Matthew Perkins had ambitious plans for his eighth-grade science students: This spring, they were going to take a walk to observe nature like Charles Darwin did, use M&Ms to understand genetics, and dissect fetal pigs.

Those plans are on hold, however, after Indiana shuttered campuses for at least six weeks — and potentially the remainder of the academic year — in an effort to reduce the spread of the new coronavirus. Now districts, principals, and teachers are trying to pick up the pieces and adapt to remote learning as the nation struggles amid the current pandemic. But when learning goes remote, students suffer big losses — even at the most prepared schools.

Children won’t be able to do hands-on science projects in labs or use manipulatives to learn math, such as rulers and shapes districts purchased for this purpose. Teachers will struggle to monitor from afar how students are doing. And students will lose out on the benefit of working with and learning from their peers in real-time and in person.

If students are not able to return to school this academic year, teachers will need to “pick up the slack and do a lot of remediation,” said Perkins, an Indianapolis educator who teaches at Westlane Middle School in Washington Township. Otherwise, students who were already struggling “are going to continue to get further and further behind.”

Indiana Gov. Eric Holcomb has mandated that schools remain closed at least through May 1, and he said it would be a “miracle” if they reopen this academic year. Schools are not required to offer instruction during those closures. Nonetheless, many districts across the state are attempting to teach remotely or plan to do so once students return from spring break.

Indiana educators largely consider remote education to be a stop-gap measure. It’s not as effective as going to school and interacting with teachers and students in person, they say. But it’s their best tool to keep students learning during extended campus closures.

“Right now, we are just triaging,” said Michael Barbour, associate professor of instructional design for the College of Education and Health Science at Touro University in California.

“The reality is that there’s a certain percentage of the content that’s not going to get covered this year. And that’s the reality for every K-12 student that’s out there right now.”

In some schools, remote learning is done online, and students can connect with teachers and peers through video. At schools where many students don’t have access to devices or the internet, educators are instead relying on paper handouts to fill the gap.

