With one in three Newark students considered chronically absent last year, a team of researchers has set out to discover why so many students are missing so much school.

To solve that riddle, the team has held focus groups and surveyed high school students at summer school programs, churches, and supermarkets. Many researchers have conducted similar studies, but this team is different — it includes students interviewing their peers about their shared struggles with attendance.

“We’re speaking in a language they understand,” said Manuel Mejia, a sophomore at Rutgers University-Newark who attended Newark’s Arts High School. “We’re not here to research them as a separate group — we’re doing it to help all of us.”

The research team includes students from Newark’s traditional, charter, and county-run high schools, alongside students from Rutgers University-Newark. They are part of a Rutgers-based program, called New-Ark Leaders of Health, where students aged 14 to 21 research public-health challenges and propose solutions.

Earlier this year, the 17-member team decided to focus on absenteeism. They considered it a matter of public health because of the dire consequences for chronically absent students, who tend to have lower grades and higher dropout rates, and are at greater risk of entering the criminal-justice system and facing poverty as an adult.

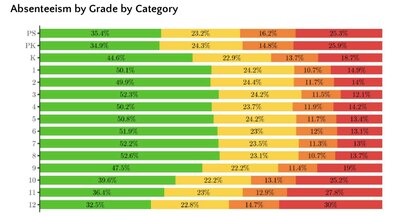

Newark suffers from unusually high rates of chronic absenteeism, which is defined as missing 10 percent or more of days in a school year — the equivalent of about a month of class. Unlike truancy, which refers to unexcused absences, this category includes anytime a student misses school — whether because of illness, a suspension, transportation difficulties, or other causes.

Last year, 33 percent of students were chronically absent. In the first three months of this school year, about 22 percent of students already are, with more likely to join them as attendance typically dips as the year wears on. And yet, because absences can accumulate gradually as students miss a few days one week then another day weeks later, many never realize the academic danger they’re in.

“I was basically chronically absent and I did not know,” said student-researcher Kutorkor Kotey, an 11th-grader at Bard High School Early College Newark, who said she missed several days one month. “Our main focus is to bring awareness to people.”

The research project was funded through a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation to the Abbott Leadership Institute, a Rutgers-based group that provides leadership training to Newark families and students, in partnership with the mayor’s youth and college-affairs office. The students who were selected to participate earn a small stipend.

In the spring, the team submitted a research plan to an institutional review board at Rutgers. After they tweaked a consent form to make it easier for high schoolers to read, the board approved it. By then it was summer, so the team targeted students in summer school and out in the community. They administered about 100 surveys and held two focus groups.

The student-researchers focused on high schoolers partly because those are their peers. But that is also the age also when chronic absenteeism spikes. Last year, nearly 40 percent of ninth-graders were chronically absent — a risk factor that greatly diminishes their odds of graduating on time.

To the average adult, that might sound like lots of students playing hooky. But the researchers knew from personal experience that many absent students would like to attend school — yet an array of obstacles often stand in their way.

“There’s always this narrative that people from Newark are perceived to be, from an outside perspective, lazy, poor, drug-ridden, and that’s why people are chronically absent,” said Simone Richardson, a Rutgers senior who helped lead the research team. “But what we’ve seen is that a lot of it is because of these oppressive structures.”

The researchers uncovered a heap of reasons why high schoolers miss school, from dentist appointments to unreliable city buses and concerns about gang violence on the path to school — or once they arrive. Often they are grappling with adult responsibilities, such as getting younger siblings to class or working after-school jobs, that make it hard to show up to school on time or at all.

One of the researchers, Eric Bellamy, who is in the 12th grade at Malcolm X Shabazz High School, described his own struggle to balance school and work. After classes end at 2:40, he rushes to a downtown seafood restaurant where he works as a cook and server from 3 to 9 o’clock, he said. It’s often 10 p.m. before he’s taken the bus home and can even think about homework.

As one of nine siblings, he said, he cannot rely on his mother to help pay for school-related expenses like a tuxedo and photos for prom.

“I’m not going to depend on my mom,” he said. “So I just have to thug it out and continue with the job.”

In some cases, schools themselves deter students from attending. Bellamy said school can sometimes feel like jail — “a cell that has more freedom,” as he put it. Other students mentioned strict uniform policies, unappetizing lunches, or ineffectual teachers that make them want to say away. Still others cited school policies that mark students absent after they have been late several times, and that block students with multiple absences from participating in extracurricular activities or even lead to suspensions, perversely adding to the days away.

“Schools don’t really get down to why that student is late,” said Israel Alford, a Rutgers senior who coordinates the research project. “Rather, they jump to, ‘Hey, let’s just punish this kid, maybe that will motivate them to come on time.’”

One of the main factors that the team heard time and again was mental health. Many students said they were coping with trauma or battling anxiety or depression. School guidance counselors are often overworked and under-qualified to address students’ mental-health needs, they said. Meanwhile, the schoolwork they must manage alongside their other responsibilities just adds to the stress.

Kayla Killiebrew, a 12th-grader at a charter high school run by North Star Academy, said she sometimes babysits her younger nephew on the weekends, which prevents her from completing her homework.

“Then I wake up in the morning stressed and I don’t want to go to school,” she said, explaining that she dreads having to tell her teachers she didn’t do her work. “There’s just so many factors in school that will add onto the stress I’m already having. So I’d rather just stay home and deal with it.”

The team is planning to conduct another round of surveys in high schools early next year, but first the group needs the district’s permission. They are hoping the new superintendent, Roger León, will sign off since he has said improving attendance will be cornerstone of his agenda.

Once the student researchers have finished gathering and analyzing their data, they intend to publish their findings along with policy recommendations. Their mission is to make sure that student voices inform any plan to improve attendance in Newark.

“Students know why they’re chronically absent,” Alford said. “The problem is that no one’s asking them.”