As a handful of teaching majors at Marian University prepared to lead a class for the first time, they nervously flipped through their notes. A few prepared a script for how to introduce themselves and establish ground rules.

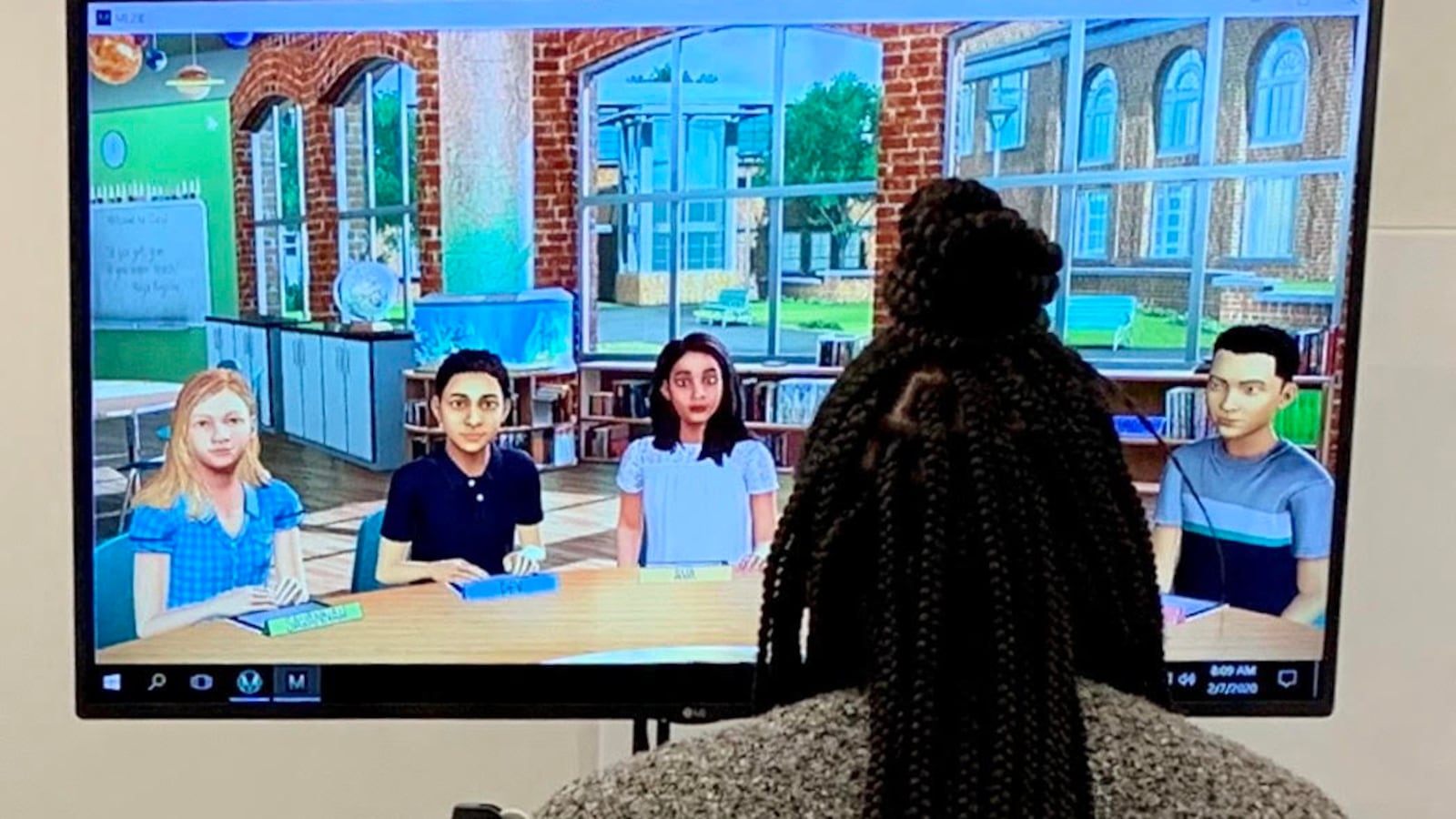

One by one they stood up and began teaching. But instead of a room full of kids, they each faced a large monitor with five “digital students” looking back at them. It’s a simulation, and the avatars can “see” the student teacher through the camera and respond in real-time, each with a unique personality.

The Marian students are getting an early start on learning how to run a classroom, rather than waiting until their junior or senior year to student teach real-life children. The university’s new and unusual approach is part of a retooled program for training teachers, one that focuses on constant practice and immediate feedback.

The mixed-reality program is run using both computer programming and a simulation specialist, who is watching and can turn up or dial back the avatars’ classroom behavior. Think, the man behind the curtain in “The Wizard of Oz.”

To demonstrate what it’s like to teach virtual students, Professor Karen Betz introduced herself, established her classroom rules, then asked each student for a fun fact. She offered her own, too: that she’d been struck by lightning twice, once in an airplane. Then she began calling on the avatars.

“Well, it’s not as cool as being struck by lightning…” an avatar named “Dev” began in a tinny voice.

The Marian students’ faces lit up with surprise at the specific response. To make it more effective, students aren’t told exactly how this program works. Freshman Lindsey Meyer chalked it up to “magic.” Betz instructs them to think of the avatars as real students.

On Friday, the freshmen practiced pausing appropriately, positively reinforcing what their students said, and getting the group’s attention back after a few seconds of talking amongst themselves. Meanwhile, they were reviewed by both Betz and a classmate.

Each had a minute and a half to introduce themselves and begin getting to know their students. Then Betz paused the simulation and reviewed what went well and what needed work before giving them another minute of practice.

Marian University brought in the simulation, developed by Mursion, two years ago. Inspiration for the approach came from the university’s medical school, where students practice treatments on computerized mannequins. Kenith Britt, dean of the Klipsch Educators College, said school leaders began brainstorming what that kind of training environment would look like for teachers.

“That’s one of the challenges with education prep today,” Britt said. “There’s not a lot of immediate feedback going on. And if there is, it’s infrequent and they cover too much stuff.”

Marian students use the program throughout their teaching courses. As they build on their skills, the student teachers could deal with a virtual student looking at their phone, putting down a classmate, or having an outburst related to autism. Eventually, they will practice running a parent-teacher conference.

“I like that I’m thrown in because it gives me a feel of if I want it or not,” said Treanna McKinney, a Marian freshman, who says she loved interacting with the virtual students. McKinney said she was scared for her first simulation, but that it went better than expected.

She asked the students about their favorite foods, but there was an awkward pause when she didn’t call on one of them to get their responses started. That’s something to work on, Betz said.

The idea is to practice de-escalating conflict and avoiding triggers now, so would-be teachers are confident when they walk into a room of real students.

“Our next big push needs to be education because we haven’t been able to solve the issue of underperformance for decades, especially in urban schools,” Britt said. “At the end of the day, that’s all we are trying to do — make sure that when teachers go into the field, that the first day they step foot in a classroom, they are going to improve their kids.”