School closures, mass protests, and a boom in charter schools — the past decade was a tumultuous one for Newark schools. Yet, today, Newark students are better off academically than they were before.

That’s the conclusion of a new report that looks at test scores and graduation rates at Newark’s traditional and charter schools from 2006 to 2018. It found that Newark’s ranking among other high-poverty districts based on its state test scores rose significantly during that period, as did its graduation rate. (Despite those long-term improvements, Newark’s citywide test-score growth and district graduation rate dipped last year.)

The report was produced by MarGrady Research and funded by the New Jersey Children’s Foundation, a new nonprofit that promotes collaboration between traditional and charter schools.

The period covered in the report was a time of contentious education change in Newark, which included the rapid expansion of the city’s charter sector and a district overhaul engineered by former Gov. Chris Christie, then-Mayor Cory Booker, and Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg.

A separate peer-reviewed study published last year by Harvard researchers, who had access to student-level data, concluded that the district overhaul eventually improved students’ annual growth on English tests but not math. The new report, which relied instead on publicly available school- and district-level data, is careful not to attribute students’ progress to particular policies.

“In this study, we do not argue that any single reform or set of reforms caused the gains documented here,” write the authors, Jesse Margolis and Eli Groves. “We simply argue that the gains happened, they are real, and they are meaningful.”

Here are the key takeaways from the new report.

Newark students — and low-income students in particular — made progress on state tests

Test scores have been on the rise in Newark in recent years.

The percentage of Newark students who met the state’s expectations on the annual English and math tests grew from 2015 to 2018. Both traditional and charter schools made strides on the tests, which students take in grades three to eight.

But Newark’s charter schools, which educate a third of city students and are among the top-ranked urban charter schools in the country, collectively outperformed the city’s traditional schools. For instance, about 35 percent of district students hit the state’s target in English last year, compared with over 60 percent of charter students — a proficiency rate that exceeded the state average. Newark’s charters enroll fewer students with disabilities and those still learning English, who tend to have lower test scores, than its traditional schools.

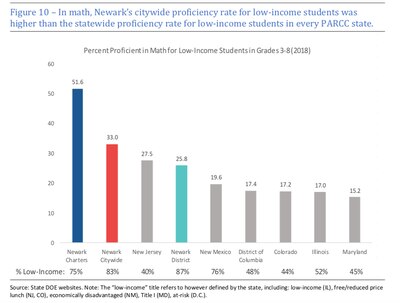

Newark also got a larger share of low-income students to pass the tests than did the District of Columbia and the five states — Colorado, Illinois, Maryland, New Jersey, and New Mexico — that use the tests, known as PARCC. Newark’s charter schools drove the city’s high performance. But the traditional schools still had more needy students pass the PARCC tests than other large districts, including Baltimore, Chicago, Denver, and D.C.

The report also compared Newark’s test score performance to 36 other high-poverty districts in New Jersey. Combining traditional and charter school scores, it found that Newark had climbed from 23rd place among those districts in 2006 to eighth place on the English tests and ninth place in math by 2018.

More black students attend high-performing schools

The share of black Newark students in high-performing schools quadrupled from 2006 to 2018.

The report defines those schools as ones that beat the statewide proficiency rate on the annual English and math tests. The increase is largely a reflection of the growth of high-performing charter schools, which enroll a disproportionately large percentage of black students.

In 2018, 54 percent of black charter-school students attended an above-state-average school. Just 4 percent of black traditional-school students attended such schools.

Graduation rates grew

Newark’s citywide four-year graduation rate climbed 14.5 percentage points from 2011 to 2018.

The analysis starts at 2011 because that’s when the state started using its current methodology to calculate graduation rates. The statewide graduation rate also grew, though Newark’s rose faster.

Mark Weber, a lecturer at Rutgers University and an education policy analyst, has noted that other high-poverty districts made similar graduation gains during that period. He also argues that the widespread practice of allowing high-school students to earn credits through online courses calls into question whether the graduation gains reflect real improvements in student learning.

Enrollment is up, too

Newark reached a milestone last year: For the first time, more than 50,000 students attended the city’s public schools — traditional and charter.

Over much of the past two decades, the district’s enrollment steadily declined — from 43,000 students in 1999 to 34,000 students in 2018 (that number excludes preschool). During the same period, charter enrollment ramped up from 3,000 to 17,000 students.

But in the past three years, charter growth has slowed while the district’s enrollment has held steady. And this year, district officials said they added about 1,000 students.

Some schools still struggle

Many Newark schools showed big improvements over the past decade — but not all of them.

The report found 25 schools with lower proficiency rates on the 2018 state tests than the average among high-poverty districts in New Jersey. Those schools also had lower-than-average growth rates on the tests.

Those low-scoring, low-growth schools enroll 15,000 students — about 11,500 in traditional schools and 3,500 in charters.

And while Newark schools overall have improved, the city still ranks in the 14th percentile among all New Jersey districts based on state test scores. But even that ranking, which includes far wealthier districts, represents an improvement from 2006 when Newark was in the fourth percentile.

“Where few Newark students in 2006 had hope of attending a high performing school, a substantial and growing number now do,” the report says. “But there remains much work to be done.”