For the first time in seven years, Indianapolis Public Schools is buying new English materials for dozens of schools across the district.

The school board in the state’s largest district approved a plan Thursday to spend up to $4 million to adopt new English curriculums, which include textbooks.

Districts typically replace books every six years, but amid years of budget freezes, it has been more than a decade since the district purchased new English textbooks for middle and high schools. At elementary schools, it’s been seven years.

The current textbooks and other materials schools are using are “pretty patchwork,” said Superintendent Aleesia Johnson. That puts additional pressure on teachers to fill in the gaps.

“I want [teachers] spending time planning and thinking about the lesson and how to make it fit for the students they are serving,” Johnson added. “I don’t want them spending hours on the internet trying to find materials to use in class.”

The new curriculums have been vetted by district officials, Johnson said, to ensure materials reflect student diversity, are high quality, and align with state standards, last overhauled in 2014, for what students should be learning.

Read: Overdue for a change: IPS is poised to roll out new English curriculums

Along with new textbooks, the district will also increase fees by about $50 per student. Indiana is one of a handful of states that allow material rental fees, a controversial practice that shifts the cost of school supplies to families. Total per-student fees vary widely by school. Because many of its books are older, an Indianapolis Star report found that Indianapolis Public Schools has low fees compared to many of its neighboring districts. The IPS board also approved a contract Thursday with a collections agency that will attempt to recoup some unpaid textbook fees through letters and calls to parents.

All of the neighborhood schools will use the new English materials. But some campuses will not use the new books, including many magnets with special focuses, such as the district’s three Montessori schools, and innovation schools — considered part of the district but independently managed. (Innovation schools are responsible for choosing and purchasing their own curriculums.)

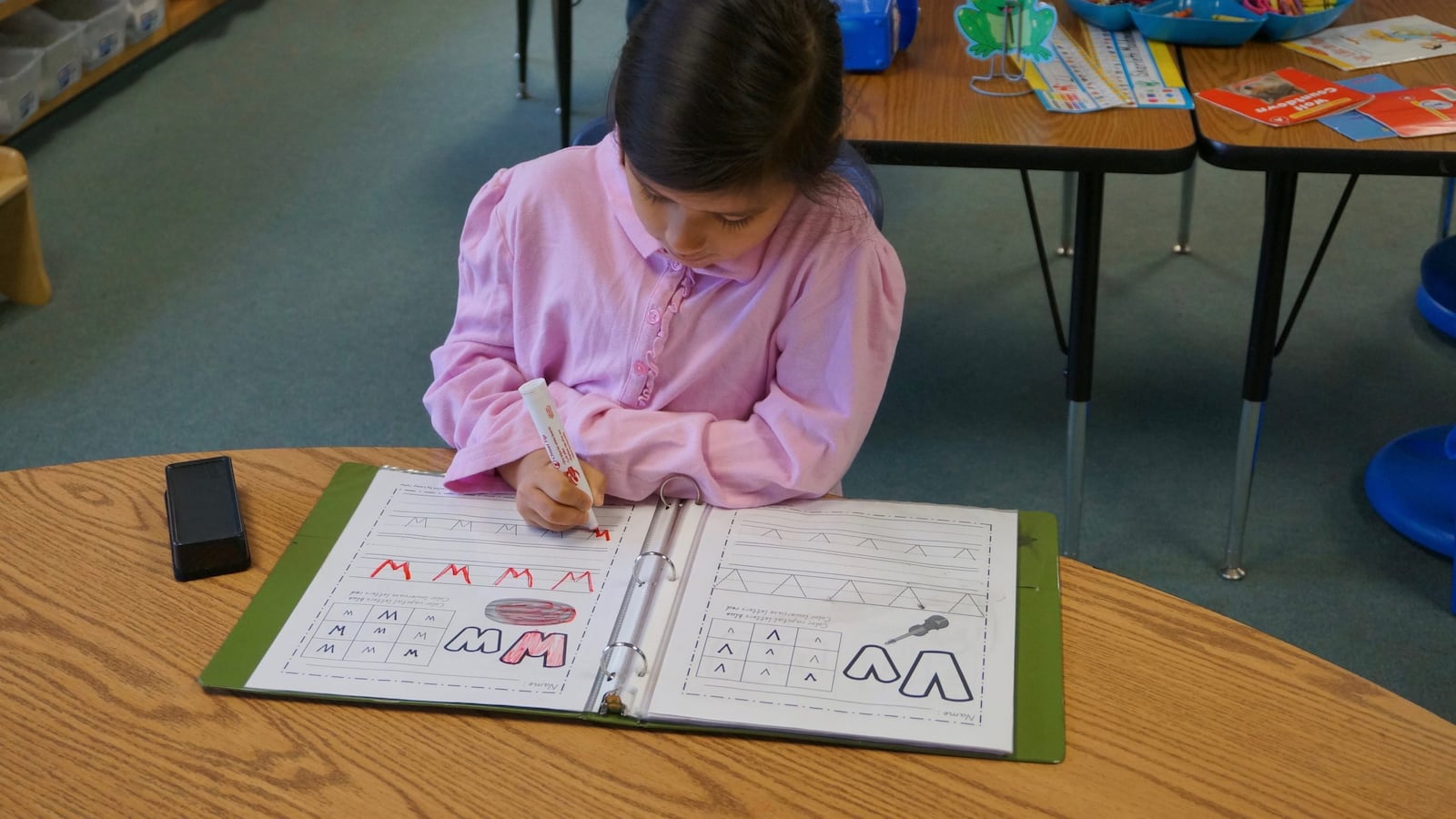

The district chose a single curriculum for elementary grades and two options for middle schools. At elementary schools, the district will use Into Reading by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, a newly released curriculum that includes many lessons and supplementary materials. At middle school, schools will either use Into Reading or Wit & Wisdom from GreatMinds, which emphasizes high-quality texts.

Most of the district’s high schools will use myPerspectives from Pearson and materials from Bedford Freeman & Worth for honors and Advanced Placement courses. Shortridge High School will use textbooks from Hodder Education for International Baccalaureate courses, another advanced program.

District officials chose curriculums in part because a large portion of the texts focus on science and social studies, said Jessica Dunn, the interim curriculum officer for the district.

The district will also run teacher training in the summer and fall to encourage educators to integrate the new curriculums so they “are not sitting on shelves collecting dust,” Dunn said. “We want these materials to be used.”

The decision to adopt a single curriculum for most elementary schools is a shift for the district, which has emphasized the importance of giving principals more independence in recent years. When Indianapolis Public Schools purchased math curriculum three years ago, it adopted several programs so schools had options.

But Johnson sees advantages to using the same English curriculum at most schools. It will make it easier for students who transfer between district schools mid-year, and it will improve support for schools because central office staff will know the materials well, she said.

“We don’t ever want autonomy to be for the sake of autonomy,” Johnson said. “Having autonomy is so that we can move the needle on student outcomes.”