Back when she was principal of the KIPP middle school in Indianapolis six years ago, Aleesia Johnson was about to head out one evening when she heard something that made her stop. Her assistant principal, Andrea Minich, was in the middle of a difficult call with a mother upset about how her child was disciplined — and it wasn’t going well.

So instead of leaving, Johnson stayed in the office until about 10:30 p.m., Minich recalled. Johnson passed Minich notes with advice, encouraging her to be less defensive, to breathe, and to listen to the mother’s concerns.

At the end of the phone call, Minich said she and the mother still disagreed, but the parent was calm.

“I was still relatively young at that point in time, and it definitely could’ve been a moment that really broke me,” she said. “But she used that to really build me up.”

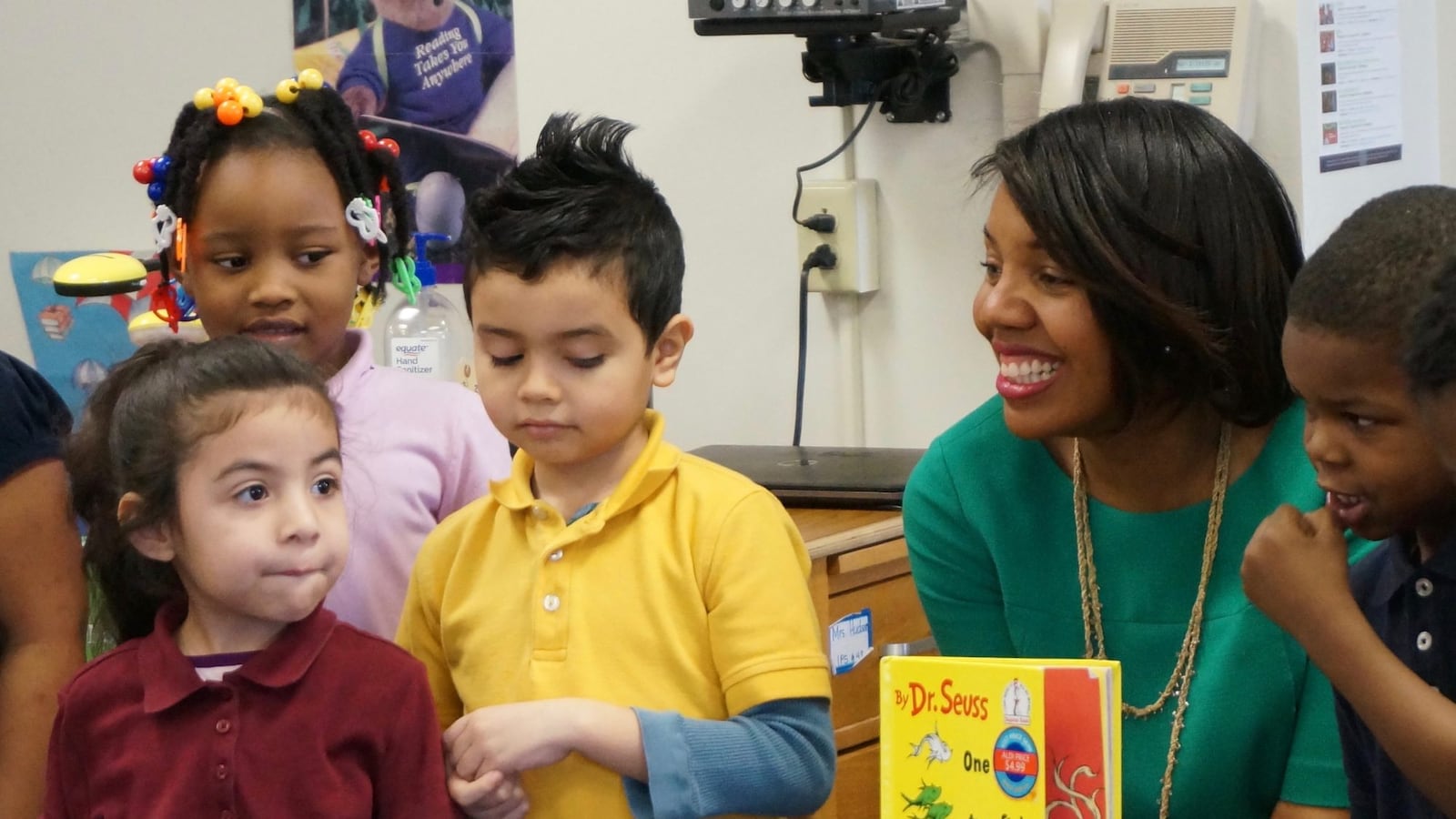

This willingness to listen, including to critics, and a deep investment in helping colleagues grow are among the strengths that supporters say Johnson, 40, brings to her role leading Indianapolis Public Schools and could be assets if she secures the position permanently.

Johnson took over the district on an interim basis in January, after former Superintendent Lewis Ferebee left for Washington, D.C. As Ferebee’s deputy superintendent, Johnson is a favorite of several influential Indianapolis leaders to take the helm permanently of the state’s largest school district, even before any candidates have thrown their hats into the ring.

Those who knew Johnson in previous roles say that while, like Ferebee, she has not led a district, she has many of the qualities that would help her succeed as superintendent: empathy, grace under pressure, and the ability to make tough decisions. She listens to critics and handles conflict deftly, they say — traits that could be powerful in Indianapolis Public Schools, where Ferebee faced persistent criticism that his administration was not engaging families early enough on tough decisions or responding to feedback.

