After the final bell rang at Newark’s East Side High School on a recent afternoon and students surged toward the exits, Hannah Olaniyi hustled to her next class.

By 3 p.m., she was copying down the distinctions between prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells among 13 other seniors who had elected to take a college-level biology course after their normal school day.

Before long, she would have to rush in an Uber to her evening job selling sneakers at KicksUSA, then return home to cook dinner for her siblings and finish her homework. But for the next hour, her only concern was taking notes so she could pass the course to earn the credits that would lead to a college degree.

“It’s not that I want, I need to get a degree,” explained Olaniyi, who said her commitment to education came from her mother, a Nigerian immigrant who died of cancer last year. “Failure is not an option.”

Olaniyi is not alone in her quest for a college degree. On average, 51 percent of Newark Public School students enroll in college right after high school, a rate that has grown over time, according to a new report. Yet only 23 percent of Newark high school graduates earn a degree within six years of leaving high school, the report found, leaving them ill-equipped for an economy where decent-paying jobs are increasingly reserved for college graduates.

The early-college program that Olaniyi is part of at East Side, like those at a handful of other Newark schools, is an effort to close the degree gap by allowing students to earn college credits even before they have high-school diplomas. Through a partnership with Essex County College, a Newark-based community college, East Side students who qualify by passing a required exam can earn up to 64 college credits and an associate’s degree by graduation — a benefit offered by only 7 percent of programs like this in the U.S., according to federal data. And, unlike many programs, the cost of transportation, books, and tuition is free to students.

Such partnerships, often called dual-enrollment or dual-credit programs, have gained popularity across the country as a way to increase students’ odds of completing college by exposing them early on to college-level work and expectations and reducing the time — and cost — of earning a degree. Not only are dual-enrollment programs more prevalent in high schools than college-level Advanced Placement or International Baccalaureate courses, according to federal data, but they also have been found to serve a broader range of students than AP courses, which are more narrowly targeted to the highest-achieving students.

Some skeptics question whether college-level classes taught in high schools like East Side match the rigor of traditional college courses and have raised concerns that some colleges may not accept credits earned through dual-enrollment programs. But because New Jersey’s public universities must accept community-college credits, East Side officials say their early-college graduates, most of whom attend state schools, have saved thousands of dollars through the program.

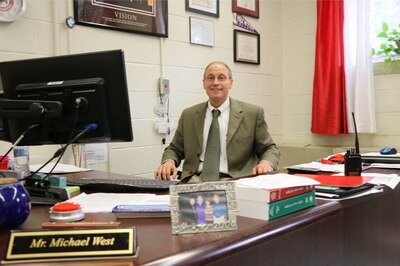

“Hard work pays off,” said Principal Michael West, repeating a mantra he tells his students. “And doors open because of this.”

Erika Baque, now a 22 year-old addiction counselor, found that to be true.

In 2012, she was a junior at East Side, Newark’s largest and most diverse traditional high school, when West launched the early-college program. Her parents, Ecuadorian immigrants who were adamant that their three children attend college, insisted that she apply.

At first, Erika was reluctant. Other students and even faculty members advised against it, saying AP classes were safer than a new program promising credits that colleges might reject.

“There was a lot of pushback from a lot of folks,” said West.

Still, Baque sat for the program’s entrance exam and interview and was admitted. Then the work started.

Each day, early-college participants take two roughly 80-minute liberal-arts courses in subjects such as sociology, art history, and biology. Most are taught by a qualified East Side teacher or adjunct professor at the school, which sits in Newark’s Ironbound neighborhood across from Independence Park. Usually one class per semester meets at Essex County College’s downtown campus, which East Side students ride to in a yellow school bus.

Overwhelmed by the burden of college courses in addition to their high-school classes, more than half of the 30 students in Baque’s cohort quit the program. West called those who stayed “The Fearless Fourteen.”

“I wanted to drop out like 50 million times,” Baque recalled. “I would go home and kick and scream and cry.”

Instead, she completed the program and, after graduating from East Side, enrolled at Montclair State University as the equivalent of a junior. Her experience at East Side had prepared her for the demands of college, she said, allowing her to earn a bachelor’s degree in psychology in just two years.

Now, she is earning a master’s degree in counseling while working at a residential addiction-treatment center in Newark. Meanwhile, her brother Erik, who completed East Side’s early-college program this spring, is studying civil engineering at Rutgers University-New Brunswick, while her youngest brother, Freddy, is a junior at East Side who has just started the program.

Erika still remembers West telling her, “It’s going to be worth it in the end,” she said. “And it was.”

Dual-enrollment programs are one answer to the problem of Newark students who enroll in college only to be tripped up by classwork, campus culture, or money, and drop out. Research has shown that dual-enrollment participants not only enroll in college at higher rates than non-participants, but they also tend to have smoother transitions to college, get better grades, and are more likely to graduate.

East Side requires incoming early-college students to take a “college success seminar,” which is being held at Essex County College this fall. Students learn about the financial risks and rewards of college, the basics of writing research papers, and “soft skills” like time management and teamwork.

This year, a total of 97 juniors and seniors are in the program — including, for the first time, 27 students who are still learning English, most of them Spanish-speaking immigrants from such countries as Columbia, El Salvador, and the Dominican Republic. (Another 32 students are taking some college classes but not the full load.) Essex County College waives tuition fees for the early-college participants, but East Side still pays about $3,200 per student, mainly for the cost of adjunct professors, out of its $16.6 million annual budget (based on 2016-17 figures).

West’s dream is to expand the program to include all 2,035 East Side students — a model employed by Bard High School Early College, a selective magnet school in Newark where all students can earn associate’s degrees from New York’s Bard College. But East Side’s program is limited by funding, which comes out of the school’s operating budget.

“We want to scale this and offer it to everybody,” he said. “The question is: How do we pay for that?”

Help may be on the way. Mayor Ras Baraka and a coalition of colleges and corporations has set a goal of increasing the share of Newark adults with college degrees from 19 to 25 percent by 2025. Reginald Lewis, the executive director of that coalition, called the Newark City of Learning Collaborative, said one strategy will be to expand the city’s dual-enrollment programs.

At East Side, it’s not hard to find students who would cheer that expansion. After a film studies 101 class one recent morning, three seniors explained why they believe the rewards the early-college program promises are worth the sacrifices it demands.

Gabriel De Oliveira said he had struggled in grade school. In the fourth grade alone, he recalled being suspended 10 times. But at East Side, with the encouragement of a ninth-grade English teacher, he began to take school more seriously, enrolling in an AP course, then the early-college program. Last year, he counted 60 nights when he stayed up past midnight completing coursework.

“I’m still learning,” he said. “But I feel like I’m stronger.”

Judith Zeta said the program has meant parting ways with friends when they go to hang out at a local cafe after school and doing homework on the train after her nightly 5:30-to-10 p.m. shift at a Hoboken restaurant. But she knows that when she earns her associate’s degree this spring and begins college ahead of schedule, it will ease the burden on her parents, who immigrated from Peru and work in construction and at a local hospital.

“They’ve made so many sacrifices for me and my brother,” she said. “This is the one thing I want to give back.”

And Hannah Olaniyi, the student who is helping to raise her siblings, said she decided after her mother died last year to transfer from a charter school to East Side solely for its degree program.

“That’s the whole point of me coming to this school,” she said. “If I don’t commit to this, if I don’t give it 110 percent, then I failed myself.”