One balmy morning this July, Yamin Reddick sat down in front of a computer in a windowless college classroom and braced himself for the day ahead. At 8:30 a.m., another eight-hour round of classes would commence, followed by homework late into the night. Then a few hours of sleep, wake up, and repeat.

That grueling schedule had become Reddick’s life ever since he earned a diploma from Newark’s Central High School in June and, days later, started a six-week summer program at Rutgers University-Newark. Known around campus as “academic boot camp,” it’s designed to prepare disadvantaged high school graduates for the rigors of college.

At Central, where Reddick managed to get decent grades even as he traveled the country for speech and debate tournaments between after-school shifts at the local Wendy’s, he told anyone who would listen that he was headed to Rutgers-Newark. Just a mile from his home, it’s the public university where his mother once enrolled but dropped out after giving birth to Reddick and his twin sister.

Reddick intended to pick up where his mother had left off. He could already envision the “Black Excellence” student group he would found at Rutgers-Newark before launching a career in community organizing and politics — just like his hero, Cory Booker. If he were elected, he’d get the lead out of the city’s water and make sure every student attends an excellent school. He believed his own success would set straight all the people he’d seen scoff at Newark. And he wasn’t afraid to voice his grand ambitions: “I want to become part of Newark’s history.”

But before he could rise to become Newark’s next great leader, he had to earn a college degree. And before he could start on the path to a degree this fall, he needed to pass his summer classes. Otherwise, his college career at Rutgers could end before it even began.

“Our final exam is exactly one week from today,” his summer math instructor, Jose Garcia, told Reddick and his classmates that morning.

Reddick logged onto the course’s online learning program. He has always struggled with math, and his scores on a placement test landed him here — a remedial class covering fundamentals like fractions, geometry, and equations.

