A few weeks ago I sat in the library at Christopher Columbus High School and listened to a Department of Education official explain to our confused and upset parents that closing our school would actually benefit their children. The official argued that the school’s closure would actually increase students’ chances of graduating, rather than damage them.

This seemed a counterintuitive idea to me, so I decided to dig into the data. The DOE keeps a wonderful public archive of graduation and dropout data in longitudinal reports. I looked at what happened to students at Bronx high schools Roosevelt and Taft during the years they phased out, and compared them to Columbus and John F. Kennedy along with city averages.

Why did I focus on these schools? I began my career as an English as a Second Language for seven years at Kennedy. In 1999 I was invited to become a staff development specialist for the DOE’s Office of Bilingual Education (later the Office of English Language Learners) and for two years I visited Roosevelt every Tuesday and Taft every Wednesday to support their bilingual and ESL teachers. Then in 2002 I moved to Columbus, where I’ve worked as teacher and UFT Teacher Center staff. Looking at these four schools provided me a glimpse into the sad unraveling of the places I spent my career.

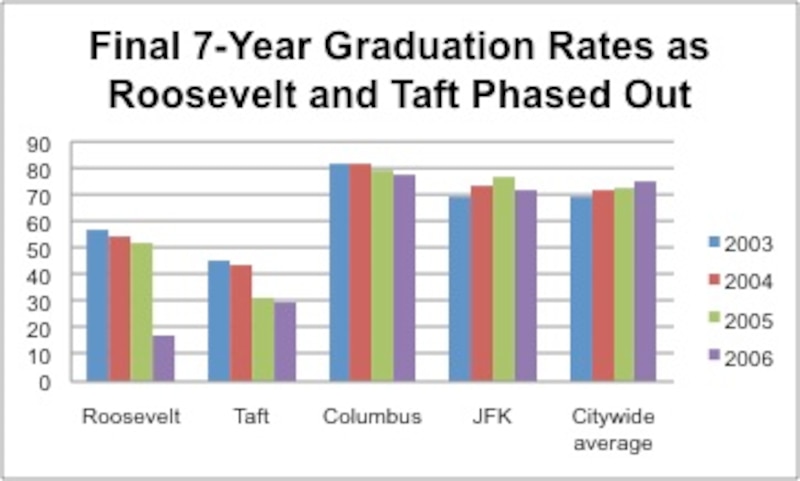

First, I took a look at the 7-year longitudinal studies — those showing the ultimate outcomes for students who entered Taft and Roosevelt in the last four years the schools admitted students. In both cases, graduation declined for the first couple of years by a small amount, with the final two cohorts doing significantly worse. Roosevelt graduated only 17.6 percent of the students who entered in 2002, and Taft graduated just 29.5 percent of them. These outcomes did not compare favorably with either the citywide average for those years, or schools currently on the chopping block, Columbus and Kennedy.

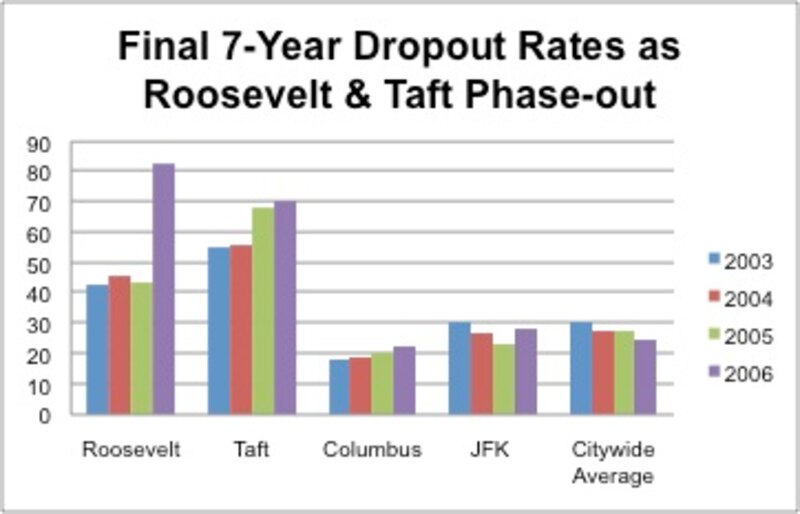

Conversely, I took a look at dropout rates for the same cohorts. Here we see rates in the closing schools rising to the point where, in the final cohort, over 80 percent of the final cohort at Roosevelt dropped out, and over 70 percent of the final cohort at Taft.

