Newark’s new schools chief has big plans for the district’s $1 billion budget — but he needs your support.

Superintendent Roger León unveiled his new administration’s first budget proposal this week, which included plans to restore programs for gifted students and adult learners, reopen shuttered schools, and replace the teaching materials used in classrooms. To help fund those initiatives, he asked voters to approve a 2 percent property tax increase next month — the first time Newark residents will vote on the district’s budget in over two decades.

“We are asking to have the citizens of Newark to vote yes on the budget,” León said at a Wednesday evening presentation. “These are dollars and programs and services that our students have longed for, that they need.”

León’s presentation was long on promises but short on details, which he said would be fleshed out in a strategic plan later this year. But even as he sketched out his vision for the district, he also described financial threats that could imperil his plans.

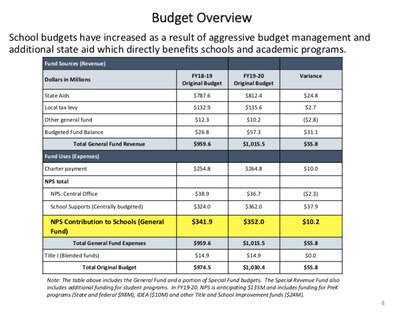

About a quarter of Newark Public Schools’ revenue next school year will go to charter schools, whose funding flows through district budgets in New Jersey. The district budgeted for a $10 million increase in charter costs. But if Newark’s charter enrollment grows to its full projected size in 2019-20 — a possibility that officials acknowledge is unlikely — the district will come up $24 million short. It’s a serious enough concern that León traveled to Trenton Wednesday morning to ask lawmakers for more money.

Newark schools are getting a 3.15 percent boost in state aid this year, part of Gov. Phil Murphy’s plan to gradually increase education spending. Yet, as León pointed out to the state assembly members, that raise is smaller than last year’s and still leaves the district with $174 million less than what it is owed by the state, according to a funding formula that has not been properly enacted for nearly a decade. At the same time, the district’s enrollment grew by about 1,000 students this year, León said.

Meanwhile, the district faces several legal settlements and penalties incurred by previous administrations — including a $48 million fine from the IRS — that could come due unless some other remedy is found. As León told lawmakers, he inherited legal challenges “that would scare most school districts.”

The district managed to balance next year’s budget, in part by ending some after-school programs and cutting more than two-dozen unspecified “school support” positions, officials said. But more drastic measures — including hundreds of teacher layoffs — could become necessary if the district’s worst fears materialize, such as the greater-than-expected charter growth or the massive federal fines, officials warned in their pitches for more state aid and higher taxes.

“It’s means closing schools,” León said at the Newark hearing. “It means high unemployment.”

Those worst-case scenarios do not appear probable, at least in the near future. Valerie Wilson, the district’s school business administrator, noted that charter schools do not usually reach their full projected enrollments. And León acknowledged that the doomsday scenario of school closures and widespread layoffs are “not where we are right now.”

In recent years, the district has faced gaping budget holes due to flat funding under former Gov. Chris Christie, declining enrollment, and rapid charter school expansion. Léon’s predecessors responded by closing schools, cutting staffers, and scaling back services for students and parents — moves meant to save money, as well as eliminate some positions and programs that were deemed ineffective.

Now, León wants to reinstate some of those personnel and programs.

His plan calls for a reorganization of the district’s central office that would reboot 11 departments — including English and math, gifted and talented, and career and technical education — that were ended or consolidated by previous administrations. León, who worked in the school system for 25 years before becoming superintendent last July, said he watched many of those departments disappear over the years.

The timeline of that overhaul is unclear, as is the cost and whether it will require new hires. Budget documents simply say “pending availability of funds.”

León, who has tended to announce big plans without sharing many details, declined to be interviewed. He and Wilson referred questions to a district spokeswoman, who did not respond to a list of detailed queries.

The plan León outlined Wednesday also allocates $5 million to reopen several shuttered schools, including Harold Wilson and Newton Street, currently occupied by central-office employees. Those employees would return to the district’s downtown headquarters, requiring a $3.6 million expansion of those offices.

He also proposed numerous academic investments, including $10 million for new curriculum materials and $10 million for 107 additional teachers along with other school workers. He vowed to bring back adult education, such as Spanish and GED courses, and to revamp the district’s special education and bilingual programs.

Both educators and non-instructional staff, such as school guards and cafeteria workers, will receive new training, León said. A new “superintendent’s leadership academy” will help top teachers and administrators move into bigger leadership positions, he added. A budget document lists topics the academy will cover, including Microsoft Office software, telephone and email etiquette, and time management.

León told lawmakers his plans will jumpstart student learning, which he said remains limited even after aggressive reform efforts by his predecessors. (Before a downtick last year, the district’s test scores and graduation rate rose steadily for several years.)

“The academic achievement levels in the district after multiple superintendents are in dire need of improvement,” León said, “and require significant investments in curricular materials, programs and services to begin the road to recovery.”

The Newark school board approved León’s budget on Wednesday. Now, Newark voters will decide whether to sign off on a $2.7 million tax hike to help fund León’s plan on April 16, when they will also choose three new school board members. If they vote down the tax increase, which would raise education-related property taxes to about $1,953 for the average homeowner, then the city council and possibly the state education commissioner would decide whether or not to allow the increase, officials said.

Danielle Farrie, research director at the Newark-based Education Law Center, said the district will remain “dramatically underfunded” based on the state formula — even if it gets slightly more state aid and local revenue this year.

“Even if they aren’t making cuts,” she said, the district is “still not at level of resources where they should be.”