Almost from the start, Tyris struggled at Indianapolis’ Emmerich Manual High School.

His teachers continually wrote him up for transgressions like using his phone, refusing to do work, and putting his head down on his desk. There were a few bright spots — a teacher he was close with, a gym class he liked so much he purposely flunked it to take it again. By the spring of his junior year, however, Tyris had failed so many classes that he had earned just 16 credits, a fraction of the 40 needed to graduate.

“It did break my heart,” Tyris’ mother, Candy, said after finding out in the spring that he had stopped attending regularly. “I think at that point, whatever he decided to do I was OK with.”

So Candy, who never finished high school herself, reluctantly went to the school office and filled out the paperwork she assumed would let her son drop out.

But in the eyes of Manual High School, Tyris did not drop out. According to records Candy obtained from the school at Chalkbeat’s request, Tyris was recorded as leaving Manual to be home-schooled, a designation that could help boost the school’s graduation rate.

A Chalkbeat analysis of Indiana Department of Education data found that of the roughly 3,700 Indiana high school students in the class of 2018 officially recorded as leaving to home-school, more than half were concentrated in 61 of the state’s 507 high schools — campuses where the ratio of students leaving to home-school to those earning diplomas was far above the state average. Those striking numbers suggest that Indiana’s lax regulation of home schooling and its method for calculating graduation rates are masking the extent of many schools’ dropout problems.

“There’s no accountability or follow up or monitoring” of students who leave public education to home-school, said Robert Kunzman, managing director of the International Center for Home Education Research and a professor of education at Indiana University. “That’s clearly working against children’s interests.”

When students are recorded as leaving to home-school in Indiana, they’re left out of a school’s graduation calculations, as though they never attended at all. This can improve schools’ graduation rates, which can help them earn higher letter grades on Indiana’s accountability measures and avoid intervention. At the same time, Indiana does little to ensure children and teens are genuinely educated at home. Home-schoolers don’t need to register, take state tests, or provide documentation of their education.

Put simply, there is no way to know how many Indiana students recorded as leaving high school for home schooling are getting any kind of education — and plenty of opportunity and incentive for schools to take advantage of the system.

Indiana lawmakers have taken steps this year to increase scrutiny of schools with large numbers of students leaving to home-school, but critics say a new law doesn’t go far enough. A handful of other states have faced the issue as well, though the scope of the problem is unknown, and advocates disagree about what should be done.

It’s unclear why Tyris — who asked that his last name not be used — was recorded as leaving Manual to home-school. Officials with Charter Schools USA, the for-profit operator that has run Manual since low test scores led to state takeover in 2012, would not comment on specific cases, citing privacy reasons.

The school stood out in Chalkbeat’s analysis of students leaving high school for home schooling. Manual reported that its class of 2018 numbered 83 graduates, six dropouts, and 60 students who left at some point during their high school years to be home-schooled.

“What? Yeah, there is no way,” said Rachel Coleman, executive director of the Coalition for Responsible Home Education, when presented with the data on Manual. “It sounds like the distinction between home-school and dropout is really disappearing,” she added.

Charter Schools USA officials and former school leaders stressed that no one is urged to leave, that home schooling is a parental choice, that the school lays out a range of options, and that parents often choose home schooling to avoid consequences from truancy or behavioral issues.

Colleen Reynolds, a company spokeswoman, attributed the high number of students exiting to home-school at Manual and at another low-performing Indianapolis school the company operates, Thomas Carr Howe Community High School, to the schools’ “exponentially high number of high-risk students.” Still, officials are concerned about the large numbers and introduced a new initiative this year to address them, Reynolds wrote in an emailed response to questions.

“Our ultimate goal,” she wrote, “is to have every student graduate.”

Rising grad rates — and more home-schoolers

Manual is one of the oldest high schools in Indianapolis and was once known for its vocational education. But it was hit hard by enrollment declines that rippled across Indianapolis Public Schools and lost about half its students between 2005 and 2011.

After years of low test scores, Manual was one of several campuses the state seized control of in 2012. Indiana officials brought in Florida-based Charter Schools USA, which operates 87 schools in six states, to attempt to improve Manual, Howe, and an Indianapolis middle school. The campuses are not charter schools, but the state severed them from the district and took on oversight.

Tyris enrolled at Manual four years into this experiment.

