As soon as Alina Keller walked into the home daycare, she wondered whether her son would be safe if she sent him there, let alone prepared for kindergarten next year.

For $100 per week, the daycare would downgrade 5-year-old Liam to using a sippy cup, put him down for three-hour naps, and leave him to play all day without any plans for teaching him letters or numbers, Keller said.

It was like “baby jail,” she said — “an absolute no-go and a nightmare.” But it was also one of her only options in her rural town of Goodland, Indiana.

“What am I supposed to do? I have to work to provide for my family, but at the same time, I have to make sure that my kid is safe,” said Keller, 32, a factory worker who lives about 100 miles northwest of Indianapolis.

Keller’s predicament is one facing many Indiana families five years into the state’s efforts to make early childhood education widely available: She lives in a preschool desert, in one of five counties with no early learning facilities nearby that the state considers to be high quality.

These gaps in access, paired with high tuition and low state investment, mean that whether your 3- or 4-year-old attends prekindergarten — and how good the experience is — can often largely depend on where you live and how much money you make.

Preschool can be a critical early intervention for children who have had less exposure to language and literacy. But there aren’t enough highly rated pre-K providers in the state to accommodate all 4-year-olds, officials say, with few or none in some rural pockets. And the price tag for a good preschool can be too high for lower-income families, whose children are more at risk of starting school behind their peers.

“A child is only 4 once, so each year that passes without families having the ability to put those children in pre-K is a huge lost opportunity,” said Ann Murtlow, president and CEO of the United Way of Central Indiana, a leading early learning advocate.

Indiana has taken some small steps to help its neediest families access pre-K, with lawmakers voting this year to open up the state’s $22 million fledgling pre-K program statewide.

But even with that change, Indiana has barely made a dent in improving early childhood access, advocates say: The income-based voucher program reaches just under 3,000 of what advocates estimate to be 27,000 4-year-olds from low-income families, with a rocky rollout that has left about 1,000 available spots unfilled.

“We’ve come a long way, but we should make no mistake that we still have a very long way to go,” Murtlow said.

The slow progress isn’t wholly unexpected in a state that lags the nation in early childhood education. Most states outpace Indiana in pre-K enrollment, with some — including Florida, Vermont, and Oklahoma, according to a national report — making pre-K available to all 4-year-old children.

But in Indiana, pre-K is quickly garnering support from community and corporate leaders who see it as an economic development strategy — offering a family benefit to working parents while also better preparing children who will become the future workforce.

Early childhood education matters, advocates say, in a state where people face longer odds for upward social mobility, where most adults don’t have an education beyond high school, and where stubborn socioeconomic and racial gaps persist throughout K-12, putting some students at enormous disadvantages.

A series of stories by Chalkbeat Indiana and IndyStar will examine the state of early childhood education in Indiana. Right now, our state is mulling a big question: How much, and how quickly, will Indiana invest in pre-K?

Pushing Indiana toward its first steps

A few years ago, Indiana was among a handful of states without a pre-K program, and some communities were growing impatient.

Deep in southern Indiana, the Harrison County Community Foundation had zeroed in on pre-K as a possible solution to the constant grant requests to help students who were falling behind in school.

“We didn’t know what else to do except to try to get these kids as good of a start as we could,” said now-retired foundation president and CEO Steve Gilliland.

So in 2013, the foundation started funding free pre-K for low-income families in Harrison County, calling it “Jump Start.”

Children experience critical brain development from birth through their early years, so pre-K at age 3 or 4 can help build a foundation for their learning — not just ABCs and 123s, but basic skills like how to follow directions, take turns, and listen.

Research has widely shown that quality pre-K can put children ahead in kindergarten and beyond. While some critics contend that the positive effects of pre-K wear off as students grow older, long-term studies of Perry Preschool in Michigan and the federal Head Start program have showed far-reaching benefits, such as participating children being more likely to graduate from high school and less likely to commit crimes.

In Harrison County, the results within the first year stunned observers. Full-day, quality pre-K closed cognitive gaps in language, pre-literacy, math, and quantitative reasoning skills for low-income students who started behind their peers, Indiana University Southeast researchers found, catching them up to be ready for kindergarten.

Even the expert analyzing the results found herself impressed, despite long knowing about the academic gains that pre-K could produce.

“Wow! You can do so much with just this one year,” said Melissa Fry, director of the IU Southeast Applied Research and Education Center. “I read research for a living, so it was a little strange I would have that reaction. But it’s exciting!”

