Early this August, Yumar Wheeler was still making a living as an overnight security guard when he received an unexpected offer.

It came from the assistant principal of TEAM Academy, the Newark middle school that Wheeler had attended more than a decade earlier. He called Wheeler and asked: Would you like to become a science teacher?

Wheeler, who grew up in Newark and graduated from Fairleigh Dickinson University in 2016 with a degree in sports administration, had applied for other jobs at KIPP New Jersey, the charter-school network that includes TEAM Academy — but none of them involved teaching. He loved science and was intrigued by the idea of becoming a science teacher, a position many schools struggle to fill. Yet he was concerned about his lack of credentials.

When he went in for an interview the following week, the school’s leaders said not to worry — they wouldn’t just plop him in front of a classroom. Instead, they would place him in a paid, year-long residency where he would learn the craft of teaching by assisting the school’s sixth-grade science teacher while also taking classes on the fundamentals of instruction. Gradually, under the watchful eye of veteran educators, he would take on greater responsibilities until he was ready to lead his own class.

He accepted the offer and began attending TEAM staff trainings before his nightly security shift. On Aug. 30, less than a month after that fateful call, he officially started as a teacher-in-training.

“I was excited,” said Wheeler, 26. “I would compare it to a kid’s first day of school, or the night before Christmas.”

Wheeler is one of 20 aspiring teachers taking part in year-long apprenticeships at nine KIPP New Jersey schools in Camden and Newark, including TEAM Academy. Newark Public Schools runs a similar teacher-residency program in partnership with Montclair State University.

Such programs are still relatively rare — a 2016 study identified 50 teacher residencies nationwide, mostly run by urban districts or charter-school organizations. But they have generated considerable buzz as a promising alternative to traditional university-based programs, which are often criticized for providing only brief student-teaching opportunities, and to fast-track certification programs, such as Teach For America, where novice teachers with minimal preparation are put in charge of their own classrooms.

During residencies, would-be teachers — who typically did not study education in college — share classroom duties with a seasoned teacher while taking evening and weekend classes, which are often jointly taught by professors and district or charter employees. The residents receive stipends or full teacher salaries in exchange for agreeing to remain in the district or charter network for a number of years.

Research has shown that teachers who completed residencies are more likely than other beginning teachers to stay in the profession, which can reduce turnover and recruitment costs. Yet the programs are expensive, and some studies have found that residency-trained teachers were initially less effective in improving student achievement in math than other novice teachers.

KIPP’s residents take classes through the Relay Graduate School of Education, a relatively new — and controversial — institution that grew out of a teacher-training program founded by KIPP and two other charter-school networks. Relay’s Newark program trains teacher-residents in schools run by four charter-school organizations: KIPP, North Star Academy, Great Oaks Legacy, and People’s Prep. With financial aid from Relay and Americorps, residents can earn master’s degrees and teacher certifications for $6,500 or less in tuition costs and roughly $700 in exam fees, according to Relay.

Wheeler plans to enroll in Relay’s program in January. In the meantime, TEAM Academy is giving him a crash course in teaching. Two months into the job, he has already sat in on science department meetings, observed several teachers, watched instructional videos, and received coaching from Intisar Hatcher-Wright, an eighth-grade teacher and TEAM’s science department leader. Wheeler has also taken over the opening and closing portions of lessons led by his mentor and co-teacher, Desiree Perez.

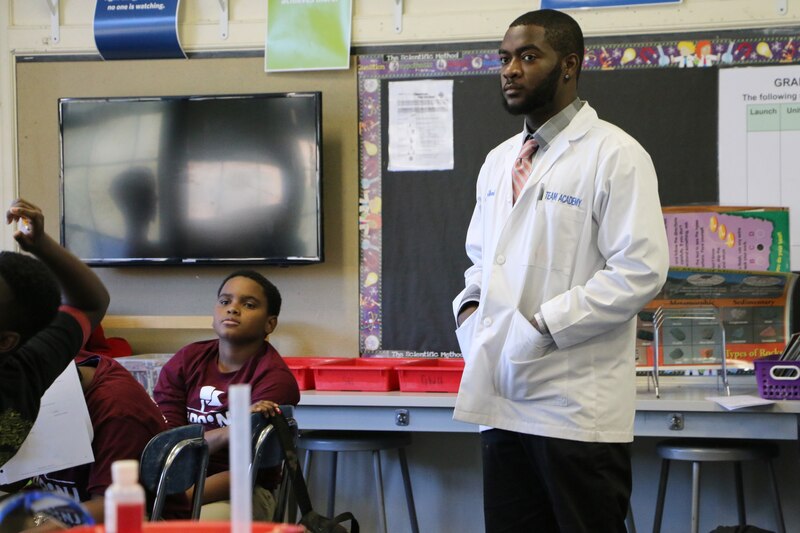

Still, there is no mistaking that he’s a rookie. On a recent afternoon, after a group of rambunctious sixth-graders scampered into science class, Wheeler — wearing the science department’s trademark white lab coat — gave a few handshakes and fist bumps, then stood off to the side while Perez expertly got their attention and described the day’s experiment. When it was his turn to speak, Wheeler uttered two sentences, then asked the students to discuss.

