she and her staff can support teachers so they can get the feedback they need to improve and, in turn, help students grow, too.

“These shifts (in the standards) are not new,” Kohlmeyer said. “The problem is there hasn’t been any development around them. To me, that was a teachable moment. We know they’re not new, but what is new to us is the focus we’re putting on them.”