In 2014, then-Gov. Mike Pence made it a top priority to create Indiana’s first pre-K program — a voucher program for low-income families to enroll their 4-year-olds at schools, centers, churches, or homes that meet certain standards. But state lawmakers reined in his vision, limiting the size of the pilot until a study could show the effects.

Still, the willingness of Indiana policymakers to provide any public funding for pre-K represented a seismic shift in thinking in this conservative state.

This year, the state program, known as On My Way Pre-K, has grown to serve nearly 3,000 children. But with $22 million in funding, it has room for many more. State officials have run into obstacles trying to expand the program’s reach in rural areas. They’re struggling to keep the application process simple and raise awareness of the opportunity among parents.

Families often worry first about finding an affordable preschool with openings near them with hours that work with their schedules, child care experts say, favoring references from friends and family. They might not be as familiar with the process the state uses to identify high-quality providers, or the vouchers that might be available to help them.

Republican Gov. Eric Holcomb says pre-K remains a key initiative, hoping to iron out issues this year and enroll more students to max out the money. Annual reports show students in On My Way Pre-K show stronger gains in language, literacy, and school readiness, and the state recently won a $7 million federal grant that will help plan a pre-K expansion.

Holcomb is “impatient” for wider expansion, and he said he hopes the success of On My Way Pre-K puts pressure on the state.

“I want to see a scale-up — not just a scale-out to all 92 counties statewide, but a scale-up — to be able to meet the needs of our children that are taking literally their first steps on their education path,” Holcomb told Chalkbeat.

In Indianapolis, businesses and philanthropies gave money in 2014 to supplement a city preschool program alongside the state’s that also serves 3-year-olds — to fill the need, prove the value of early learning, and spur the state to deepen its commitment.

And pre-K is popular: Nearly 7,000 Indianapolis families applied this year, said Sara VanSlambrook, chief impact officer for the United Way of Central Indiana.

“That’s why we need to keep advocating for expanding pre-K,” she said, “because there continues to be more demand than there are seats.”

For many families, On My Way Pre-K offered an opportunity they wouldn’t otherwise have been able to afford, the reports say, and allowed parents to start new jobs, go back to school, or work more hours.