TEAM Academy School Leader Veronica Avery, who did a year-long residency before beginning her career as a Newark Public Schools teacher, acknowledged that she was taking a risk by investing in an aspiring teacher as inexperienced as Wheeler.

“At the end of the day, he could struggle and fall flat on his face,” she said, adding that she might ask Wheeler to continue as a co-teacher for an additional year if necessary.

But, she said, her own residency convinced her that novices can become experts through sustained practice and guidance. And Wheeler’s commitment to his hometown and its children, along with his deep ties to TEAM — besides being an alum, his brother is a paraprofessional at the school — had convinced her that he would work hard to become a skilled educator.

“Meeting him — knowing his heart was in the right place, that he was willing to put in the work — was everything,” she said. “I believe if you have the willingness, we can give you the skill.”

Whether because of his beginner’s enthusiasm or the background he shares with many students, Wheeler has already made an impression. After a recent science class, sixth-grader Rasul David said he and his classmates often turn to Wheeler for support.

“He helps students that have trouble at home or at school,” David said. “He treats us like we’re his own kids.”

Below is an interview with Wheeler and his coach, who is a veteran teacher. The interviews have been edited and condensed.

Yumar Wheeler

Tell me about the security job you held before you started teaching.

I was working security at a residential complex in Irvington, New Jersey. With that I was trying to take what I could get. We all know that bills never stop.

So I took on the security job and was working overnight. Maybe four hours sitting at a desk, and the rest walking, patrolling the property. I was walking like 10 miles a night. I liked it a little bit because of the exercise, but I would have much rather been sleeping.

What made you decide to return to KIPP after having been a student there?

I wanted to basically help the kids — and this goes beyond teaching.

Kids have this idea about college, and in sixth grade or fifth grade it can be so far away. But to see somebody who actually has been in their shoes, been in sixth grade, went to high school, finished college, and came back.

When I was going through school, not just at TEAM or [KIPP New Jersey’s high school, Newark Collegiate Academy] but also at FDU, just to see someone who looks like me being represented, was huge. The athletic director at the time when I was at FDU was a black male. I won’t sit here and say I’d never seen a black athletic director. But to sit in a class with somebody who was willing to give me guidance on what steps I could take to become an athletic director was huge and inspiring to me.

What has the residency program been like so far?

I’ve been learning how to manage the classroom, develop lesson plans, and basically shadowing teachers, viewing classrooms, seeing what key steps and skills work for them.

It’s been overwhelming, and it’s a lot. But I’ve been trying to stay organized and learning organization from a teacher’s aspect. It’s different from when you’re a student, and you have to turn work in to where you’re a teacher and you have to grade 150 papers that have to be in on time.

What have you learned from your mentor, Ms. Hatcher-Wright?

With Ms. Wright, the teaching workshops have been critical for understanding how students learn, demanding excellence from students, and 100 percent participation.

A lot of things I talk about I saw with her firsthand. Scanning the room, patrolling the room, making sure all kids are on task doing what they’re supposed to do.

Whatever situation you have going on outside of the classroom, or in another classroom, when we’re here, we’re all scientists, we’re all professionals, we’re all here to learn.

Do you think of any of your former KIPP teachers as model teachers?

[Shawadeim] Reagans [TEAM Academy’s former leader and math teacher], he’s one for sure. He was stern at the time. He was a lot younger [laughs]. There weren’t those gray hairs.

We’d be excited sometimes and create chants — like with multiplication tables. He used to dance then. On Fridays, we used to have, not a ceremony, but an ending with all the students. We used to sing songs. We’d all sit on the floor, campfire style.

Like many charter schools, KIPP is known for being a demanding place to work. What has that been like?

Since I’ve been co-teaching here, the latest I’ve stayed is 9:30, 10 o’clock. Me and a couple other teachers were here way after the cleaning staff of the building left. [We were] lesson planning and getting class ready for the week.