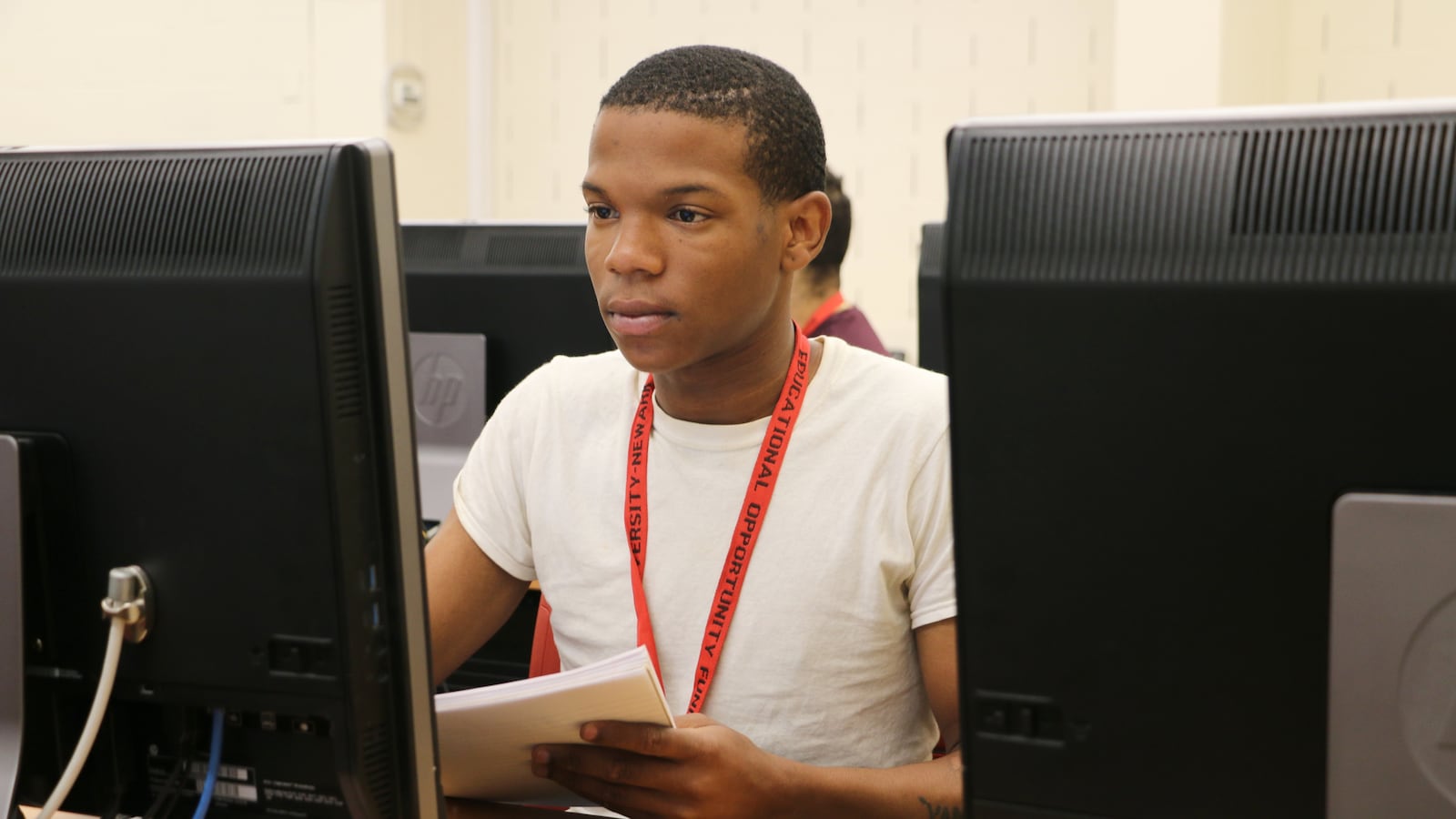

Reddick got to work. Babyfaced and exuberant, he can seem younger than his 19 years. But now he was stern-faced, writing out problems with pen and paper — unlike high school, no calculators allowed — as he raced to complete coursework that was due in just a few days.

He answered a string of division problems correctly. “Excellent progress — keep it up” flashed on screen. But then a section on multiplying positive and negative fractions broke his streak. He rubbed his eyes. Then came questions involving percents and decimals. He asked for help.

“Mr. Garcia, it says I got this wrong,” Reddick said. Over his white T-shirt hung a red Rutgers lanyard bearing his student ID, on loan for the summer.

Garcia helped him find the solution. But a few minutes later, class was over. Many of his classmates had completed their problems. Reddick still had 113 left to go.

College, to say nothing of the degree he believes will unlock the life he dreams of, still seemed a long way off.

The promise

A decade ago, when Reddick was still in grade school, he was standing outside his apartment one day when a black SUV drove by. A tiny Reddick waved. The SUV’s rear window lowered and a smiling man waved back. It was Newark’s new mayor, Cory Booker.

When he took office in 2006, Booker promised to revitalize the aging city, where nearly one in three children lived in poverty. And he would transform its troubled school system, which about half of students passed through without earning diplomas. He subscribed to a doctrine of education change that would find disciples from Wall Street to the White House, which held that if traditional schools were thoroughly overhauled and new charter schools opened, poor students would graduate high school, earn college degrees, and escape poverty.

The superintendent Booker helped recruit, Cami Anderson, laid it out in 2013: “The first thing is to define success. And that’s pretty simple. Every kid of school age in Newark is in a school that puts him or her on the path to graduate from college.”

The goal of getting all students to college was rooted in the reality that higher education — despite its rising costs — remains this country’s main engine of upward mobility. Yet only 60% of students who enroll at four-year institutions earn a degree within six years. The rate is even lower for black, Hispanic, and low-income students.

In Newark, more students are entering and completing college today than when Booker first became mayor, according to an analysis by researchers at the Newark City of Learning Collaborative and Rutgers University-Newark. Yet even with those gains, less than half of Newark graduates who head straight from high school to four-year colleges earn degrees within six years. At the district’s traditional, non-selective high schools — like the one Reddick attended — just 16% of graduates who immediately enroll in college earn bachelor’s degrees six years later.

Booker is now running for U.S. president, while many of the children who grew up during his mayoralty are entering college. Newark has a new mayor, Ras Baraka, a former high school principal who has made it a goal to get more Newark residents to attain degrees. The school system’s new superintendent, Roger León, has signed on, recently promising to pair all high school graduates with mentors to shepherd them through college.

Newark needs you. Everywhere needs you.

One of the leaders of this citywide effort to boost college completion is Rutgers-Newark, long touted as one of the most diverse national universities in the country. About two-thirds of its black, Hispanic, and low-income students graduate in six years — well above the national averages for those groups. Unlike other colleges that enroll similar student populations, there is virtually no graduation gap between its black and Hispanic and its white and Asian students, or its poor and non-poor students.