He started having problems almost immediately, according to records Candy shared with Chalkbeat that catalogued his behavior and attention issues. “Tyris refused to do his work today. He put his head down and wouldn’t respond,” wrote a teacher in the spring of his freshman year. “This behavior is becoming routine.” Yet there were glimmers of hope. A report described Tyris as polite, and his gym teacher called him a “model student.”

Tyris received special education services at Manual. He was diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder, oppositional disorder, and depressive disorder, according to a special education case conference report from 2017. Candy said Tyris also has attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

In his sophomore year, Tyris had a teacher he was especially close to, and that made school better, he recalled. He liked talking with her, and she would make sure he knew what he needed to do to pass classes, Tyris said. But she eventually left for another job.

From Candy’s perspective, Manual failed Tyris. Staff were constantly calling her over what she considered petty disagreements with him, asking her to pick him up from school, she said.

“They didn’t care enough,” Candy said.

Though Candy urged Tyris to take online credit recovery classes to catch up during his junior year, he saw little hope in continuing at Manual.

“I felt like there was no point in me going, because I wasn’t going to pass,” Tyris said.

After the school called to let her know his absences stretched into weeks, Candy decided to let her 17-year-old drop out. At least then, she reasoned, he could get a job.

When students want to leave Manual, school staff walk families through their options, then-principal Misty Ndiritu told Chalkbeat in an interview in May.

As required by the state, Ndiritu said the school informs prospective dropouts of the negative consequences of that choice, including that students who drop out earn significantly less money, are more likely to land in prison, and cannot get a driver’s license until they turn 18.

When students leave to home-school, staff tell parents they are taking on the responsibility to educate their children, Ndiritu said. Manual does not label students as leaving to home-school to boost its graduation rate, she said.

“A family has a choice to go through and sign dropout forms, to sign out to home-school, to transfer out of state, to transfer to adult ed,” Ndiritu said. “We just do our best to educate them on what options they have and listen to what issues may be causing them to leave our school and make recommendations to them.”

According to Candy, that didn’t happen the day she withdrew Tyris. She said the school receptionist gave her paperwork to sign, and she was done in minutes. Only later, Candy said, did she learn that Tyris was recorded as leaving Manual to home-school, after she sought her son’s educational records at Chalkbeat’s request.

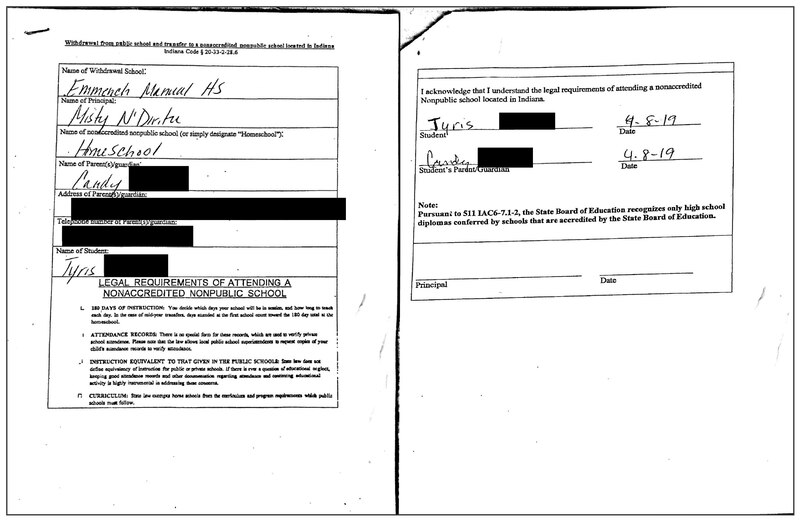

In fulfilling her records request, the school provided Candy a form saying Tyris was leaving to home-school. The front page of the form includes her name, Tyris’, and their contact information. In a box saying where he is transferring, someone wrote in “homeschool,” and the bottom of the page outlines the legal requirements for home-schooling, such as that students have 180 days of instruction. Candy said the handwriting on the form is not hers, although she said the back does bear her signature. The space for the principal’s signature is blank.

Reynolds of Charter Schools USA wrote that while she cannot discuss Tyris specifically, under the previous policy, the registrar would customarily complete the “demographics section” of withdrawal forms.

“No parent is required to sign a home school form,” Reynolds added. “If a parent signs a form, it must be legally assumed that they have read and agree with whatever is on the form.”

