Newark’s new superintendent is eliminating a program that extended the hours of struggling schools, which the teachers union has long attacked as ineffective and unfair to educators.

Teachers at roughly 30 schools will no longer receive $3,000 annual stipends for the extra hours, a provision written into the current teachers contract, which extends to 2019. Instead, all 64 district schools will get extra funding for before and after-school programs, Superintendent Roger León said in an email to employees on Tuesday.

The changes will go into effect Monday, Sept. 10, resulting in new hours for the affected schools just days after the new school year began. The district is still working to adjust pickup times for students who are bused to school, according to León’s email. A few of the schools will phase out their extended hours later in the year, the email said.

“We will not continue to do the same things as before and be surprised when the results do not change,” León wrote, adding that cutting the extra hours would save the district $5 million.

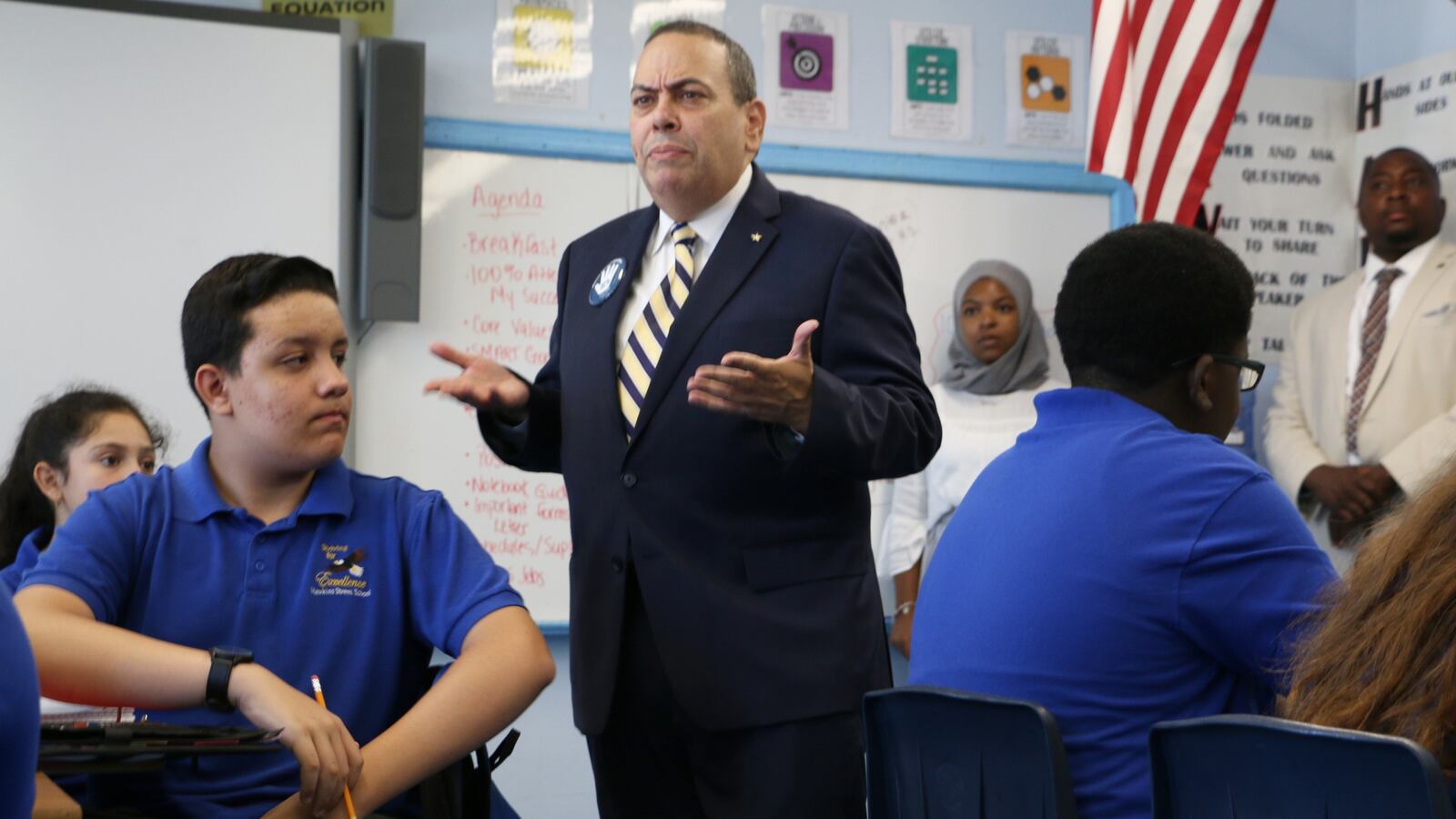

In an interview with Chalkbeat Thursday, León said the move is intended to create more uniformity among schools and the services they provide. Now, all schools will get additional money to pay for programs outside of the regular school day, which schools can tailor to their individual needs, though students who are struggling academically will continue to receive “intensive” support, he said.

“Ultimately, the idea would be by October having completely different after-school and before-school programming that meets the needs of each respective school,” León said.

The extended time was first included in the teachers contract in 2012 as part of a larger improvement plan for the targeted schools, which was developed by Cami Anderson, Newark’s former state-appointed superintendent. The plan also designated some low-performing schools as “renew” schools, where teachers had to reapply for their positions and work longer hours.

Anderson also closed some schools and gave principals new hiring authority. Both actions left dozens of tenured teachers without positions, so Anderson created a fund to pay those teachers to perform support duties in schools. In 2014, that fund for “employees without placement” cost the district $35 million out of its nearly $1 billion budget, though by last year the fund had shrunk to $8 million for about 100 unassigned teachers, according to officials.

León said in Tuesday’s email that he was also eliminating the fund, which he said would save the district another $6 million. The teachers union president said he believed all the unassigned teachers now have placements, but the district did not respond to a request to confirm that.

León is also removing the “renew” and “turnaround” labels from low-performing schools, citing their “progress and student achievement,” according to the email.

“I applaud everyone’s efforts at renew or turnaround schools and acknowledge what has been accomplished,” he wrote.

Now that León has abolished his predecessors’ school-improvement program, he will be expected to create his own. Many schools remain mired in poor performance, even as the district overall has made strides in recent years.