The summer program Reddick is part of is one component of the university’s Educational Opportunity Fund program, a longstanding statewide effort to help low-income students complete college. It’s one of the many ways that Rutgers-Newark tries to get students who face the longest odds of graduating to cross the finish line.

“I tell them: I can’t afford for them to fail,” said Sherri-Ann Butterfield, Rutgers-Newark’s executive vice chancellor. “As a country I can’t, as an institution, as a city. Newark needs you. Everywhere needs you.”

A Newark education

The path to a college degree begins long before students ever step foot on campus.

Reddick’s journey — which, in some ways, is also the story of education in Newark over the past two decades — began at Camden Street School. Housed in a red-brick building around the corner from Reddick’s apartment in the city’s impoverished Central Ward, the school educated three generations of Reddick’s family: his grandparents, his mother and her twin brother, and Yamin and his twin.

The school felt like home to Reddick. His grandfather would drop by to chat with the security guards and check on Reddick and his sister. His kindergarten teacher, who had taught his mother years before, took Reddick to sing at her church on the weekends.

“They all knew my family,” Reddick said. “They had me on the push to always do what I had to do, to always be that scholarly student.”

Then, in 2011, when Reddick was in fourth grade, Cami Anderson came to town. Under orders from Booker, then-Gov. Chris Christie, and Mark Zuckerberg — the Facebook CEO who had committed $100 million to improving education in Newark — the new superintendent embarked on a sweeping overhaul. It involved the closure of several low-performing and under-enrolled schools and the restructuring of others, including Camden Street. Before long, the school’s principal and many teachers had been replaced.

“Everything kind of fell apart. The school wasn’t what it was anymore,” Reddick recalled. “I just felt like somebody robbed us.”

The disruptions continued. Reddick left Camden Street after fifth grade and bounced from a new district school to a charter school, a type of school that proliferated under Booker. During eighth and ninth grade, his family moved to South Carolina, back to Newark, then to Elizabeth, N.J., with Reddick landing in a new school at each stop. In Elizabeth, he attended a diverse arts high school, where he learned to play guitar and sang Taylor Swift songs with friends of different races — a first after years of segregated, all-black schools.

“It felt like ‘High School Musical,’” he said.

But then his family uprooted again, returning to Newark where his mother worked as a clerk in the county welfare office. As he entered his sophomore year, Reddick enrolled at Central — the high school down the street from his apartment where Mayor Baraka had once been principal and Reddick’s mother was an alum.

The school’s academic record wasn’t great, but Reddick believed he would be comfortable there, safely removed from the bullying he had occasionally endured over the years on account of his sexuality — he identifies as gay — and his outsize personality. “Some people,” he said, “when they look at me, their first impression is: I’m doing too much.”

At orientation, he heard about the speech team, a variation of debate where students perform humorous pieces, dramatic readings, poetry, and more. A natural performer, Reddick decided to join. For the next three years, he practiced until 6:30 or 7 most school nights, and competitions filled his weekends.

The team traveled to tournaments at Harvard and the University of Pennsylvania. At the University of Kentucky, they marveled at the sophisticated-looking students striding across the lush campus and thought, “That’s going to be us.”

Yet they could not escape the sense that something different, often something lesser, was expected of them because of who they were: black students from a high-poverty school in Newark competing against many affluent white and Asian teenagers, whose schools (unlike Central) offered whole classes on speech and debate.

Reddick responded by perfecting his craft. “You got to come prepared,” he said. Central’s coach, Dennis Philbert, often had his students play against expectations, reading European works in German and Russian accents. But in his senior year, Reddick decided to put racism and the harsh policing of black people in the spotlight.

He drew on his childhood memory of police officers storming his apartment, guns drawn, in pursuit of one of his family members. And, more recently, the time when an officer aggressively questioned him as he hurried home from school in the rain. He began performing a piece about Trayvon Martin and a poem called “The War on Black Boys.”

“I wanted to make a statement,” he said.

Back at Central, Reddick made himself into a leader. He joined a group that gave policy recommendations to Superintendent León, and got elected as Central’s student body president. Sometimes, he would stand in the hall and tell his peers to get to class. “You would really think Yamin worked for the school,” said Reddick’s friend and speech teammate, Zawadi Kabazimya.

Meanwhile, he put in hours at a fast-food restaurant and a supermarket, and helped care for his four younger siblings. With his mother working full-time and his father not closely involved with the family, Reddick dropped off his siblings at school and tried to set an example for them.