Candy, however, said she does not recall seeing the form before getting it with Tyris’ school records, and she did not discuss home schooling with any staff from Manual.

“There’s no way in a million years I would agree to home schooling,” said Candy, who says she has a hard time helping her children with homework. “What am I going to do to be able to help them?”

Another Manual parent and educator told Chalkbeat the school pushed the home schooling option on his family. Kevin Leineweber was a teacher at the school in 2016-17 when he said his foster son, a Manual student, briefly ran away. Leineweber said he got an email from a school official asking him to withdraw him to home-school.

“I obviously wasn’t withdrawing him for home schooling because I didn’t even know where he was,” said Leineweber, who ignored the suggestion. He also ignored another withdrawal form he received in the mail that summer, which he said was filled out and awaiting his signature.

Ndiritu, the former Manual principal, declined to discuss specific cases. She left the school this summer to take on a new role: She is now turnaround school director for Noble Education Initiative, a nonprofit with ties to Charter Schools USA that is the day-to-day operator of the company’s Indiana campuses.

In the seven years since the state took over Manual and turned management over to Charter Schools USA, some problems persist: Teachers continue to rotate in and out, and many students have discipline problems, are persistently absent, or transfer in or out mid-year, according to state data.

There have, though, been gains in that time. Most notably, the school’s state letter grade has risen from an F to a C. One factor in that grade is graduation rates, which have improved at Manual to 78% in 2018 up from 69% in 2012, the year before the school was taken over.

Manual achieved that increase while having the highest proportion of students who left to home-school, compared to graduates, out of all traditional high schools in the state, according to a Chalkbeat analysis.

If every student on the books as exiting for home schooling were counted as a dropout, Manual’s graduation rate could have plummeted to 50%. If even one-third of them were counted as dropouts, the school’s graduation rate could have dropped to 66%.

High stakes for Charter Schools USA

For many families, home schooling is a welcome and effective alternative to traditional schools.

About 1.7 million children are home-schooled in the U.S., according to a survey from the National Center for Education Statistics, a number that grew rapidly during the early 2000s. The same survey found that 15% of children who are home-schooled don’t have a parent who has completed high school. That’s a shift from a time when families who home-school were typically more educated, said Coleman of the Coalition for Responsible Home Education.

Nationally, it’s impossible to draw broad conclusions about outcomes for students who are educated at home because it is so loosely regulated and tracked.

Concerns about whether students recorded as leaving to home-school are truly getting an education, meanwhile, have arisen in a handful of other states. They include Texas, where advocates have repeatedly raised alarms that the state is undercounting students who drop out; Kentucky, where a state report last year found the number of students leaving to home-school climbed when districts raised the dropout age from 16 to 18; and Florida, where the state department of education recently reprimanded a district leader for allegedly instructing staff to inaccurately code students who withdraw as moving to home-school.

In Indiana, the number of high schoolers recorded as leaving to home-school has been declining in recent years. But at some schools, including Manual and Howe high schools, the numbers are rising.

While the number of graduates at Manual has fluctuated over the last six years under Charter Schools USA’s management, the number of students leaving to home-school has more than tripled.

The other Indianapolis high school managed by Charter Schools USA, Howe, also saw a big increase in its graduation rate, accompanied by a large number of students leaving to home-school.

The graduation rate at Howe jumped to 92% last year, the highest rate in over a decade. But if students who left to home-school are included in the calculation, the rate could have dropped 17 percentage points. The school had 56 graduates, 14 students who left to home-school, and zero dropouts in the class of 2018, according to state records.

Of the 14 students who left Howe to home-school, 13 were seniors.

In an interview this spring, then-Howe Principal Lloyd Knight said school officials never suggest students withdraw, and many families are familiar with leaving to home-school as an option from prior schools.

When parents are cited for truancy, they will often withdraw their children to home-school to avoid having to go to court, said Knight, who left Howe this summer for a job with another Indianapolis charter network.

But Knight also said there are situations where it might be appropriate for a student to leave to home-school. “If a student is struggling with behavior at a mighty rate, and there’s other interventions that have been put in place and things like that, there have been times when we say, ‘Hey, you know, home-school may be an option for you,’ ” Knight said.