I don’t do that every day. A lot of the leadership stress self-care. They don’t want you to stay late. But me personally, I feel like I want to be prepared for the next day. I don’t ever want to be behind.

Intisar Hatcher-Wright

Hatcher-Wright studied teaching at Kean University’s New Jersey Center for Science, Technology and Mathematics, a five-year honors program that allows participants to earn both an undergraduate and graduate degree in teacher education. A Newark native with a dozen years of teaching experience, this is her third year at a KIPP New Jersey school.

You went through a traditional teacher-preparation program. Do you think all teachers should be trained that way?

There’s no doubt in my mind that you should definitely go through the traditional teacher prep. It just prepares you so much more thoroughly.

Nothing can replace four or five years of training. But can you give him the staples of that experience? Yes, you can try to do that.

It’s like being a doctor, a lawyer, anything else. Would you stick them in and be like, “You have a month to learn what you need to do, then you’re ready?” You wouldn’t do that. It’s not that extreme, but the point is that it’s a profession. There’s an art and a science to teaching.

As Yumar’s mentor, how are you trying to help guide him?

I try to give him support as far as how do we develop him from “Teaching 101” and the fundamentals to maybe what an experienced teacher would need. What can we do to develop him and make him a lifelong teacher or have the perspective of a nuanced teacher, as opposed to someone just thrown into the classroom and then you expect excellence.

We love our children, we don’t give up on them, and we provide them with a world-class education. If we’re going to be true to that, then we have to provide and develop world-class teachers.

What does that look like in practice?

We have weekly check-ins and, daily, we have minor touch points.

His latest string of observations — he had about three or four teachers a day that he had to go look at to gather some data about things like routines, systems, discipline. He gathered notes then we’d talk about, What did you see? What was most effective? Least effective?

How has he done so far?

It’s been a huge learning curve for Yumar. It hasn’t been easy for him by far.

But I will say that what has been maybe different in TEAM in the science department than he might have experienced otherwise is that I was really purposeful in protecting him and making sure he could take baby steps before he takes these larger steps.

The data shows that you need people that know the sciences, on top of what it takes to be a teacher of any discipline.

Is there a program you’re using or are you coming up with one yourself?

When I was doing graduate studies, a big focus area of mine was working with new teachers — the data behind it, the research behind it. My thesis was on new teacher-prep programs for science [teachers] and how do we make them most effective and help them in their early years when they’re feeling so vulnerable. How can we help them to defeat that, as well as really give them as much support to help them to equalize and find a way to get through the thickets and the weeds to become the most effective teacher as soon as possible.

What are the elements of good teacher prep, based on the research and your own experience?

Number one, you need a lot of exposure. Even if you want to be an urban teacher, you need to see the non-urban side.

You need a lot of practice, you need a lot of internships.

And one of the best things: They need a lot of support, especially after they get their so-called certification, and they take all their classes. Even then they need the most support — lesson planning, time management, classroom management — they just need support in every single way. And not to mention emotional management. They just need someone to talk to and be able to hear how they’re feeling.

Do new teachers get something from mentors that they can’t get from a college course on teaching?

Oh, yeah. It’s been proven that one of the sore spots of education professors is that many of them have not taught in elementary and high schools themselves. They’re professors but they’re not certified teachers. So this is something that the college world is really trying to grapple with.

When teachers come from the same background as their students, how does that benefit students — is it that they’re role models?

I’m not going to lie, that’s my go-to goal and motivator. I know when I was growing up, all of my friends, their parents worked, but they were blue-collar workers — many of them didn’t have degrees. With my family in particular, my mom didn’t finish her education, but she went. My father didn’t finish, but my three sisters were all biology majors.

You need to continue that. Also graduating from a STEM school at Kean University, knowing the disparity of people of color, women in general, and women of color [in science, technology, engineering, and math fields], that is a motivator for me. That’s why we have the whole science team wear lab coats. It may be small to others, but to [students], it signifies something big. It puts them in the mindset that this person not only teaches science, but he’s a scientist. Just for them to see that does make a difference.

What advice would you give a starting teacher?

Remember someone else has traversed the path that you’re about to traverse. So don’t think, “Can I do it?” You can do it. Don’t think, “Is this for me?” It’s for you.

I also impress upon them that whatever kind of classroom you want, you can make it. There’s no such thing as magic with classroom management. A lot of teachers, especially in urban areas, think that. Like they can do it, but I can’t do it. Again, there’s no can’t. Classroom management is a clear formula. If you do it right, it will work for anyone.

And continue to be a learner of your craft forever.