“I want them to know that if you know what you want in life, if you have a mission, you attack it while you can,” he said. “You do it now — don’t wait until later.”

Like at Camden Street, Reddick found a second family at Central. His classmates encouraged him, and the staff cared for him. Yet there was no denying that academic achievement was low at the school, where most students are poor and about 30% have disabilities. In Reddick’s junior year, nearly two-thirds of students were chronically absent and just 2% passed the state’s math tests. Only a third of Central graduates enrolled in college that year.

The real thing comes now.

Reddick maintained a 2.5 GPA, which ranked him 60th out 152 students in his senior class. The school offers few college-level courses, but it allows students to take classes at a local community college. Reddick passed several classes there and aced a speech class. But he failed the college-level writing and Algebra courses.

Still, Reddick had reason to celebrate when he graduated this June. He had worked diligently in and out of class, and made a name for himself — his principal called him a “superstar.” He had learned resilience from his mother, Linda Williams, who survived homelessness and domestic violence, and now pushed her children to excel in school. “Because of your race and where you’re from, people are going to think less of you,” she said. “You have to show them who you are.”

As Williams watched her son walk across the stage that day, she was overcome with pride. But she could not help but think of the next challenge that stood before him: college.

“The real thing comes now,” she recalled thinking. “We got to attack these years.”

Make-or-break summer

On a Saturday morning just over a week after graduation, Reddick found himself sitting in an immense room on Rutgers-Newark’s campus alongside more than 100 other recent graduates. All were hoping to be the first in their immediate families to earn a four-year college degree.

It was orientation day — not for college, but for the program that promised to help get them through college.

The Educational Opportunity Fund, or EOF, program was established in 1968 in response to deadly unrest in Newark the previous year, when black residents raged against the political oppression and police brutality they had long endured. The statewide program was designed to steer “educationally and economically disadvantaged” students to colleges, such as Rutgers-Newark, which at that time was 95% white in a majority-black city.

But the campus was slow to enact the program. So, in 1969, members of the university’s Black Organization of Students barricaded themselves inside a classroom building that they dubbed “Liberation Hall” and demanded that the school recruit more black students and faculty members. After a three-day standoff, officials agreed to implement EOF in earnest. A half-century later, about 45% of Rutgers-Newark students are black or Latinx, earning it the top spot on U.S. News & World Report’s ranking of the most diverse national universities for much of the past two decades. (It’s now tied for second place.)

Leading Reddick’s EOF orientation that day in late June was Dean Deborah Walker McCall. She has a commanding presence tempered by a warm smile; she calls herself the program’s “mama bear” and the students her children. A native Newarker, she had taken advantage of EOF’s services years ago as a student in Rutgers’ College of Nursing even though she wasn’t technically part of the program. “I’ve always been team EOF,” she said.

Years later, she returned to direct Rutgers-Newark’s EOF program out of a deep belief in its premise: that when given the proper support, students from poor families and under-performing schools can do just as well in college as their more privileged peers. “Watching students who were told they can’t demonstrate that they can” had convinced her of that, she said.

Today, Reddick and his peers at Rutgers-Newark are among some 13,500 students at more than 40 New Jersey colleges and universities who participate in EOF programs. To be admitted, students must come from families with incomes that are no more than double the federal poverty threshold and have grades or test scores below the participating institutions’ normal cutoffs. Using state funds, the institutions provide EOF students with counseling and mentoring, small grants to help cover expenses like books and housing, and academic preparation in the form of intensive summer classes before they officially start college.

But all that extra support cannot erase the difficulties faced by many EOF students, who tend to lag behind their peers academically when they enter college. At Rutgers-Newark, just half of EOF students graduate in six years, according to 2017-18 data provided by officials.

At the orientation, Reddick listened closely as the dean laid out the summer program’s requirements. Students would attend class from 8:30 a.m. to 5:20 p.m. Monday through Thursday, with tutoring on Fridays. If they did not earn at least a combined C average in their classes, they risked not being admitted to the university that fall.

“You’re going to be stretched and pulled in ways you’ve never been before,” Walker McCall said she told the students.

As Reddick left that afternoon, his new Rutgers ID and summer schedule in hand, he was struck by how the deans and counselors had addressed the students. In high school, the staff had dealt delicately with the students, who were, after all, still teenagers finding their way in the world. Reddick still felt that way, yet the adults here seemed to view him differently — as an adult himself, fully in charge of his actions and his fate.