But amid that anger and distrust, someone closely associated with the district’s controversial changes like Johnson could struggle to win over critics. Much of her 15 years working in Indianapolis education were at a charter school and the school reform-aligned Teach For America. She is still relatively unknown among some parents, teachers, and advocates.

And critics argue that building strong relationships is not enough considering the challenges the district faces. Although Indianapolis Public Schools won an influx of funding from voters last fall, it is still facing massive cuts — including likely school closures — so it can spend more on priorities such as teacher pay. At the same time, passing rates on state tests remain persistently low, particularly for students of color and students from low-income families.

“She’s personable. She’s approachable,” said Jim Grim, a frequent critic of Ferebee’s administration who leads community school partnerships at IUPUI. “Those are good qualities, I’m not saying they are not. But those aren’t the only qualities we need.”

Johnson’s mother and grandfather were educators in traditional public schools, but she took a different route. After earning a master’s degree in social work, she began teaching in New Jersey through Teach For America. In Indianapolis, she worked at both Teach For America and KIPP Indy, where she led the middle school for three years before joining Indianapolis Public Schools.

A native of Evansville, Johnson, who attended private school, said she works in education because she believes families should have access to the same kind of high-quality education she had. As a black woman, she is keenly aware of the systemic issues facing black and brown children, she said.

“I was very fortunate to have a great education,” Johnson said in an interview with Chalkbeat last month. “I just feel this incredible sort of responsibility to my community.”

Her route to the top of Indianapolis Public Schools was unconventional, but it reflects the transformation of the school system into one where the line between traditional and charter schools is blurred. Since 2015, the district has created 20 “innovation schools,” which are considered part of Indianapolis Public Schools but are run by outside operators, primarily charter networks. And even at schools that are still run by the district, principals have gotten increasing freedom.

Johnson has been instrumental in that change. She joined Indianapolis Public Schools nearly four years ago to oversee the new innovation schools, and she helped define the contours of the program — from how to engage families at schools that might be overhauled to the details of contracts with the operators.

The central office still has a role to play in supporting principals and helping them become better leaders, Johnson said. But she believes in the mission of giving principals more control over their schools.

“They know their families and students deeply. They know their staff,” she said. “They need the space to be able to make decisions that are going to be in the best interest of all of those people.”

Likely because of Johnson’s work in Ferebee’s administration, there is substantial opposition to choosing her as the next superintendent from critics of the district’s direction, such as the IPS Community Coalition. The group came out with a statement in January that described Johnson’s experience and qualifications as “lacking.”

Chrissy Smith, one of the leaders of the coalition, said Johnson’s work with innovation schools is “troubling,” because she does not want the district to continue that approach, and she has concerns about the process of creating the schools. The meetings at traditional schools facing the prospect of conversion to innovation status were “always rushed” and didn’t involve the community as much as they should have, she said.

Based on that experience, Smith said, “I don’t have hope” that Johnson will be able to work with critics.

Johnson is aware she is stepping in at a time when there is organized opposition to changes in the district and vehement disagreement over the best way to improve education.

“I believe we all agree on, we want a great system for kids — we want great schools for kids,” Johnson said. “We can disagree respectfully on the ‘how.’ And I think we can struggle through that in a way that can ultimately be productive. … If people are willing to come to the table sort of open to what can be possible.”

As interim superintendent, Johnson, who is paid $222,380, presides over a district of about 31,000 students, including those at charter schools under district oversight. There’s a political side to the job, and she spends a fair amount of time meeting with community leaders and, especially during the legislative session, talking to lawmakers, she said. But she also oversees what’s happening in schools, spending time with school principals and academic staff.

At about 7:30 a.m., Johnson starts each day by dropping her three children off at a district school. Then, she heads to the gym or into the office, where she is often one of the first to arrive. If she’s picking her children up from school, she leaves before 6 p.m., but other days she spends her evenings at school board or community meetings.

Even before Johnson joined Indianapolis Public Schools, she worked long hours, her former colleagues say. At KIPP, she would work a full day and leave to pick up her children, only to return with her whole family for a school barbeque or basketball game.

“She definitely worked ridiculous amounts of hours for our kids, while still somehow managing to be an amazing mom, which I think was something that always astounded me,” said Emily Pelino Burton, superintendent for KIPP Indy.

The close relationships Johnson developed are evident in the stories students, parents, and colleagues tell about her.

When Nyree Modisette started at KIPP Indy’s middle school in eighth grade, she was so far behind that an assessment put her at about a second-grade reading level. Johnson and other educators at the school went back to the basics, staying after school to tutor her on phonics and making sure she had her favorite books, like those by Judy Blume, said Modisette. By the end of the year, she was on grade level and heading to Brebeuf High School.

“It was remarkable. I will never forget that — how they took that time out to actually help,” said Modisette, who is now a senior at Butler University and still keeps in touch with Johnson. “I wouldn’t be where I am today if it wasn’t for their help.”

Nyree Modisette’s mother, Roshawn, met Johnson when her daughters enrolled in KIPP, but she eventually took a job as a special education assistant, her first “professional” job, she said. Initially, she felt insecure because she was a single mother who hadn’t graduated from college.

But that changed after a meeting at the school when Roshawn Modisette was too afraid to respond as a parent yelled at her.

“Aleesia told me, ‘I’m gonna teach you how to use your words,’ ” said Roshawn Modisette, who began leaning on her experience as a mother as a source of authority. “What she taught me was confidence.”

Colleagues say Johnson holds students and employees to a high standard. But she is consistently kind. Even in tough situations, dealing with middle schoolers or irate parents, she keeps her cool and never gets visibly angry.

“I’ve never seen her upset. It used to make me nervous,” said Roshawn Modisette, who now laughs about it. “She’s always so calm.”