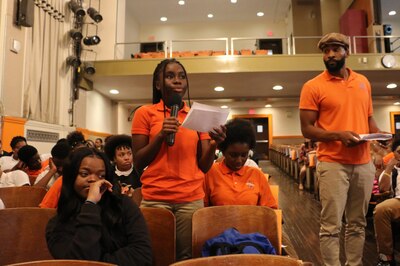

Cheers rang out inside Weequahic High School’s ornate auditorium Wednesday as one student after another performed original poems, skits, and dances responding to the brutality of American slavery and the racism used to justified it — along with the persistent fight for freedom by black Americans.

The students’ work was inspired by The 1619 Project, a collection of essays and poems in the New York Times Magazine about the enduring legacy of slavery and black resistance. Among the rapt audience members Wednesday were school board members, district officials, and Nikole Hannah-Jones, the award-winning journalist who spearheaded the Times project.

“I am so proud of you all,” Hannah-Jones told the students, who attend Weequahic and American History High School. “This is by far the best program that I have seen in response to this.”

She praised the students and their teachers for embracing the ethos of the project, which reframes U.S. history by arguing that the beginning of American slavery in 1619 was the country’s “true founding.” Random House Group imprints announced Wednesday that it will turn the project into a series of books for young people and adults.

“If you don’t think that your story is being told correctly,” Hannah-Jones said to the students, “then you tell it yourselves.”

Later, she announced a $1,000 donation to each school to pay for books on black history.

Shortly after the project was published in August, Newark district officials began adapting it for use in schools. They pulled from materials created by the Pulitzer Center to help bring the series into classrooms. And they developed questions to accompany the essays, which explore how the legacy of slavery and structural racism continue to shape politics, the economy, and health care in the U.S. 400 years after white colonists in America first bought enslaved Africans.

Newark now joins a handful of other districts — including Chicago; Washington, D.C.; and Buffalo, New York — that plan to teach lessons tied to the series in all their high schools, Hannah-Jones said. Brian Mooney, who works in the district’s office of teaching and learning, said Newark teachers and administrators will be invited to refine and expand the new teaching guide.

“We want them to help us build this out and continue for it to be a living, breathing document,” he said.

Newark’s adoption of the 1619 materials is part of a larger effort to reevaluate and revamp the curriculum used in schools. This spring, the district selected new English, math, social studies, and science textbooks, opting for those that celebrate the cultures of Newark’s students, who are mainly black and Hispanic.

Officials are also partnering with educators in neighboring Orange and experts at Rutgers University-Newark to develop teaching materials about the central role of black Americans in U.S history. New Jersey schools are mandated to teach that history under the state’s 2002 Amistad law, but many have called for more guidance and resources from the state.

“Amistad is written in the legislation,” Superintendent Roger León said earlier this year, “but if you try to find it in any of our curriculum, it is absent.”

The district provided Weequahic and American History with copies of the 1619 issue of the New York Times magazine and related teaching materials. Students studied sugar, which fueled slavery and is linked to disproportionately high rates of diabetes among black people today, and listened to classic Motown tracks while learning that so much American pop music originated with black people but was cribbed by whites.

Students then produced creative responses to the essays, which they performed Wednesday.

“Great America, great America, what would you be without African Americans’ forced labor and being sold for profit as if they were a product?” said Shakon Cumming, a senior at American History, reading from his piece on the origins of American capitalism.

Jada Jones and Daniela Brito, two juniors at American History, recited their poem that traces a line from slavery to mass incarceration.

“Once known as slaves, now as inmates; you have the right to remain silent,” they read. “Just because you’re black, you’re a criminal; and that’s your fate.”

Several Weequahic students performed scenes from the lives of Ida B. Wells, the crusading journalist and anti-lynching activist who was born into slavery, and Simeon Booker, a trailblazing black reporter who in 1955 covered the murder of 14-year-old Emmett Till and the acquittal of Till’s killers by an all-white jury.

Twins David and Daniel Ekhator, who played Booker and Till in the skit, and Foluso Adedeji, who narrated, said the project had helped them understand how the history of slavery and violence against black Americans remains all too relevant.

“We have to show other students here at our school that it’s not just something you read and forget about,” said Daniel. “You can still see the effects today,” added Adedeji.

Robert Hylton, a Weequahic English teacher who performed two of his own spoken-word poems, said that black people like him and his students often struggle with “where we belong and how we fit into America.”

“Just like myself, they didn’t see how important they were to America and that they contributed greatly to the democracy of America,” he said. But the project made clear: There would be no America without its black citizens, whom Hannah-Jones calls “the perfecters of democracy.”

Hannah-Jones told the students that it was in a black studies class in high school that she first learned the history that would decades later inspire The 1619 Project. She then read an excerpt from her 1619 essay, and students peppered her with questions. They asked about the role of immigrants and other marginalized groups in the struggle for justice, about conservative critiques of the project, and why she felt the project was necessary.

“From the moment we as black folks take our first breath, we are taught that we’re the problem,” she responded, even though history shows how white people in power created many of the conditions that black people face today. “When you have the facts, you can push back against the narrative that people want to write about you.”