“This is going to be on me,” he thought. “I’m responsible for everything.”

That evening, Reddick’s mother and grandparents hosted a surprise party for him. Surrounded by balloons in Rutgers’ red and black, his extended family feasted on shrimp and ribs and toasted his accomplishments. His grandfather, Louis Williams, served cake that he baked for the occasion.

After all that excitement, Reddick overslept the next morning. He missed the second day of orientation.

The next day, classes began. Just as they were starting, Dean Walker McCall pulled Reddick into an empty room. Where had he been on Sunday? And why hadn’t he called anyone? Everything got blurry, but Reddick recalled hearing next: “We might have to let you go.”

He began crying. It hadn’t sunk in until that moment that if he didn’t meet the requirements, he could lose his spot in the program — and at Rutgers. He called his mother, who quickly arrived to meet with the dean. Walker McCall agreed to let Reddick continue. But the message Reddick left with was clear: “You’re an adult now,” he said. “If you don’t show up, you don’t get the job.”

After that inauspicious start, nothing really got easier. Reddick and his peers shuffled from math to English to geology class each day. They also took a course that taught them study strategies and how to interact with professors — critical skills that many new college students must learn on their own. In between, they got 80 minutes for lunch. Most used that time to study or meet with counselors.

You’re going to be stretched and pulled in ways you’ve never been before.

Reddick had never before been assigned so much work or held to such high standards. In math, he struggled to do basic computations without a calculator and to master topics he didn’t recall being taught in high school. In English, the online sources he cited in his papers were scrutinized, errors in his grammar and logic highlighted.

At home, he stayed up late working on a laptop the program loaned him. If it got too hot inside, he’d sit on the front stoop, accepting the clamor of traffic as the price of a cool breeze. A couple times, he broke down.

“He was burned out,” said Williams. “He was drowned.”

And he wasn’t alone. Many incoming EOF students are daunted — not only by the workload, but also by the holes in their learning that the summer program exposes. The instructors try to fill what gaps they can. But they also expect, even want, students to struggle in the summer when they’re surrounded by caring adults and peers from similar backgrounds. It’s a little like a failure vaccine that builds up students’ immunity through exposure.

As Reddick’s summer English instructor, Crystal Coble Hamai, put it: “Without the boot camp, if he had just come in in the fall and that was his experience in the first five weeks of school, then he might have said, ‘You know what, I don’t know if college is for me. I can’t do this.’”

‘It wasn’t going to be easy’

In early August, the Rutgers-Newark EOF students piled into two chartered buses. They wore nice clothes — dresses and button-down shirts, the occasional tie. Reddick had on a three-piece suit. Thirty minutes later, they disembarked at a Hilton hotel in Springfield township and entered the grand ballroom. They had come to celebrate the end of boot camp.

It was lunchtime, and the students filled their plates with heaps of cheesy pasta, baked chicken, and steamed vegetables. Then Dean Walker McCall addressed the students. She wore a headscarf around her long hair and a black blouse with sparkling embroidery.

“I cannot tell you how proud I am of each and every one of you,” she began. She admitted that she had worried about some of the students. But they had dug deep and pulled through.

“We told you it wasn’t going to be easy,” she said. “Did we lie?” The students roared back: “No!”

She reminded them that she had also promised they would form a new network of friends and allies, repeating her saying that EOF stands for “extension of family.” That prediction had also been borne out.

The students had bonded over their shared work and anxieties. They had let off steam during weekly social events at the campus athletic center, where they learned to dance bachata and played pick-up basketball alongside their instructors. And that was by design, a way to combat feelings of isolation and being adrift that can besiege first-year students — particularly poor students, who are more likely to live and work off campus.

Now, she told the students that, in just a few weeks, they would officially start as Rutgers freshmen. They were already intimately familiar with the campus, and had taken classes that mirrored ones they would take this fall. So while their number was small, just 109 students, they were poised to become campus leaders and guides for the non-EOF freshmen. “They’re going to be lost like you were at the beginning of the summer,” she explained.

Finally, she had them peer even further into the future. “I personally can’t wait until four years when we’re in, perhaps the Prudential Center, screaming and hollering and congratulating you on your graduation,” she said. As if rehearsing for that promised day, Reddick and the other students screamed and hollered and cheered.