All of the schools also discharged a large number of students during these years. Students who leave their schools for GED programs are classified as discharged, but advocates also believe that many discharged students would be more accurately counted as dropouts. Taking into account discharges, Roosevelt graduated only 9 percent of its final cohort in seven years.

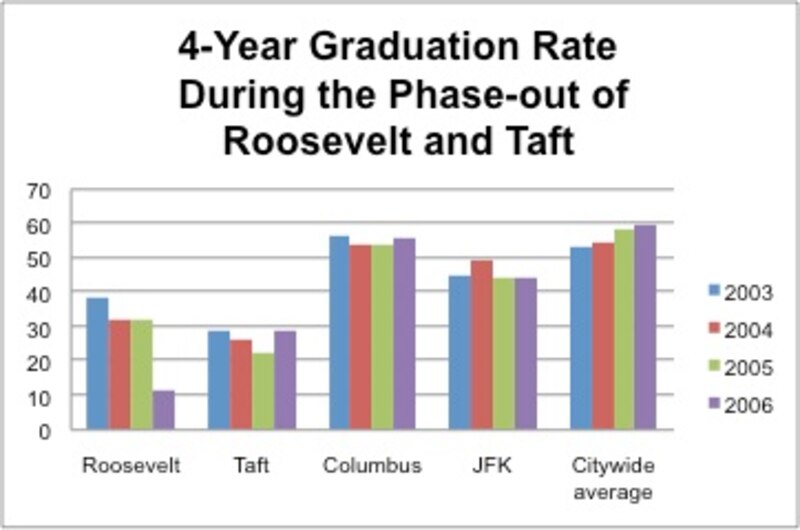

I hypothesized that there would be a significant difference between the closing schools and non-closing schools when I looked at the initial 4-year graduation and dropout rates against the final 7-year rates, since Columbus and Kennedy would have had the additional time (an extra three years) to work with high-needs students, including those who speak little English, to help them to graduate. (The city’s own longitudinal data reports point out that a high percentage of English language learners graduate in the three years after their original graduation date. ) The closing of Taft and Roosevelt would leave the educators in those schools just four years with each child, regardless of their need level, for the final class of students.

The 4-year graduation rates, particularly in the first years, did not show the same dramatic difference. The final graduating class from Roosevelt however, was a mere 11.6 percent.

But then I looked at the 4-year dropout rate. This was simply stunning and left me feeling very queasy. The percentage of students dropping out rose dramatically over the four phase-out years — with the 4-year dropout rate at Taft topping 70 percent and Roosevelt at 63 percent in their final year of existence!

So now for the mystery. Why does the DOE claim that students benefit during the closure of our schools? Yes, I only focused on two local Bronx schools, but glances at other schools that have been closed suggest similar patterns.

The department usually focuses on the argument that as schools shrink they are able to provide a greater degree of personalization. If this is the case, what happened to produce these devastating outcomes for students at these schools? Could it be that many teachers whom students had looked to as mentors left or were excessed in the process of phasing-out? Could it be that as time passed there were fewer opportunities to engage in the extra-curricular and senior activities that inspire so many students? Could it be the loss of libraries and other school facilities that were closed as the years?

Maybe the department needs more time to consider the increasing concentrations of poverty and academic need in certain high schools. There is indeed a domino effect of school closures: Larger high schools that stay open see their highest-needs populations rise as other schools close around them.

Last week’s release of a 2008 DOE internal report by the Parthenon Group would appear to confirm that the department has known for several years that the concentrations of high-needs students at some schools virtually destined them to failure as centralized admissions offices continued to fill those schools with ever-increasing proportions of such students. The report released last week by the city’s Independent Budget Office also suggests that schools currently under threat of closure have higher concentrations of need than their peers — including a considerably higher percentage of families identified as low-income (particularly at the high school level) — a factor the Parthenon report does not even consider. This is significant when we consider that socioeconomic status is a great predictor of ultimate academic attainment.

As a concerned educator in one of the schools facing an uncertain future, I believe that it would be wise, all things considered, to postpone the decision on our schools until these various reports can be given full consideration. Maybe the key fix our schools need is a more balanced admissions practice.

About our First Person series:

First Person is where Chalkbeat features personal essays by educators, students, parents, and others trying to improve public education. Read our submission guidelines here.