More Newark students are enrolling in college and earning degrees, according to a new analysis that tracks the trajectories of thousands of students after high school.

Yet even with those gains, most Newark students still end up with only a high school diploma, putting them on par with low-income students across the country but behind the rest of the state and the U.S. overall in terms of college attainment.

Whether Newark students complete college depends to a large extent on which high school they attend, according to the report by the Newark City of Learning Collaborative and Rutgers University-Newark’s School of Public Affairs and Administration. Graduates of the city’s selective magnet schools are three times as likely to earn a college degree within six years as traditional high schools graduates are.

The findings are likely to stoke continued debate about the disparities between Newark’s magnet schools, which admit mostly higher-achieving students, and the city’s traditional “comprehensive” high schools, which enroll far more students with disabilities and those with lower test scores. And as this year’s high school graduation rate is expected to top 78 percent, potentially setting a new record, the report raises the question of how to guide more of those graduates to and through college.

“There’s good news here: More Newark students are going to college,” said Reginald Lewis, executive director of the Newark City of Learning Collaborative, a public-private partnership focused on increasing college attainment in Newark. Just 19 percent of city residents have a college degree, compared to 45 percent of New Jersey residents and 40 percent of Americans nationwide.

“However,” Lewis added, “we also know from this work that we need to do a much better job assisting our young people as they move towards college completion.”

The report, by researchers Kristi Donaldson and Jeffrey R. Backstrand, tracked some 13,500 students who graduated high school from 2011 to 2016, or about 85 percent of all Newark graduates during that period. Most attended district-run public schools, but the report also included data from vocational and technical, or “vo-tech,” high schools run by Essex County; Newark Collegiate Academy, a charter school operated by KIPP New Jersey; and St. Benedict’s Preparatory School, an all-male Catholic school. (The charter schools Marion P. Thomas, North Star Academy, and People’s Prep declined to participate, as did the parochial schools Christ the King Preparatory, Seton Hall Preparatory, and St. Vincent Academy.)

Building off a 2014 report that looked at older data, the researchers set out to determine how many Newark students are going to college, staying enrolled, and graduating. They found some encouraging trends, but also stark disparities among graduates of different schools.

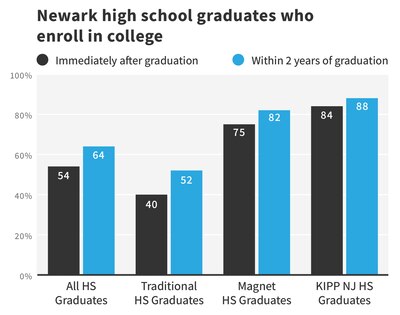

On average, they found that 51 percent of Newark Public School students who graduated high school between 2011 and 2016 immediately enrolled in college, compared to 39 percent of graduates from 2004 to 2010 who did so.

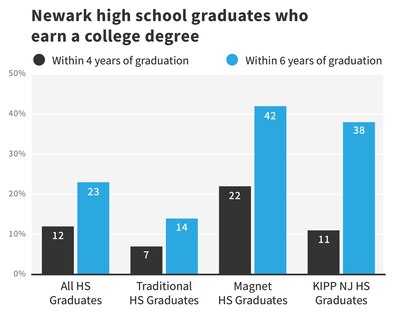

Six years after high school, 23 percent of the class of 2011 had earned a college degree or certificate — more than double the rate of the class of 2006. (Nationally, the six-year college completion rate for the class of 2011 was 57 percent. But among high schools where most students qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, the rate was closer to 19 percent, according to an analysis of the class of 2010.)

Students who begin college right after high school are more likely to graduate, according to research on “academic momentum.” From 2011 to 2015, the percentage of so-called immediate enrollers across all school types in the study grew from about 52 to 56 percent, before dipping to 53.5 percent in 2016.

However, those rates vary sharply by sector. Three-fourths of graduates from the city’s six magnet schools, which screen applicants based on their academic records or artistic talent, immediately began college, as did 84 percent of KIPP graduates, 73 percent of St. Benedict’s graduates, and 63 percent of vo-tech graduates. Among the city’s eight traditional high schools, the rate was 40 percent.

Across school types, a growing number of students are heading to four-year colleges. Still, fewer than 10 percent make it to “highly competitive” or “very competitive” institutions, such as Rutgers University-New Brunswick or New Jersey Institute of Technology, which tend to have higher graduation rates than less competitive schools. Instead, the most common destination is Essex County College, a public two-year college based in Newark.

Enrolling in college is also no guarantee of eventually earning a diploma. Among the class of 2011, 42 percent of magnet school graduates earned a college degree or certificate within six years, as did 41 percent of St. Benedict’s graduates and 23 percent of vo-tech graduates. Only 14 percent of comprehensive school graduates made it across the finish line.

“While these numbers represent improvement over previous years, they remain far from where we should be,” Newark Public Schools Superintendent Roger León said in a statement. “Our goal in Newark and my commitment is to propel students in an upward trajectory.”

The report does not delve into what causes so many students to fall short of a degree. But a majority of Newark students qualify as “economically disadvantaged,” according to state data, meaning they are eligible for free or reduced-price lunch. Research has shown that poor students are far less likely than their wealthy peers to earn college degrees — even poor students with top test scores are only as likely to finish college as affluent students with middling scores.

Academics are a major hurdle. Low-income students are more likely to attend high schools that do not prepare them for college-level work and to attend colleges that offer less academic support and have lower graduation rates, according to researchers.

In the 2016-17 school year, just 6 percent of Newark students earned what are generally considered passing scores on at least one Advanced Placement or International Baccalaureate exam, which cover college-level material. Statewide, 24 percent of students passed one or more of those exams, according to state data.

“Rigor is the problem,” said Wilhelmina Holder, president of Newark’s Secondary Parent Council, noting that many Newark students do not take college-level classes in high school. Holder, who leads a workshop at Rutgers-Newark on surviving the first year of college, said she meets students who have never seen a course syllabus or written a research paper and who struggle with reading comprehension.

Social and financial challenges trip up other students. Kei-Sygh Thomas, who graduated from KIPP’s Newark Collegiate Academy, where most students are black, had few non-Hispanic white classmates before starting at Drew University, a small liberal arts school west of Newark where about half of students are white. She was also the first in her immediate family to attend college.

“It was just culture shock in every sense of the word,” she said.

At the same time, she was under severe financial strain. She often had to split the paycheck from her campus work-study job with her family to help them afford rent and bill payments. Eventually, she dropped out.

“It just seemed like I needed money more than a degree at that moment,” she said.

Using private funds unavailable to most traditional schools, KIPP employs a team of counselors to buttress its graduates in college and offers some book stipends and emergency financial aid. Still, even with these supports, only 38 percent of KIPP graduates earn a college degree within six years of high school.

“We’re proud of the hard work of our alumni and our KIPP Through College team,” said Ben Cope, KIPP New Jersey’s chief external officer, “but we think there’s still a long way to go before we have truly closed the opportunity gap.”

This fall, the research team will present their findings to the public in a series of community meetings in each ward.

Around that time, Kevin Bernard, who graduated from East Side High School in June, will be starting classes at Montclair State University. He credits his counselor and teachers with helping him successfully apply for financial aid, and his older sisters with taking him on college visits.

Still, he worries how he and his parents, Haitian immigrants who did not attend college, will afford the tuition. A poet and activist, he is determined to join the small share of graduates from Newark’s traditional high schools who finish college.

“College is another step for me to reach my goals,” he said, “so society can look at me as an individual who’s trying to change the world.”