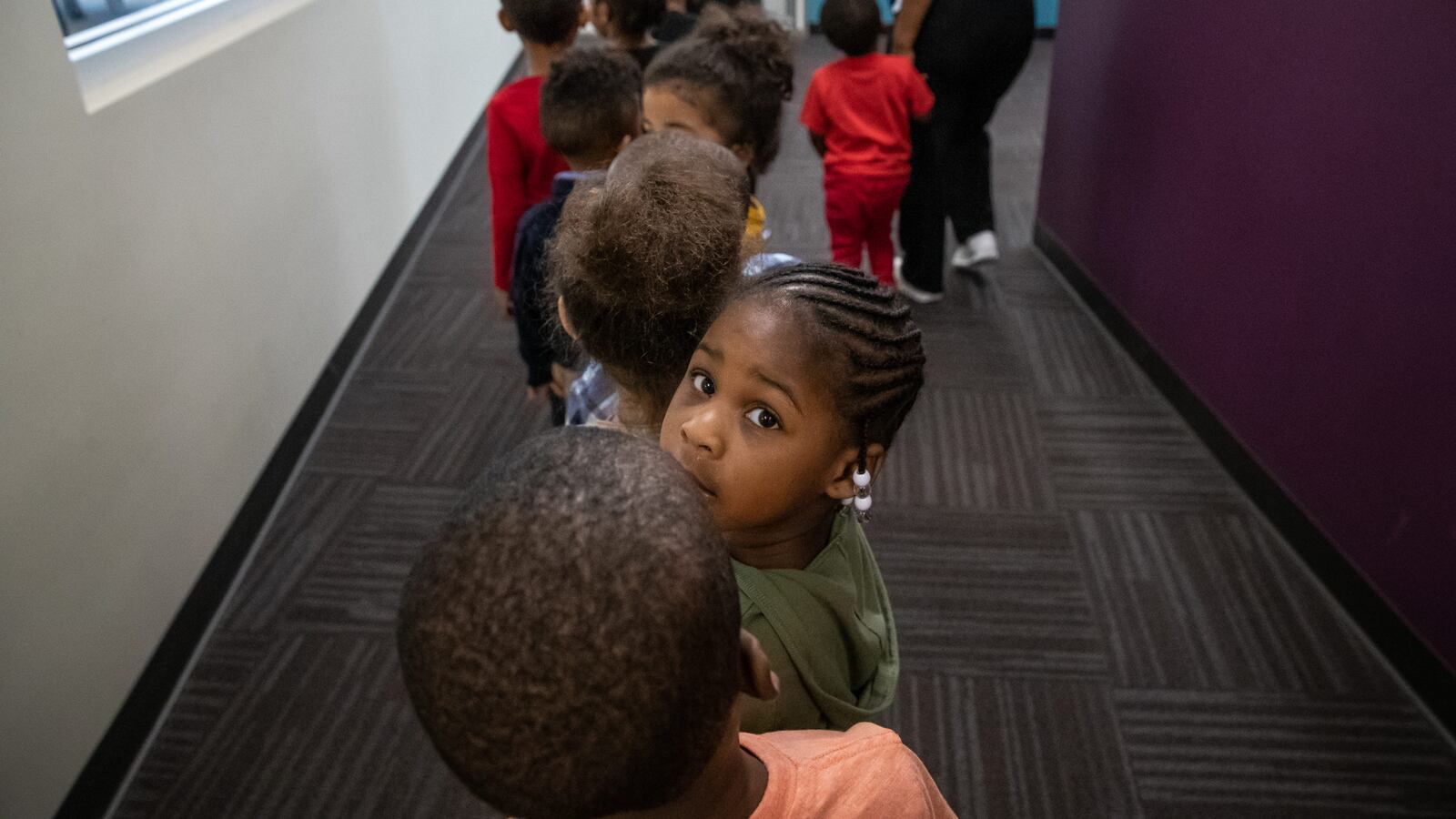

Natasha Williams, 32, a fast-food worker in Indianapolis, uses the pre-K voucher for her daughter, Zakoya, to attend pre-K at the Early Learning Center at the Avondale Meadows YMCA. Without the voucher, which pays up to $6,800 for pre-K fees, Williams said she would have had to work two jobs to afford preschool, which would have kept her from spending time with her children and pursuing her own education in human resources management.

In less than a year, Zakoya has become a loquacious 5-year-old who can spell her name and recite colors and shapes — scoring above-average, her mother said, on kindergarten readiness tests.

“Before, she was in daycare, where she played with toys,” Williams said. “Now she’s talking, developing conversations, saying, ‘I want to read books,’ and teaching her little sister what she learned.”

A frugal state mulls the costs

But what’s the state’s responsibility for providing pre-K?

Some conservative lawmakers balk at the idea that the government should pay for preschool. Rep. Tim Wesco, R-Osceola, said he hews to the “classic conservative Republican view” that families should take responsibility for their children’s early education.

“Parents need to be engaged in a regular, very consequential way in their kids’ education,” Wesco said, adding, “I just have general concerns about the state taking on that additional responsibility when we struggle already to cover K-12. I feel like the state is very quickly moving toward universal pre-K, and that’s where I am not on board with it.”

In some ways, Wesco is working against the tide — On My Way Pre-K enjoys hearty bipartisan support. But attitudes like his could prevail because money is likely to be a sticking point, if not a blockade to expanding pre-K. In a frugal state, lawmakers are cautious about unlocking sizable funds like the millions of dollars that would be needed to serve more children.

“We are a state that measures, that thinks, that contemplates: Where can we invest?” said Betsy Delgado, chairwoman of the Indiana Early Learning Advisory Committee and vice president of mission and education initiatives for Goodwill of Central and Southern Indiana.

The state already combines pre-K funding with federal money to stretch its dollars. Recognizing the difficulty in getting dedicated state dollars outright, advocates have started to float a few creative ideas for funding pre-K, such as using revenue from food, beverage, or cigarette taxes, or seeking private donations.

There are some other publicly funded early education opportunities for children in need. The federal Head Start and Early Head Start serve more than 15,000 children from Indiana’s most financially struggling families. And the state is federally required to support preschool for nearly 13,000 children ages 3-5 who have disabilities — but until this year, the funding level had remained stagnant for nearly three decades.

Without reliable state funding for pre-K, families are largely dependent on the graces of preschool programs to offer scholarships — or they foot the bill, which can cost about $9,000 per year at a high-quality provider, according to the Early Learning Advisory Committee. That’s why upper-class families hold a sizeable advantage in early education: They can afford it.

Even many public schools charge tuition for preschool, though some tap into federal funds for giving extra services to students in poverty, and some target students who might be most in need of a boost before kindergarten.