Reynolds, the Charter Schools USA spokeswoman, attributes the unusually large numbers of students leaving to home-school to the population of the schools. “They unfortunately have the highest number of students who either have been transferred to us from other institutions or who believe we are the last chance,” she wrote. “Usually this decision is made based on personal situations such as pregnancy or need to work to support the family.”

But several campuses with comparable populations don’t report nearly as many students leaving to home-school as Howe and Manual. At nearby Arsenal Technical High School, 335 students graduated, 57 dropped out, and six left to home-school from the class of 2018. At Roosevelt High School, a campus in Gary that was taken over by the state at the same time as Howe and Manual, 51 students graduated, 36 dropped out, and three left to home-school.

Reynolds said Manual instituted a new policy this school year requiring parents to meet with an administrator before withdrawing their children to home-school. She said school leaders “recognized that there were some potential gaps” after meeting with state officials in light of a new law singling out schools with high numbers of students leaving to home-school.

It’s a pivotal time for both Manual and Howe. State oversight of the schools is coming to an end. And in a show of confidence in Charter Schools USA, the state board of education voted in March to instruct the company to seek charters that would allow it to continue running the campuses next year.

Although state education officials oversee the schools, state education board Chair B.J. Watts said he was not aware of how many students at Howe and Manual were leaving to home-school until Chalkbeat requested an interview for this story. He described the numbers as “alarming.”

“That’s a big number, and we want to make sure that we understand what’s happening there,” Watts said.

As the schools pursue charters, however, they could draw new scrutiny. The large number of students leaving to home-school could cast doubts on the high schools’ improvement, said former Indiana schools Superintendent Glenda Ritz, a Democrat who campaigned against state takeover in 2012.

“They’ve been showing improvement on paper,” Ritz said. “But it doesn’t give a clear picture of, perhaps, what’s going on.”

‘Our system has failed them’

The number of Indiana students, particularly high school seniors, leaving to home-school has captured state lawmakers’ attention. A bill last legislative session would have changed graduation rates to count those students as dropouts.

“Our system has failed them,” said Rep. Bob Behning, an Indianapolis Republican who chairs the House Education Committee. “Their opportunities in life are going to be significantly diminished, especially when it comes to income, by not having a high school diploma.”

Ultimately, however, lawmakers substantially weakened the bill. Home-schooling supporters don’t want families who provide a thorough education to be lumped in with those who let their children drop out of school. At the same time, traditional public school advocates are worried schools will be penalized when students leave to home-school, which could hurt the accountability grades of high schools.

Lawmakers instead approved a much narrower plan that requires high schools with large numbers of students leaving to home-school to demonstrate “good cause” to the state board before removing them from the graduation calculations. High schools with more than 100 students in the graduating class will face extra scrutiny if more than 5% leave to home-school and those students are not on track to earn diplomas. For schools with 100 or fewer students in the graduating class, the threshold is 10%.

State officials are still working out how they will determine “good cause” and enforce the new law. But they say their intervention in schools is unlikely to include the kind of in-person interviews with students and parents that would reveal the experience behind the paperwork.

“At the end of the day, we are not going to interfere between a conversation or communication between a school guidance counselor and a parent or family,” said Ron Sandlin, senior director of school performance and transformation for the state board of education.

Instead, lawmakers and officials say they hope shining a light on the issue will be enough to deter any potential abuse and push communities to pay attention to how many students are leaving their high schools without diplomas.

Indiana’s legislation may be a politically palatable way to mitigate the problem, said Robert Balfanz, director of the Everyone Graduates Center at Johns Hopkins University, which conducts research and provides support for increasing graduation rates. But he believes focusing on whether schools fulfill paperwork requirements is not good enough.

“The state needs to really be invested in getting accurate measures of how many people are actually earning diplomas,” Balfanz said. “If our public education system is not graduating our kids positioned to support families, that undermines whole communities.”

For Tyris, the future remains uncertain. When he turns 18 this fall, he plans to get a job in landscaping or working in a warehouse. And recently, he started talking about enrolling in virtual school, which gave his mom a little burst of hope and pride. But he’s still far from graduating.

Charter Schools USA officials say school staff follow up with Manual students who leave to home-school to encourage them to finish school, whether at Manual or an alternative program.

Candy said she heard from the school several times during the summer break, but they weren’t checking in on Tyris.

They were calling to recruit her younger son, who was entering ninth grade.