When it comes to college, Newark faces a good news-bad news paradox.

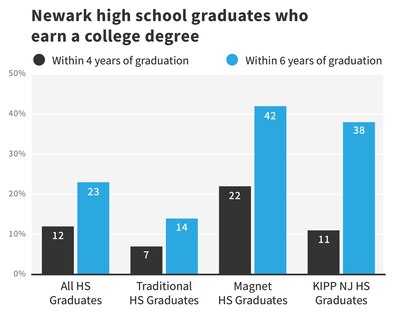

More students than ever are graduating high school and enrolling in college, according to a new report. Yet fewer than one in four Newark students earns a college degree within six years of graduating high school — leaving many with limited job prospects in a city where an estimated one-third of jobs require a four-year college degree.

Now, city officials are promising to build on the report. They want to ramp up the rigor of high-school classes and create more early-college programs to increase the odds of students entering college and leaving with a degree.

“How do we teach our children to perform — to graduate?” Mayor Ras Baraka asked at a press conference Wednesday to mark the official release of the report of Newark students’ college outcomes. “We got them in the door,” he said of students who attend college. “Now how do we make them stay?”

The city’s plans, to which Superintendent Roger León is lending his support, reflect a growing recognition that simply getting students into college is not sufficient — and can even backfire if they drop out before graduation, leaving them with college debt but no degree.

Until recently, the charge given to high schools in Newark and across the country was to foster “college-going cultures.” And these efforts showed promising results: On average, 51 percent of Newark Public School students who graduated high school between 2011 and 2016 immediately enrolled in college, up from 39 percent who did so between 2004 and 2010, according to the report by the Newark City of Learning Collaborative, or NCLC, and Rutgers University-Newark’s School of Public Affairs and Administration.

But entering college didn’t guarantee its completion. Of those students who started college straight after high school, only 39 percent earned a degree within six years, the report found.

As a result, educators and policymakers have begun to think harder about how to help students “to and through” college — to ensure they actually earn degrees. Toward that end, Baraka and the NCLC — which includes roughly 40 colleges, schools, nonprofits, and corporations — has set a goal of 25 percent of Newark residents earning college degrees or comparable credentials by 2025.

Today, just 19 percent of Newark adults have associate degrees or higher — compared to 45 percent of adults across New Jersey and 40 percent nationally.

Superintendent León, who began overseeing the city’s schools on July 1, said his main strategy for supporting these efforts will be to expose students to challenging work early on.

“If we don’t do something dramatically in classrooms to improve instruction and make it rigorous,” León said after Wednesday’s event, then students are “getting into college but they’re not completing it.”

For starters, León said he wants high schools to offer more college-level classes. In the 2016-17 school year, just 21 percent of Newark students were enrolled in one or more Advanced Placement or International Baccalaureate classes — compared to 42 percent of students statewide.

He also vowed to raise the quality of instruction in the district’s traditional high schools. Only 14 percent of their graduates earn college degrees within six years, compared to 42 percent of graduates from the city’s selective magnet schools, the report found.

To do that, León said he will create specialized academies within the traditional schools modeled on the magnets, which have specialized themes such as science, technology, or the arts. The academies, which will partner with colleges, will most likely feature admissions criteria similar to those of magnet schools, which select students based on their academic and attendance records, León added.

And, for the first time, all ninth-grade students this academic year will take the Preliminary SAT, or PSAT, León said Wednesday. An additional 1,100 eighth-graders who passed at least one of their seventh-grade PARCC exams will also take the PSAT when it’s administered on Oct. 10.

Since 2016, the district has provided the PSAT to all 10th and 11th-grade students. But León said that giving the test to younger students will focus their attention on college and help identity those who are ready for advanced classes. The PSAT is designed to help students prepare for the SAT, which is used in college admissions, and to qualify for National Merit Scholarships.

The district, which was under state control for 22 years until February, is getting some assistance in its effort to improve students’ college outcomes.

For instance, KIPP, the national charter-school network with eight schools in Newark, is sharing its strategies for helping students choose the right college with guidance counselors at three district high schools.

And the higher-education institutions in the Newark City of Learning Collaborative, including Essex County College and Rutgers University-Newark, plan to create more “dual-enrollment” programs that allow high-school students to earn college credits, said NCLC Executive Director Reginald Lewis.

“We’re all going to do a better job,” Lewis said, “of making sure that once Newark residents get in our doors, that we help them persist.”