When the teachers union agreed to the extended hours in its 2012 contract with the district, it was hailed nationally as a major breakthrough in efforts to revamp troubled schools. But even as the union agreed last year to keep the provision in its current contract, union officials have assailed the turnaround effort as a failure.

NTU President John Abeigon told Chalkbeat on Thursday that the program had been a “scam” and “nothing more than extended childcare.” He added that the stipend teachers received amounted to about $7 per hour for the extra time they worked.

In 2016, a district-commissioned survey of 787 teachers at schools with extended hours found that two-thirds of teachers at schools where the extra time was spent on student instruction said the time was valuable. But in a survey the union conducted in April, the 278 teachers who responded gave the extended hours low ratings for effectiveness in boosting student achievement.

Some teachers in the union survey praised the longer hours, saying their schools used them effectively to lengthen class periods, run after-school clubs, or allow teachers to plan lessons or review student data. But others said the extra time was squandered, leaving staff and students exhausted with little evidence of improved student outcomes to show for it. (Students’ pass rates on state tests stayed flat or declined at most “renew” schools in the first years of the program.)

The union also has complained that many teachers felt compelled to work the extra hours because those who refused to could be transferred to different schools. Under the terms of the original extended-day agreement, teachers were required to work an extra hour per day and attend trainings during the summer and some weekends.

In León’s email to employees, he said every extended-day school had set different work requirements and “none are consistent with the original design.” The longer days may also be contributing to high teacher turnover in those schools, he wrote, adding that principals of schools with regular hours told him they did not want to extend their hours.

Abeigon, the union president, applauded León’s decision to scrap the extra work hours.

“He came to the conclusion that we expected any true educator to reach: that the program was not working and was never going to work,” he said.

León said Thursday that he is now working on a new turnaround program. Once it’s ready, he promised to share the details with affected families before publicly announcing which schools are part of it — an effort to avoid the student protests that erupted when Anderson identified her “turnaround” schools.

He also said he was still considering whether he would ever close schools that fail to improve or to reverse their declining enrollments. Anderson’s decision to shutter nearly a dozen long-struggling schools continues to fuel resentment among her critics even years later.

“I think the whole idea of how much time does a school get to correct itself is a very important one and I’m going to need to be really reflective on it,” León said. “I’ve seen what closing schools does with people who do not feel that they were aware of it or a part of fixing it.”