Avram Barlowe posed a provocative question during a class in December. “Are people taking this seriously?” he asked his Urban Academy students. “Scrubbing toilets is the same as giving away organs?”

Barlowe’s question wasn’t a non sequitur. His co-teacher, Adam Grumbach, had just argued that people should be allowed to sell their organs because other kinds of uncomfortable or dangerous work, like cleaning or digging the Second Avenue subway, are legal. Barlowe was looking to get students riled up so they’d join the debate.

It worked. Soon, the students were beginning the process of developing arguments and using evidence to back them up — two skills emphasized by the Common Core standards now in place in New York. Though Urban Academy students are exempt from most state exams, the popular transfer school in Manhattan has been teaching those skills for nearly two decades through a class called “Looking for an Argument?”

The course is now taught in at least four city schools, and its emphasis on reading nonfiction texts and writing argumentative essays could make it a useful tool for teachers looking to align their classrooms with the new standards.

At the same time, the course’s emphasis on personal opinion stands in contrast to Common Core architect David Coleman’s singular focus on students’ ability to analyze the “author’s choices.” Looking for an Argument only works if students say what they believe.

Maintaining momentum

The course operates as a series of “cycles,” beginning with students watching teachers debate for about eight minutes. Then they jump in with their own questions and opinions.

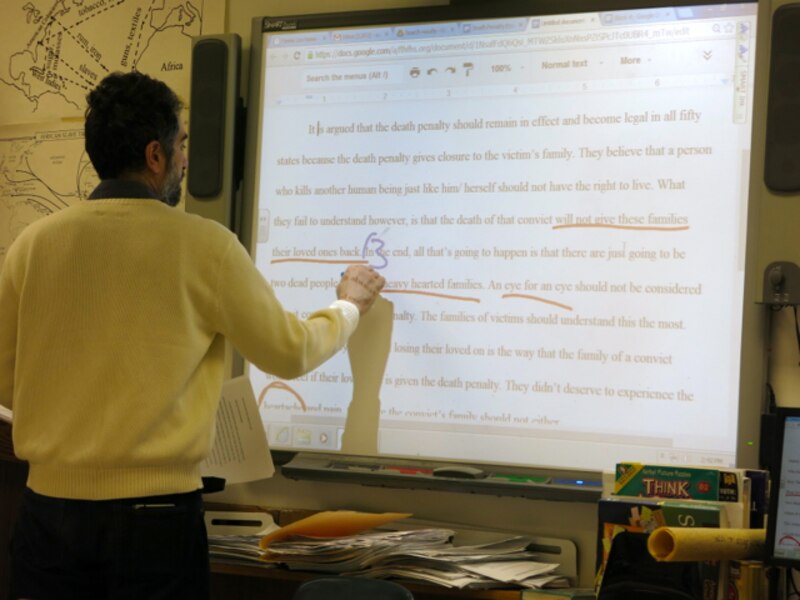

Over the next week or two, they read news articles about the topic, take notes, debate more, and write an argumentative essay. Then they repeat the cycle with a new theme, such as the death penalty or the relationship between luxury items and happiness.

The course’s structure asks teachers to make a bet: that it’s worth having students move on to the next cycle, rather than revise their essays, in order to build momentum and help students see the connections between each stage of the cycle.

“Writing is about organizing and explaining the way you think,” Barlowe said. In his eyes, if teachers devote too much class time to perfecting students’ essays before moving on to the next topic, they risk losing the link between thinking, speaking, and writing that he sees as the course’s core.

At Urban Academy, this approach makes for fresh, provocative, and, at times, unwieldy initial arguments and essays.

During the organ debate, after Barlowe tried to discredit the comparison Grumbach drew between doing a dangerous job and giving up an organ, Khadim Seck, a sophomore who hadn’t spoken yet, raised his hand. “People will do anything for money,” he said, returning to a point Grumbach made earlier in the debate about the futility of regulation. “It doesn’t matter whether or not it’s allowed, people will do it either way.”

After the initial argument, students spend the rest of each cycle developing an informed argument and providing evidence to support it. During most cycles, students also critique each others’ highlighting or note-taking strategies, critique their own essays, and receive feedback from their teachers.

Adapting the course

As a member of the New York Performance Standards Consortium, Urban Academy has more leeway to experiment with instruction than most schools, because its students prepare portfolios instead of taking most Regents exams. But Barlowe believes Looking for an Argument can be a powerful tool regardless of whether teachers are preparing students for tests or portfolio projects.

The course does take time to master. Barlowe said it took several years to develop the ability to sense when to linger on a topic or skill and the flexibility to know when to move on. That’s why, in 2002, he and his colleagues began running trainings through the consortium open to any educators interested in teaching the course.

According to Ann Cook, executive director of the consortium and a founder of Urban Academy, the consortium has run at least 50 workshops focused on Looking for an Argument, and hundreds of teachers have observed the course at Urban.

Barlowe said he’d like to see the Department of Education invest in more training, particularly as teachers across the city scramble to adapt their teaching to the Common Core.

“If the Department was truly committed to doing some of this stuff, we could do staff development over the summer,” he said. Additional funding could also allow Barlowe and his colleagues to spend more time more time observing the class at other schools and helping teachers adapt the class to their students’ needs.

Claire Cox, an English teacher who taught the course at Brooklyn’s Gotham Professional Arts Academy during the school’s first year in 2007, said she and her colleagues adapted the curriculum to provide more class time for writing, revising, and instruction on specific writing skills her students needed.

“We used the same structure and stretched it out,” she said. “You can prioritize what you want.”

“How people actually think”

At Fanny Lou Hamer Freedom High School in the Bronx, students also take a stretched-out version of the course. Co-teachers Aaron Broudo and Mike Centrone have built in more time for students to write and revise their essays in class. But they haven’t given up Looking for an Argument’s emphasis on students’ opinions, which they said has been essential to keeping students engaged in the class and especially in the writing process.

Broudo pointed to Joshwell Caban, a junior, for whom the structure of Looking for an Argument worked particularly well. Caban speaks Spanish at home and rarely said more than two sentences at a time when the class began.

“I wasn’t used to it, to arguing with someone else about one topic,” Caban said. But over the course of the first few cycles of arguments, he got caught up in the arguments and began talking and writing more.

Midway through the semester, when Broudo and Cestone replaced their usual opening arguments with panels of four students who argued with each other before the rest of the class joined in, Caban begged to be on the first one.

Caban’s writing, though much improved, is far from perfect. He’s still figuring out how best to connect his evidence to the arguments he’s trying to make. But he argued passionately against the death penalty during the panel, and though his claims weren’t airtight, he cited the costs of execution and other countries’ stances on the death penalty and explained how that information supported his point of view.

Principal Nancy Mann, who watched most of the debate, wasn’t surprised to see a quiet student start speaking and writing during Looking for an Argument.

“Human beings have ideas, express them, rewrite them, have new ideas,” she said. “That’s how people actually think.”

Want the latest in New York City education news? Follow Chalkbeat on Facebook or @ChalkbeatNY on Twitter.