Some education advocates are decrying Indiana’s strategy for closing gaps in test scores and graduation rates among students of color, criticizing the state for setting lower expectations for black and Hispanic students.

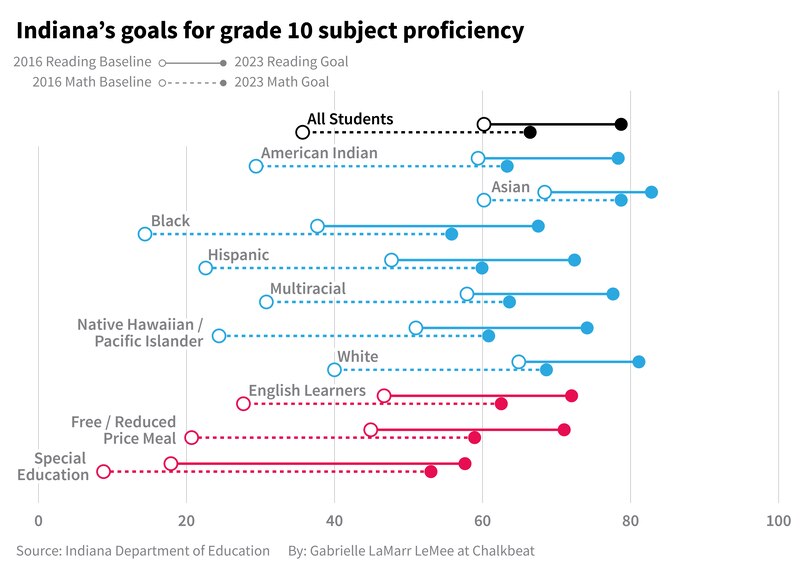

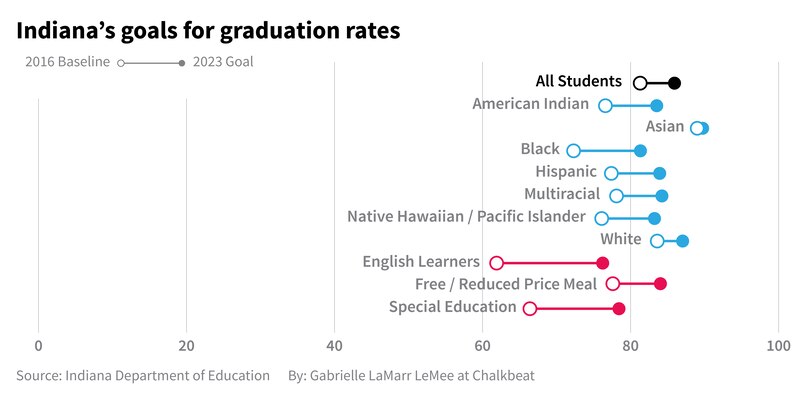

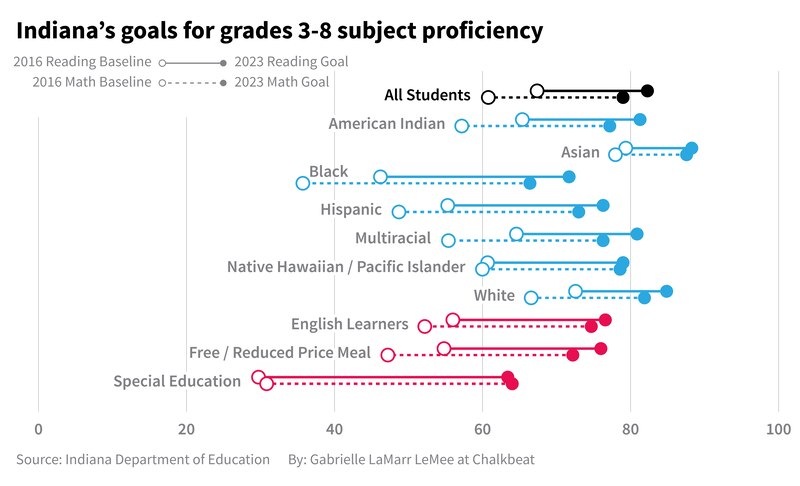

The state’s five-year goal is to cut in half the number of students who aren’t passing tests or aren’t graduating from high school. But because officials have set targets for each racial group based on how they’re performing now, the state’s goals won’t completely close gaps between students of color and their white peers.

“Oftentimes in the African-American community, we talk about the fact that systems are set up for our children to fail, and this looks a lot like that,” said IUPUI lecturer and civil rights advocate Marshawn Wolley. “You’re essentially saying with these goals that you’re going to have a segregated educational system. You’re going to have segregated outcomes.”

The state’s target for black students, for example, is for about three out of four students to pass language arts and two out of three students to pass math in the elementary and middle school state tests by 2023.

Because black students are the farthest behind on test scores, hitting their targets would require bigger jump than for every other racial group. But the target would still put black students behind white students, who are working toward a goal of having more than 80 percent pass the tests. And it would put black students behind the state’s target for overall student performance.

Wolley criticized the approach in a recent column for the Indianapolis Business Journal, one of two opinion pieces that published over the weekend reigniting a debate that has waged both locally and nationally over improving academic outcomes among students of color.

Advocates say the state is sending a message that officials don’t think black and Hispanic students can reach the same levels of achievement as white and Asian students. That mindset, they say, won’t close the persistent disparities in how schools serve students of color.

But the state education department counters that its approach is “rooted in equity” and expects all racial groups to get 50 percent closer to all students passing tests or graduating, while taking into account where they are now.

“In order to close such gaps, we first must acknowledge there is an issue,” Indiana Department of Education spokesman Adam Baker said in a written statement. “From there we look at where students are and establish goals that are ambitious yet achievable given these starting points.”

Many states use a similar tactic of setting differentiated goals, but some set the same goals for students of all races, according to Education Week’s tracker of trends in states’ education plans.

Setting the same goal for all racial groups “does a disservice to both struggling students and high-achieving students alike,” state officials wrote in Indiana’s plan for complying with the federal Every Student Succeeds Act.

Indiana has largely struggled to make significant strides in improving educational outcomes for black students in particular, showing little gains in test scores in recent years. Test score gaps are widening between black students and white students. Nearly a third of Indiana schools receive failing marks for how they serve black students, compared to 2 percent of schools failing to serve white students. And the state has been criticized for not doing enough to make sure schools are serving students of color as well as they serve white students.

Sekou Biddle, UNCF’s vice president for advocacy, said the state’s stance on racial gaps reveals critical blind spots.

“People have to consider: If we were talking about your children, would you be in the camp of, ‘We need to be realistic and reasonable in the expectations’?” Biddle said. “I don’t think so. I’ve never heard a parent tell me, ‘Oh, you know, I would be OK with my kid doing less well, because, you know, it’s hard.’”

Advocates say they worry that serving students of color is not a high enough priority for the state. This debate, they say, underscores the need to tackle these gaps — and what’s needed to effectively close them, such as more funding, more wraparound services, and more lessons that reflect and include people of color and diverse cultures.

The issue also highlights a need to dispel common assumptions that students of color come from poverty, and that poverty is too big of a problem to overcome, said Carole Craig, an education consultant and former education chairwoman for the Indianapolis NAACP.

If you believe all children can learn, and if you want to help who have fallen behind, she said, “then you do everything you can to move them forward, so they can catch up.”