Indiana Senate Republicans are proposing a $535 million increase in school funding through 2021, a larger boost than the House’s plan, according to a budget draft released Thursday.

The Senate budget would also earmark about $694 million to help educate children in poverty in 2021, according to lawmakers, an issue that has drawn attention in recent weeks. That’s lower than the current overall funding level, due to a drop in the projected number of students who qualify for poverty aid, lawmakers say. But it’s more generous than the House’s March proposal, which would make controversial and significant cuts.

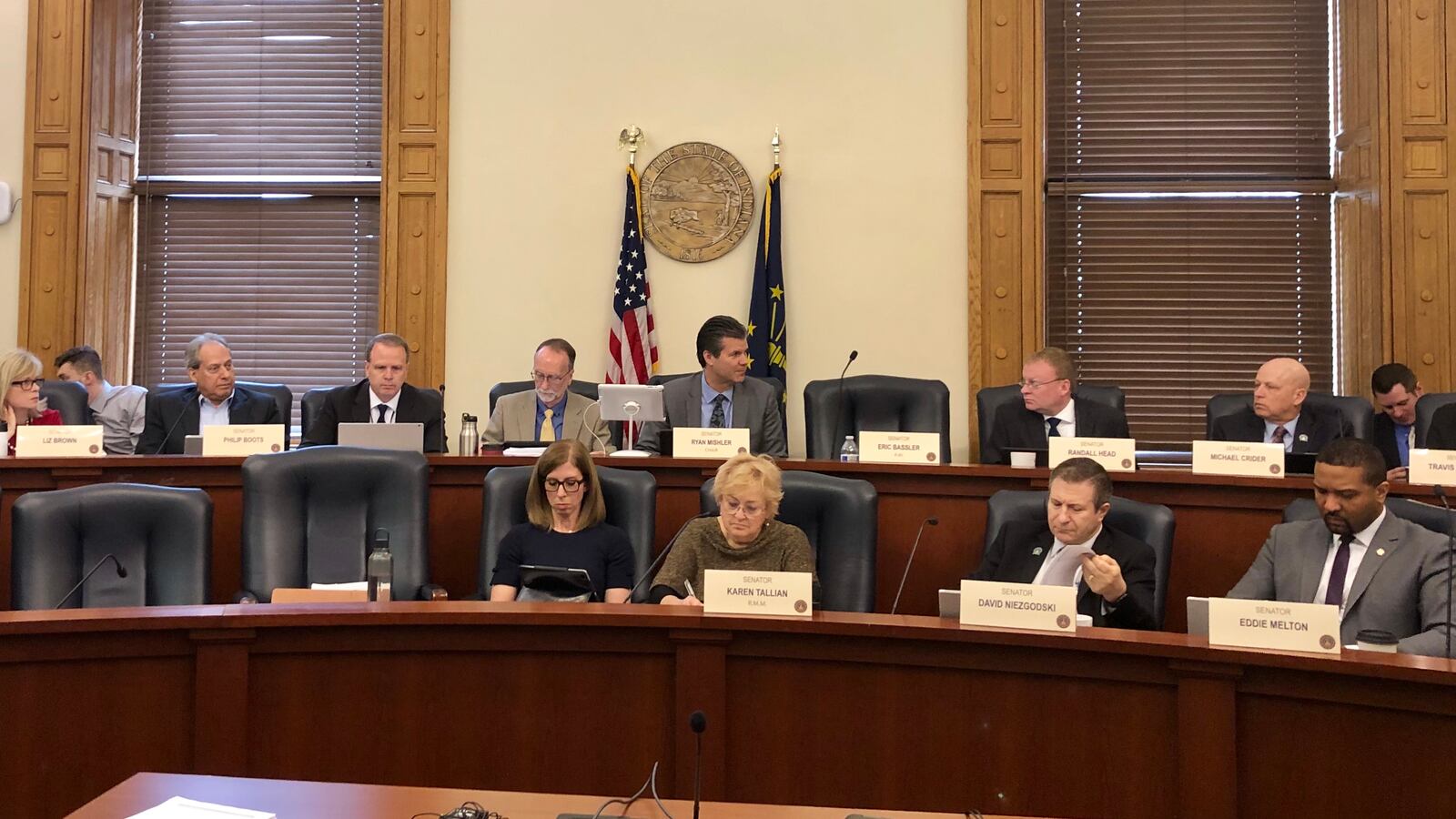

Under the Senate budget unveiled Thursday, the per-student amount districts receive for educating high-need children increases by $255, reaching $3,794 in 2021, said Republican Sen. Eric Bassler, chairman of Senate school funding subcommittee.

Senate leaders said the boost in per-student poverty aid aims to cushion funding losses for high-poverty districts compared with the House budget.

“I think that’s a reasonable short-term solution to the challenge,” Bassler said.

Total funding for schools would reach $14.9 billion over two years, under the plan. The Senate’s 4.9 percent education spending increase is a little more than increases in years past and slightly higher than the House’s proposed 4.3 percent increase. The basic per-student funding that all districts get would jump from $5,352 per student this year to $5,586 per student in 2020 and $5,692 per student in 2021.

The Senate budget also would increase funding for students who are learning English to $22.5 million annually, compared to $17.5 million this year. The amount districts get for those students would vary based on how fluent they are.

Overall, the budget received a muted reception from education advocates.

Ahmed Young, the chief of staff for Indianapolis Public Schools, described the Senate budget as “a step in the right direction,” highlighting increased funding for areas including English language learners.

“They are beginning to understand and quantify the cost that it takes to address issues of poverty,” Young said.

The Senate budget is “definitely better than the second version from the House,” said David Marcotte, executive director of the Indiana Urban Schools Association. But he is still concerned about the potential cuts to the poverty aid districts receive.

“We’re just not seeing less poverty in our schools,” he said. “We still have a lot of children with significant needs.”

The proposed cuts would be the latest in a series of reductions that have already lowered poverty aid by 30 percent since 2015. In the past, Indiana relied on whether students are eligible for free or reduced-price lunch to measure need. But in 2015, state lawmakers decided to shift to using the number of students who receive food stamps, welfare, or are in foster care. The new measure of need includes a narrower — and poorer — group of students.

Bassler said the legislature will look at new ways to measure poverty for future budgets, with the aim of stabilizing school funding and ensuring districts receive enough to educate students in poverty.

Last week Bassler told Chalkbeat that the Senate would consider adding students who receive Medicaid to the formula that determines poverty aid. But the Senate ultimately did not include that measure. Bassler said Thursday that when staff did projections, adding students on Medicaid to the calculations did not benefit urban districts.

The Senate budget does not specifically increase pay for Indiana teachers, an issue that has gotten national attention. It does increase the amount of money for teacher bonuses, which go to teachers who are rated effective or highly effective on their evaluations. The budget includes $90 million over two years for those grants, which is distributed to districts based on their enrollment. Districts would be allowed to add up to half of the stipends to teacher base salaries.

Lawmakers have said that they can’t direct districts to pay teachers a certain amount without taking away their control to bargain and negotiate locally. However, in the Senate’s proposal to take $150 million from the state’s pension stabilization fund to pay down schools’ teacher pension liability, they do require school boards to hold a public meeting to discuss how they spend the savings.

Lawmakers in the House and Senate will ultimately have to come to a compromise between the versions before session ends in three weeks.