The event celebrated students’ hard work during the summer regardless of how well they performed in class. But the next day, it was time for them to learn their final grades.

Reddick was sent to Dean Walker McCall’s office to receive his. He’d already gotten a preview in English. For the final, Reddick had written a five-page research paper titled, “The Miseducation of Our Urban Youth.” “Growing up in a metropolitan area, I attended public school, and I witness first hand some of the disparities that plague the urban area,” he wrote. He got back a C.

Now the dean informed him that, in addition to a C in English, he had earned an A in his study skills class. But he had ended geology with a D and math with an F, according to Reddick. (Walker McCall declined to discuss individual students’ grades.) His average was a D — not the C required to pass. He would not be admitted to Rutgers.

Stunned, Reddick handed over his student ID. He held back his tears during the meeting. But that night, he awoke at 3 a.m. and began to sob. “I failed, I failed, I failed,” he repeated to himself. And it wasn’t just himself he had betrayed. “I failed the world.”

The starting line

Statistically speaking, the deck had been stacked against Reddick all along, as it is with so many other aspiring college students like him.

Many low-income students of color attend segregated, underfunded K-12 schools that struggle to prepare them for higher education, then are funneled into colleges with the lowest graduation rates. Almost by design, many of those students fail to earn degrees. Yet when that happens, it isn’t the unfair system that takes the blame — it’s the students.

When Reddick got the awful verdict that day, at first he wondered if he had been mistaken for another student. He felt as if he had worked 10 times harder that summer than he ever had before. Now he was told that wasn’t enough.

Then he thought about his mother, his siblings, his former classmates and teachers at Central. He had promised them he would achieve great things at Rutgers, then use his education to uplift Newark, the hardscrabble city he cherishes.

“People are waiting to see what I’m going to bring to the table, how full the plate is going to be when they receive it,” he said. Now that dream had vanished, leaving him with a vast emptiness inside. “I have nothing now.”

The decision not to admit some students even after they endured such a demanding summer program certainly appears harsh. But it reflects a clear-eyed acceptance of the fact that some students leave high school far behind the college starting line. “You

can’t undo that or fix that in six weeks,” explained Walker McCall. Far worse than rejecting a student who truly is unprepared for college would be admitting him, she said.

“The last thing we want to see is someone come here, fail semester after semester, run out of funds, and end up having to pay off loans and debt that they are not financially equipped to do because they don’t have a degree that’s going to get them a good-paying job,” she explained.

People are waiting to see what I’m going to bring to the table.

Yet, with Reddick, Walker McCall ultimately decided that he actually did have what it takes to succeed at Rutgers — not just raw intelligence and ambition, but also a willingness to learn from his struggles. There had been some EOF students who failed to meet the summer program’s minimum requirements and did not seem to learn from the experience. The dean would not admit them. But Reddick had owned up to his shortcomings and drawn lessons from them.

“At the end of the day, he demonstrated growth in the six weeks and maturity and I think came to some realizations,” she said.

So a few days after her meeting with Reddick, Walker McCall asked him to return to her office along with his mother. After the dean spoke privately with Reddick’s mother, she shared the news with him: She was giving him a second chance. He would be allowed to start at Rutgers this fall, but on academic probation. There would be mandatory tutoring, a supplemental math class, a reduced course load — and higher stakes than ever. A GPA below 2.0 in his first semester could mean the end of the road at Rutgers.

“The God I serve is so good to me!” Reddick exclaimed after the meeting. He vowed to watch online math tutorials before classes began in a few weeks. He would skip campus parties that fall. He would earn all A’s.

At Rutgers-Newark and its EOF program, Reddick had found a university that saw the tough circumstances some students face not simply as obstacles to surmount; they were also wells of strength to be tapped. And, unlike at some institutions, its leaders said they would not leave students to sink or swim. Instead, they promised to do all in their power to steer students to graduation. “I’m clear that once they’re here, they’re our responsibility to get out,” said Sherri-Ann Butterfield, the executive vice chancellor.

Whether Reddick and the university would achieve their shared goal of getting him to graduation would only start to become clear in the months ahead. For now, all Reddick could do was commit completely to this fresh start.

“My goal is to knock this out with a straight A-plus,” he said that August afternoon. “To prove to myself that I am capable of passing. To prove to them that my word is my word and I am a person who really seeks a great future.”

This project was produced with support from the Education Writers Association Reporting Fellowship program.