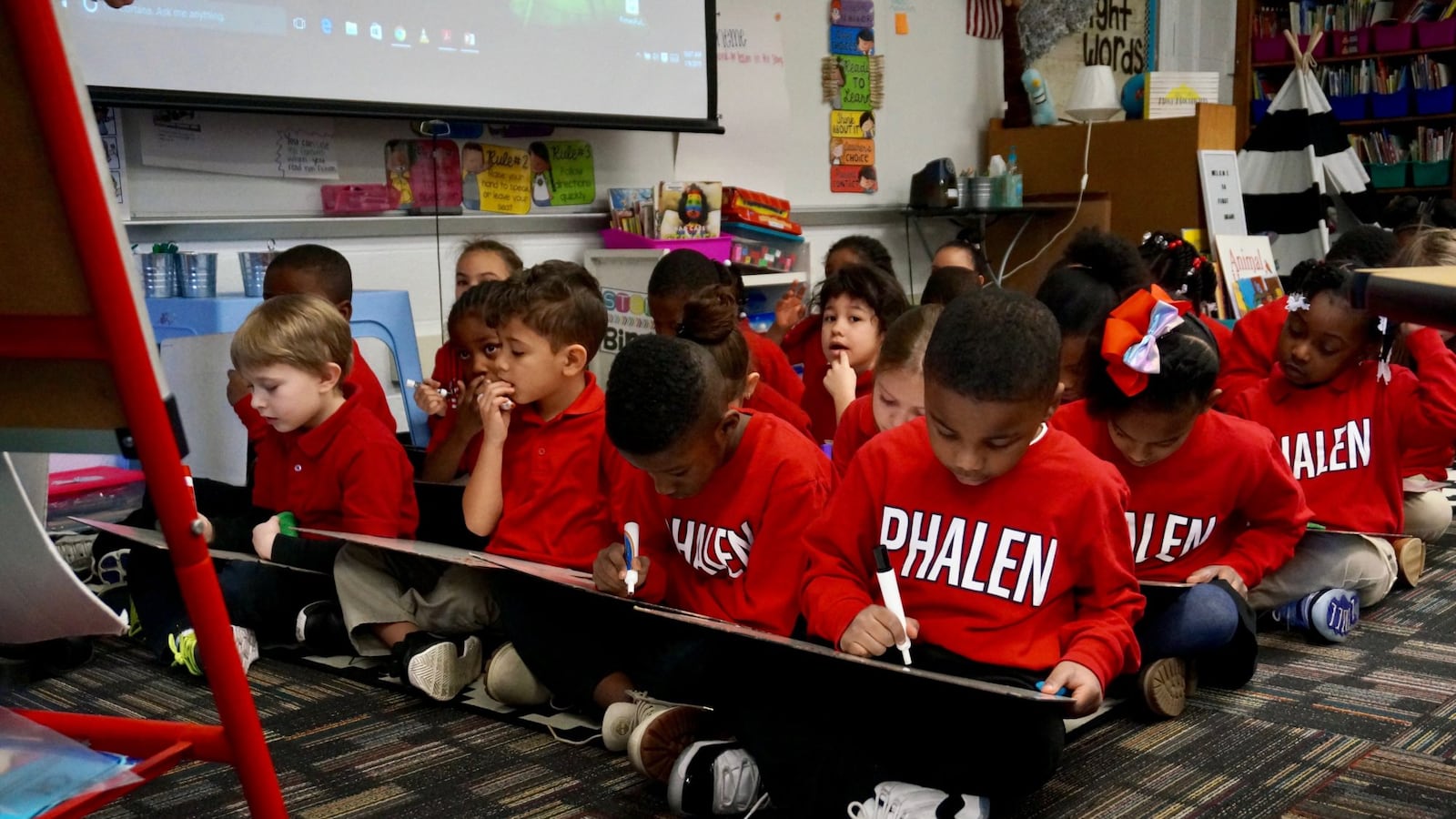

At Phalen Leadership Academies, which runs four schools in Indianapolis, many students do not have tablets or laptops at home and the schools do not have enough devices to give to children, said Nicole Fama, principal of the charter network’s Indianapolis middle and high school.

So Phalen gave students large packets of schoolwork. Before the closures, their middle schoolers, for example, took home over 150 pages of work. Without being able to video chat with teachers and classmates, however, Fama worries about the academic and social implications.

As the federal government debates a $2.2 trillion bill to combat the economic impact of the coronavirus, Fama said, “I am waiting for the bailout for education that includes giving all the kids technology.”

Juanita Price, who teaches second grade at School 94 in Indianapolis Public Schools, also believes that getting families access to technology is essential for remote learning. When young children struggle with schoolwork, they can’t always articulate that they are having a problem or what it is, she said. As a teacher, she relies on walking around, watching students work to see when they are struggling.

If she can video chat with students, she hopes it will replicate some of that interaction. “I believe that if I can see them, that I’ll still be able to help,” Price said.

Typically during the first week of Avondale Meadows Academy’s two-week spring break, Courtney Spurgeon would be holding remediation classes for struggling students. Instead, she’s video conferencing with other teachers from the K-5 Indianapolis charter school, trying to figure out how to help students remotely when the break ends.

Before schools closed, Spurgeon, an intervention specialist for math, was helping her students — including many who have disabilities — work through fractions and measurements. Her students benefit from being able to physically manipulate a ruler or blocks to help them grasp the concepts.

Sending them a video won’t be the same, she said.

“We’re all really scared,” Spurgeon said. “Every kid is going to come in significantly behind.”

Over the next several weeks, teachers will grapple with how to change their approach to keep students doing school work — even if it’s on a laptop or in a paper packet. The latest experiment for Perkins, the science teacher from Indianapolis, is making TikTok dance videos about genetics for his students.

“I’m getting a lot of students responding, ‘This is ridiculous. Why would you do that to yourself?’ But at least I know [that] they are checking in,” Perkins said.