At Newark’s prestigious Science Park High School, students arrived at school this past Halloween playfully decked out as zombies, farm animals, and video game characters. But it was a teacher’s costume that stopped student-body president Sierra Etes in her tracks that morning.

A white physical education teacher wore a mask of Barack Obama, a red “Make America Great Again” hat like those worn by President Trump and his supporters, and a black T-shirt with the words, “Don’t Be A” over an illustration of a snowflake. “Snowflake” is a term often used by conservatives to taunt people deemed overly sensitive.

For Etes and some of her peers at the predominantly black and Hispanic school, the costume crossed a line.

“I was shocked,” said Etes, a senior who is black. “People were coming to me like, ‘Did you see it? Did you see?’ I didn’t know what to do.”

After causing a stir among students last year, the issue of the costume flared up at a packed meeting with parents and school leaders this month. Some parents, learning about the costume for the first time, were outraged, according to several attendees.

The students also recounted other incidents that did not involve the P.E. teacher, including non-black students using the N-word and another when black female students were told to remove their head wraps, which together have left some black students in particular — who are under-represented at the selective magnet school — feeling isolated and unwelcome.

Now, a vocal group of mostly black parents and students are calling for the P.E. teacher, Matthew Swartz, to be disciplined or removed from the classroom. A few plan to raise the issue of the costume, along with what they consider to be the administration’s inadequate response to that and other racial incidents at the school, at Tuesday’s district school board meeting.

“It’s a mess, and it’s been a mess for a long time,” said Celestine Swain, the parent of an 11th-grader at Science Park. “I’ve had enough.”

Swartz did not reply to emails, a voicemail, or Facebook messages about this story.

Some students who know Swartz said they saw the costume as a prank, not a mean-spirited provocation.

“He just did it as a joke for Halloween to have fun and get reactions,” said one 11th grade student, who is black and, like several other students, spoke on the condition of anonymity in order to discuss sensitive issues at the school. “Students, when they make racial comments, they have a negative connotation and they’re racist about it.”

But the parents and students calling for disciplinary action say the overtly political costume was inappropriate for a school setting and insensitive to black and Hispanic students at Science Park, including some first- and second-generation immigrants, who feel threatened by the president’s harsh rhetoric about immigrants and people of color.

Some also viewed the Obama mask, worn by a white person, as a type of blackface — a practice with a racist history that continues to spark backlash.

The controversy at Science Park highlights how explosive political speech in schools has become, amid deep polarization across the country. It also illustrates how, in the era of Trump and Black Lives Matter, some schools have struggled to respond when racially charged debates flare up in the classroom and students call out racism from the White House down to the schoolhouse.

The search for an appropriate response can be complicated by the fact that a far larger share of teachers and administrators are white than the nation’s students. In Newark, about 38 percent of school personnel are white, compared to just 8 percent of students.

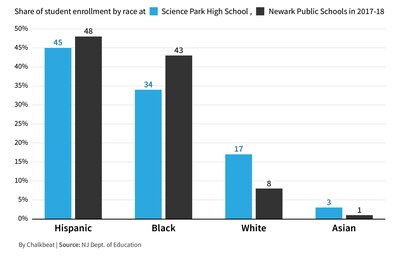

Science Park, which includes grades 7-12, is one of the district’s most popular and highest-performing schools, where students are admitted based on test scores, grades, and attendance records. About 45 percent of Science Park students last school year were Hispanic, which was just below the district average, while over 20 percent were white or Asian — more than double the district rate. Just over a third were black, compared to 43 percent districtwide. Many of the parents now speaking out about the school’s culture have been calling for admissions changes to draw more black students to the school.

At Science Park, the administration has taken steps to address students’ complaints. The principal, Kathleen Tierney, told Swartz to remove the mask and hat on Halloween after some students reported it to her, according to the students. (At the meeting, she said confidentiality rules prevented her from saying more about her interactions with Swartz, attendees said.)

Tierney and a district spokeswoman did not respond to requests for comment.

The administration also surveyed students and parents about the school’s culture. And Tierney, who is white, allowed teachers and student-leaders, including Etes, to organize a series of school-wide discussions this year about race, sexuality, and gender.

But critics say the steps are too small and came only after prodding. The Halloween costume, they say, was a missed opportunity for the administration to take a public stand against behavior that causes students of any race or gender to feel disrespected.

“It’s like the students’ emotions were minimized and literally swept under the rug,” said Etes. “Honestly, as a student, I feel like, ‘Why am I here?’ sometimes.”

