For the first time in over two decades, the Newark school board — rather than the state — will soon choose the district’s next superintendent. But first, the finalists for the job will get to make their case to the public.

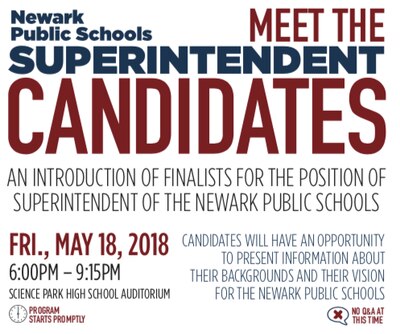

The finalists will “present information about their backgrounds and their vision” for New Jersey’s largest school district at a public forum on May 18, according to a recently posted notice for the event. Members of the public will not be allowed to ask questions during the three-hour event, according to the notice.

The finalists were chosen by a search committee last month, but the board has yet to announce their names. Newark’s Interim Superintendent Robert Gregory is the only candidate to say publicly that he has applied for the position, but Roger Leon, an assistant superintendent in Newark, and Andres Alonso, a Harvard education professor and former Baltimore schools chief, are also said to be in the running. There may be at least one additional candidate as well.

The forum appears to be a compromise of sorts between those who want the board to follow standard protocol for superintendent searches nationally (in which the names of candidates typically remain confidential) and some Newark residents who are demanding a level of transparency and input they felt were absent during the years of state control.

“They cannot forget the voice of the people — the people who are impacted by this,” said Wilhelmina Holder, a longtime Newark education activist. “There’s nothing greater than having the correct leader leading the schools, sharing the community’s vision on what’s important.”

Newark’s board regained control of the schools in February, allowing it to choose the superintendent for the first time since the state took over the district in 1995. However, its search process is largely determined by a state plan designed to guide the district back to local control.

That plan dictates that the search be led by a seven-person committee made up of three school board members elected by the public but who represent a minority on the committee, plus a state representative appointed by the state education commissioner, and three people with a “longstanding connection to Newark,” jointly chosen by Mayor Ras Baraka and the commissioner.

The board members are Kim Gaddy, Leah Owens, and Josephine Garcia, the new board chair. The Newark representatives are former superintendent Marion Bolden, Rutgers University-Newark Chancellor Nancy Cantor, and Irene Cooper-Basch, executive officer of the Victoria Foundation.

The plan also says that the broader public should weigh in on the “ideal candidate profile,” and that a private firm should conduct a national search for candidates.

The district hired the firm Hazard, Young, Attea & Associates, which asked Newark parents, students, educators, and community members what qualities they wanted in their next superintendent. The firm summarized its findings in a public report, which was based on over 1,200 survey responses and meetings that included 400 people.

The firm also presented superintendent candidates from a national pool to the search committee, which interviewed them and came up with a shortlist. The last step is for the board to make an offer to one of these finalists by May 31.

Whether the board would reveal the identities of these remaining contenders has been the subject of some speculation. The state-created plan calls only for the candidates’ names to remain confidential until the finalists are chosen, leaving it up to the board to decide whether to share its shortlist with the public.

Some school boards worry that public superintendent searches will deter candidates who don’t want the districts where they are currently working to know they’ve put their hat in the ring elsewhere. As a result, school boards typically keep candidates’ identities a secret, said Frank Belluscio, deputy executive director of the New Jersey School Boards Association.

“In the search process, there is an expectation of confidentiality on the part of the applicant,” he said in an email. “Therefore, in almost all cases, the names of the final candidates are not released publicly.”

Belluscio added that boards could face legal action if they reveal applicants’ names without their permission. However, if the candidates agree to it, boards can host public forums like the one Newark is planning. In nearby Montclair, the school board hosted a public candidate interview in February.

Chris Gaines, a district leader in Missouri who is president-elect of AASA, a national school-superintendents association, said many of his colleagues will not apply to districts with public searches. He said the community should be asked what it wants in a superintendent, but the school board should remain solely responsible for hiring decisions.

“If the superintendent is going to be accountable to that body,” he said, “I tend to think that body is the one that should make the selection.”

Not everyone agrees. Terre Davis, a former superintendent who helps school boards with their searches, wrote an article for the AASA, arguing that boards should announce the finalists and hold public interviews.

Open searches create buy-in from the public — which was sometimes lacking during the years that Newark’s schools were under state control — and allow candidates to make sure the district is a good fit before committing, she wrote. By contrast, secretive searches can lead to “harmful gossip and misinformation” about how the board made its selection.

“Searches conducted behind closed doors promote the new superintendent as the board’s superintendent,” Davis wrote, “not the community’s superintendent.”

Newark’s board will move its search into the open on May 18, when the finalist forum is scheduled for 6 to 9:15 p.m. at Science Park High School.