For months, a racially charged debate has been raging behind the scenes at Science Park High School about how one of Newark’s most elite schools selects its students.

Last week, it erupted into full view.

Science Park is the district’s most popular public high school, a selective magnet school that was the top choice for students applying to high school last year. But the National Blue Ribbon School’s enrollment does not reflect the district’s: A disproportionately small share of its students are black and a disproportionately large share are white, while relatively few hail from certain city wards with many black residents — including the Central Ward, where it’s located.

In response, a group of mostly black parents has been urging the administration to overhaul its admission system, which is based primarily on students’ state test scores. The parents have suggested interviewing applicants, focusing on their report cards, and potentially reserving seats for students from each ward.

The administration has made some minor changes to its admissions policies, but not enough to satisfy the parent group — which was evident last Thursday when the Science Park administration hosted a public town-hall meeting to discuss those policies.

The group, known as the Blue Ribbon Parents, boycotted the administration’s meeting until the final minutes, when the father of a Science Park student entered the auditorium and asked how the district could “legally and in good conscience” allow the current admissions system. The school’s principal, Kathleen Tierney, left before the man finished speaking.

“That was so disrespectful,” said Juwana Montgomery, whose twin sons are in ninth-grade at Science Park, after the meeting’s abrupt end. “They’re not addressing anything. Everything is a pushback, a pushback, a pushback, a pushback.”

The debate at Science Park mirrors longstanding ones at prestigious universities across the country and at elite public high schools in cities such as Boston, Chicago, and New York. The question is whether highly selective schools can find ways to be both exclusive and diverse, bastions for top achievers that are equally accessible to students from all backgrounds.

In Newark, the debate centers around the city’s magnet schools, which are allowed by the district to screen students based on their test scores, grades, attendance records, and, in some cases, upon the results of interviews or auditions. They are the district’s most popular high schools and its highest performing. But there are also large racial and ethnic disparities among the district’s six magnet schools and between some of them and the district’s eight traditional high schools, according to a school board report released in June.

“We were able to make it plain with the data that our schools are highly segregated,” said board member Leah Owens.

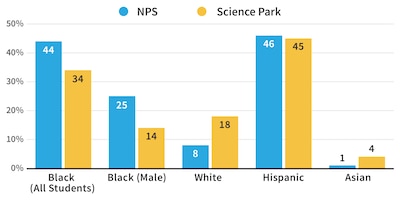

At Science Park, some parents and students say the school’s enrollment imbalances have contributed to racial tensions. Some black students in particular — who make up 34 percent of Science Park’s enrollment compared to 44 percent across the district — say they sometimes feel unwelcome at the school.

Several parents and students said they had witnessed or heard about white and Hispanic students using the N-word, occasionally directed at black students. District officials called the allegations “alarming” and said they were investigating them, while also bringing in an expert from Rutgers University-Newark to assess the “tenor” of the school. On Wednesday, Science Park is planning to gather its students for a forum on cultural sensitivity.

For students like Azé Williams, a 10th-grader, it’s impossible to separate the school’s racial tensions from its admissions policies, which have left black students and those from certain wards underrepresented. Not only that, but some teachers have opposed policy changes designed to bring in more black students, Williams said, on the grounds that doing so would lower the school’s standards.

“We don’t feel comfortable,” Williams said. “Black students, in particular, feel outcast — we feel like we are not protected.”

At Science Park, 18 percent of students are white — compared to 8 percent across the district. And just 14 percent are black males, compared to 25 percent across the district. The school’s 45 percent share of Hispanic students is about even with the district, while its 4 percent share of Asian students is larger than the district’s.

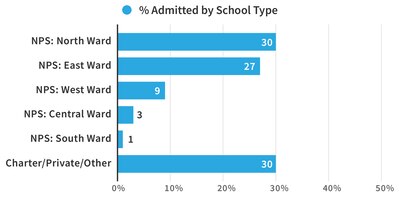

Meanwhile, nearly 60 percent of Science Park students come from district-run schools in the city’s north and east wards — which have large Hispanic populations — while only 13 percent went to district schools in the city’s south, central and west wards, where most black residents are concentrated, according to district data. Another 30 percent of students previously attended charter or private schools.

The Blue Ribbon Parent group blames those enrollment disparities on Science Park’s admissions criteria. Until this year, the school based 80 percent of applicants’ ranking on their PARCC test scores, 15 percent on their grades, and 5 percent on their attendance records. The parents say this system is inherently biased against black students, who on average have lower PARCC scores than their white and Hispanic peers in Newark and across the state.

As an alternative, the parents proposed flipping the criteria so that students’ grades counted for 80 percent of their ranking, 15 percent was based on attendance, and 5 percent based on PARCC. Other recommendations included admitting the top students from each city school — an approach used by some universities to promote diversity — or reserving 20 percent of seats for students from each of the five wards.

Still other parents wanted to bring back student interviews and personal essays, which were part of the school’s screening process several years ago. And they said the school needs to do a better job recruiting underrepresented students.

“I told them quite clearly: We need more African Americans in that school — and we have to do it now, immediately,” said Kevin Maynor, whose son graduated from Science Park and whose daughter is in 10th-grade there. Presently, the school’s population “doesn’t reflect the brilliance that’s here in the city.”

After months of negotiations, Science Park’s administration agreed to tweak the admissions criteria that it used this year to select new students for 2018-19.

Now, PARCC scores count for 70 percent of students’ rankings and transcripts are worth 25 percent, while attendance is still 5 percent. The school also redacted students’ names, genders, and sending schools from their applications before ranking them, which parents had recommended. But the parents said those changes were insufficient.

At the town-hall meeting, Principal Tierney summarized the Blue Ribbon Parents’ demands and the admissions changes she made, but she did not respond to questions from the public. Instead, attendees were divided up and ushered into separate rooms to hold small-group discussions — a format that parents interpreted as a way to stifle public debate.

Tierney did not respond to an interview request. But in her opening remarks at the meeting, she suggested that she is open to further changes to the school’s admissions system.

“We need to talk about ways in which the admissions process can promote the diversity of the student body in a legal and equitable fashion,” she said.

District officials also appear open to additional changes. At a school meeting in January, officials suggested that Science Park could do targeted outreach to students in underrepresented neighborhoods and schools, give preferences to underrepresented groups in its admissions formula, and add more screening criteria, according to slides from their presentation.

During brief remarks at the start of last week’s town-hall meeting, Interim Superintendent Robert Gregory made clear that he thinks Science Park’s current admissions system needs to be reexamined.

“The question raised that brought us here tonight is an important one and the right one,” he told the audience. “Does the use of standardized assessments unfairly limit students’ access into one of our highest-performing high schools because of their birth circumstances or the part of the city that they live in?”

But even Science Park faculty members who support the parents’ push for a more representative enrollment have some concerns about their proposals.

Nicole Sanderson, a Science Park history teacher, said she thinks the parents are right that the current admissions system excludes some students. She and her colleagues “would love to see more black boys at the school,” she said.

However, she worries that taking a certain share of students from every ward or basing admissions primarily on report cards could “backfire,” leaving some admitted students under-prepared for the rigor of Science Park classes. She suggested creating a Science Park-specific entrance exam and offering tutoring to students at feeder schools to help prepare them.

“There’s just no easy fix,” she said. “This has to be a multiyear and a multistep process.”