The transformation of Barringer High School started long before Newark’s annual school fair kicked off at 10 a.m. on Saturday.

Blue and white balloons had been strung along the hallways. Flyers, candy, and branded pencils were piled atop booths in the gymnasium advertising the city’s elementary schools, while the high schools set up shop inside classrooms. And in the media center’s “winter wonderland,” Santa Claus pulled on his white beard and red cap ahead of a long day of festive photos.

By midmorning, hundreds of families — anxious middle-schoolers, squirming toddlers, and pamphlet-clutching parents — were streaming through the school. It was showtime.

“Welcome! Come on inside,” Naseed Gifted, the principal of Malcolm X Shabazz High School, told a parent passing by the school’s assigned classroom. “Check it out. We’ve got a whole bunch of new things that we’re offering.”

Each December, Newark families begin applying to schools for the coming year. They can use the city’s universal enrollment system to apply to any district-run school and participating charter schools, or apply separately to other charters and county-run schools.

The enrollment fair, which the district hosts, brings that school-choice process to life as schools market their unique offerings and families explore their many options. Every traditional and charter school that participates in the universal enrollment system, which had its new online platform launch on Saturday, is represented at the event.

The fair is especially high stakes for high schools, which, unlike many elementary schools, cannot count on students to enroll simply because they live nearby. Instead, they must convince discerning families that their particular blend of academics, school culture, and extracurricular activities will launch students into the colleges or careers of their dreams.

That sales pitch can pose challenges for comprehensive high schools such as Shabazz and Barringer. Unlike the district-run magnet schools and the county-run vocational high schools, the comprehensive schools do not screen applicants; instead, they admit any student they have space for. As a result, the schools enroll many students who struggle academically or arrive in the city midyear, sometimes from other countries where they spoke little or no English. When measured by their test scores, attendance, graduation rates, and college enrollment, the comprehensive schools tend to trail far behind the selective magnet schools.

Newark’s new superintendent, Roger León, has promised to change that by ramping up the academic rigor at the comprehensive high schools. In recent weeks, the district has also rolled out new vocational “academies” inside the comprehensive schools designed to prepare students for careers and to help with recruitment.

On Saturday, the schools were eager to tout the new programs.

In one classroom that has been converted into a model courtroom, students in police uniforms stood guard in front of a judge’s bench waiting to tell visitors about Barringer’s new law and public safety academy, which launched this fall. Next door, a DJ provided the soundtrack as a student explained how his carpentry class built the judge’s bench and his criminal-law class held a mock trial with SpongeBob SquarePants as the defendant.

Barringer’s new principal, Jose Aviles, has ambitious plans to expand the academy so students can eventually specialize in specific legal fields such as education and immigration. His hope is that students who decide not to enter college right after graduation will be able to find jobs as paralegals, police aides, security guards, and computer technicians trained in cybersecurity.

The ultimate goal, he said, is that Barringer and its new academy — also called a career and technical education, or CTE, program — emerges as a top choice in Newark’s crowded field of high schools.

“We don’t want to be satisfied with the status quo,” said Aviles, who returned to Barringer this year after helming the school nearly a decade ago. “We want each year to get better and better to the point that our CTE program is so robust that we can compete with the magnet schools.”

Yet the new vocational program won’t be enough to convince some skeptical families that the school has turned a corner. So Aviles also highlighted other recent improvements.

Attendance is inching up, suspensions are trending down, and all but two of 17 teaching positions that were vacant at the start of the school year have been filled through aggressive hiring and paying some teachers to take on extra classes, he said. The school’s parent association has been rebooted and nearly 500 parents and guardians attended the most recent parent-teacher conference — a dramatic increase from years ago, when Aviles recalls a couple dozen parents showing up on report-card day.

“Barringer’s had a pretty rough reputation over the years,” Aviles said. “It’s going to take us some time to break that reputation. But I think we’re doing it.”

Last year, the district’s highest-performing magnet schools — Technology and Science Park — topped the list of high schools that rising ninth-graders most often ranked first on their enrollment applications, according to district data. Barringer did not make the top 12.

That disparity in demand was on full display Saturday. While parents and students trickled into Barringer’s rooms, they flocked to presentations by Technology and Science Park that attracted standing-room-only crowds.

Julie Hinds was one of the parents. She had scrutinized the high schools’ state progress reports, their academic offerings, and data on how well they prepare students for college. Based on her research and the schools’ reputations, she decided that her eighth-grade daughter at Elliott Street Elementary School would be best-served by a magnet or charter high school — even though the family lives just five minutes from Barringer.

“Unfortunately, it’s not an option for me,” she said.

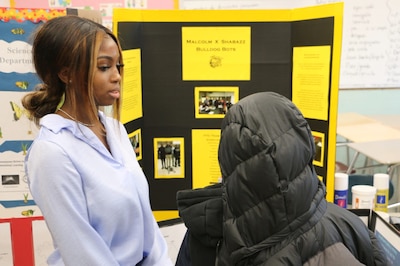

In a different classroom Saturday, Shabazz senior Cerryann Jeune was trying to show visitors that there is much more to the comprehensive schools than what they might have heard.

Like Barringer, Shabazz boasts a wide array of extracurriculars — from robotics and chess clubs to bowling, cheerleading, football, and many other sports. It allows students to earn college credits through partnerships with the New Jersey Institute of Technology and Rutgers University. And it is launching a biomedical engineering academy this fall as another option in addition to the school’s existing video game and app-development academy and its natural health and beauty science academy, where students can train to become licensed cosmetologists.

Jeune, who hopes to study biology at Howard University, developed her own hair-care products in Shabazz’s beauty science program. And she’s eager to learn about 3D printing in the engineering academy.

“Not a lot of people know about the great things that are going on at Shabazz,” she said. “All they hear about is the negativity.”

Her classmate, Quan’Yè White agreed. A member of the Malcolm X Shabazz Pride Team, which is committed to improving and promoting the school, White said that reputations take time to revise.

“Perceptions are hard things to change,” she said. “What we’re doing right now is putting in the work to change people’s minds.”