Meanwhile, other states are providing support for many more of their preschool-aged children, paying on average for one-third of them to attend pre-K, according to Steve Barnett, senior co-director and founder of the National Institute for Early Education Research. Leading states on preschool are already considering even broader expansions of early learning — to serve children earlier, at age 3, or make pre-K free and accessible to all children regardless of income.

Rural states like Indiana tend to trail in early education, Barnett said, because there has been “a sense in them that they don’t have a problem to address.”

But momentum for change is already brewing in Indiana. Some of the heaviest hitters in Indiana support pre-K — corporations like Eli Lilly and Co., nonprofits like the United Way, politicians like Holcomb and Pence.

Community movements are also rising up, such as the Strosacker Early Learning Fellows in Northwest Indiana, where local leaders work to recruit more supporters of early education.

“The stakeholders in the Region can see we’re shooting ourselves in the foot if we’re not dealing with this topic,” said Mark Chamberlain, founder and CEO of Lakeside Wealth Management in Chesterton, who was in the first class of fellows. “Just by moving the needle a little bit in the right direction, it’ll create some more awareness, and more people will jump on the train.”

Those local trailblazers will eventually force slow states like Indiana to catch up, Barnett predicted: “Because the rest of the states are going to be asking why they should be left behind.”

Seeding new opportunities in preschool deserts

After deciding not to send her preschooler to the day care that she considered “baby jail,” Alina Keller had no good options.

A relative watched her son until a new preschool opened last summer along her commute to work. A 20-minute drive away, the preschool is in a different time zone than Keller’s home in Goodland. It doesn’t rate at the top of the state’s quality scale, but for Keller, “it was really the only option.”

Still, Keller said preschool has kickstarted her son’s imagination. He’s less shy, minds his manners, and is eager to learn.

“He actually brought me the flashcards and wanted to sit down and work with them,” Keller said. “Compared to me saying, ‘Hey, if you do this, you’ll get a surprise!’ Or, ‘Hey, if you don’t do this, you’ll get in trouble.’”

Newton County, where Keller lives, is one of five counties in Indiana with no high-quality preschools. But even for many counties that have one high-quality preschool or a few, that presents limited options for parents, depending where they live.

As a result, the lack of quality preschool options creates little deserts throughout the state where people don’t have access — and often have to turn to unregulated home daycares or other programs that can be exempt from meeting even the most basic health and safety standards.

Even in more densely populated cities like Indianapolis, advocates say there aren’t enough high-quality seats. Studies have famously shown that preschool efforts fall flinchingly flat when quality isn’t taken into consideration.

The state puts about $4 million of its pre-K funds toward grants for providers to expand and improve. But that’s no easy task, especially since Indiana prioritizes having a mix of provider types. Churches in particular often struggle to meet the state’s highest standards, child care officials say, because it can be more difficult to fulfill structural and safety standards for kitchens, bathrooms, or accessibility in older buildings not intended to house preschools.

And many preschools already operate on a shoestring budget, often paying teachers dismally low salaries, in part because sometimes parents can’t afford to pay more.

On the north side of Newton County, Community Church in Roselawn is trying to fix the shortage of options, by reopening its preschool.

The church had a preschool until the local school district opened one — there wasn’t enough demand to keep both open. But the school district recently stopped offering its program, leaving the area without a licensed preschool.

“God must just have struck that desire in my heart that that was truly the thing that our community needed the most,” said Dawn Kuiper, the church’s connections coordinator.

With support from the Child Care Resource Network, and local education, economic development, and philanthropy leaders, the church secured about $150,000 through a state grant, an Early Learning Indiana grant, and private donations to renovate and restart the preschool. It plans to open a fee-based program this fall, with the goal of offering On My Way Pre-K vouchers.

“No one in our community even knows this voucher exists,” Kuiper said. “It’s like our community having food stamps, and having no grocery store you could spend them on — or not even knowing you could get them.”

MOVING 4WARD is a collaborative reporting project by IndyStar and Chalkbeat Indiana. Over the course of the next few weeks and then occasionally throughout the year, the project will examine the current state of early childhood education in Indiana with an emphasis on how best to prepare our state’s 4-year-olds (hence the project title) for kindergarten and beyond. Expect stories to take a critical look at preschool programs, issues of access to those programs, the debate over the value of taxpayer-funded universal preschool, what lessons can be learned from other states, and — perhaps most importantly — what you, as a parent, need to know to make informed decisions about choosing your child’s preschool.

Read more:

National report downgrades Indiana for excluding some families from pre-K vouchers

How much do children benefit from preschool? Ask this Indianapolis kindergarten teacher