On Halloween, Swartz’s costume drew immediate reactions. Students quickly began chattering and texting about it; one person posted a photo of the outfit on social media with the disapproving caption, “this ain’t it.” Etes and another student soon reported the costume to Tierney.

Later that day, Swartz posted two photos of himself in the costume on Facebook with the message, “Happy Halloween!” (The post was no longer publicly visible last week.) In comments below the post, Swartz said the costume had prompted classroom discussions about both Trump and Obama — “Fair and Balanced!” he wrote, using the former tagline for Fox News.

When someone wrote that the costume would get Swartz fired, he responded: “I wore it to work, kids laughed, teachers laughed, a few people cried! Lol.”

In interviews outside the school on Friday, several students, who declined to give their names, said they had found the costume offensive — or “super inappropriate,” as one 12th-grader put it.

Some also said Swartz had made off-color remarks to black female students in the past. Etes said that when Swartz was her P.E. teacher during her freshman or sophomore year, he referred to her hair as “unbe-weave-able,” a reference to hair extensions. Other students and faculty members, interviewed separately, said they had heard about his commenting on black students’ hair. Faculty members have reported remarks Swartz has made that they consider inappropriate to the administration, according to sources at the school.

Several students said they were surprised that Swartz did not appear to face any public consequences after wearing the costume, and that he remains in the classroom.

“I just thought, ‘Why is no one punishing him for this?’” one 11th-grader said. “Like, how is this allowed?”

A few students said they found the costume inappropriate, but still assumed it was meant as a joke. They noted that Swartz also coaches the track team and is well-liked by many students. When a parent called Swartz to complain about the costume after learning about it at this month’s school meeting, Swartz apologized for wearing it, said the parent, Kevin Maynor.

John Abeigon, president of the Newark Teachers Union, said Swartz had worn the Obama mask before without incident. He dismissed the current controversy as a non-issue fueled by a “vocal minority” of students and parents. He said he was not aware of any disciplinary action taken against Swartz, who apologized to the principal, though not in a public way to students.

“He’s already apologized if he’s offended anyone — but he shouldn’t need to apologize,” Abeigon said. “It’s the United States of America, and we should value opinions whether we agree with them or not.”

Top district officials appear to be aware of the controversy at Science Park.

Board member Leah Owens, who attended the March 5 meeting at the school, declined to discuss the specific incidents, but said, “We need to focus on the climate and culture of our schools.” Etes, the student-body president, said she told Superintendent Roger León about the costume when she met him earlier this year but has not heard from him since.

Last year, a district official called reports of racial tensions between students “alarming.” The official, who has since stepped down, said the district was investigating the situation and would send in an outside expert to help ease tensions.

That spring, the school gave anonymous surveys to students asking if they had ever experienced discrimination at Science Park or felt unsafe, and held a town hall meeting on cultural sensitivity that students helped plan.

This year, Etes, other student leaders, and several faculty members organized forums on racism, sexism, and homophobia, which included brief lectures by teachers followed by student discussions. While happy for the opportunity, some of the student-leaders questioned why they, rather than the administration, had to take the lead in planning the forums.

A faculty member, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, acknowledged the students’ efforts but also gave the administration credit for responding to students’ demands and carving out class time for the forums.

“I do see them working hard,” the faculty member said. “I think the problems are complicated.”

Yet, earlier this month, an administrator sparked a whole new racial controversy.

During lunch, a vice principal told 12th-grader Aishat Jimoh and other black female students to remove their head wraps because they violated the school’s uniform policy, according to Jimoh. Jimoh, who is Muslim, wears a headscarf on some days for religious reasons. But she and other students also wear head wraps as symbols of black cultural pride.

They argued that the administrator had singled out black students in enforcing the school’s typically lax dress code. In response, Jimoh organized a protest where other students wore head wraps to school and posted pictures on social media.

After the protest, Principal Tierney set up a meeting between Jimoh and the vice principal, who apologized, Jimoh said. (Officials in other districts have also apologized for banning hair wraps after learning about their cultural significance.)

Jimoh and some parents said the incident highlights a lack of cultural awareness among certain school staffers, which they said has contributed to the school’s racial tensions.

“There’s a misunderstanding or no understanding whatsoever” about certain aspects of black culture, said Kevin Maynor, whose daughter is in the 11th grade. “You’ve got to learn the culture.”

Jimoh agrees. She said she and other student activists are “genuinely tired” of having to call out racist behavior at the school, then having to explain to their peers and administrators why it was racist.

“They need to be enlightened about what it’s like to be a black person inside Newark and Science Park,” Jimoh said. “They need to be knowledgeable about that.”