In his first six months in office, Mayor Bill de Blasio has had a nearly singular focus on providing needy students with expanded education services. But thousands fewer struggling students will be attending summer school this year after city officials changed the way students qualify for the program.

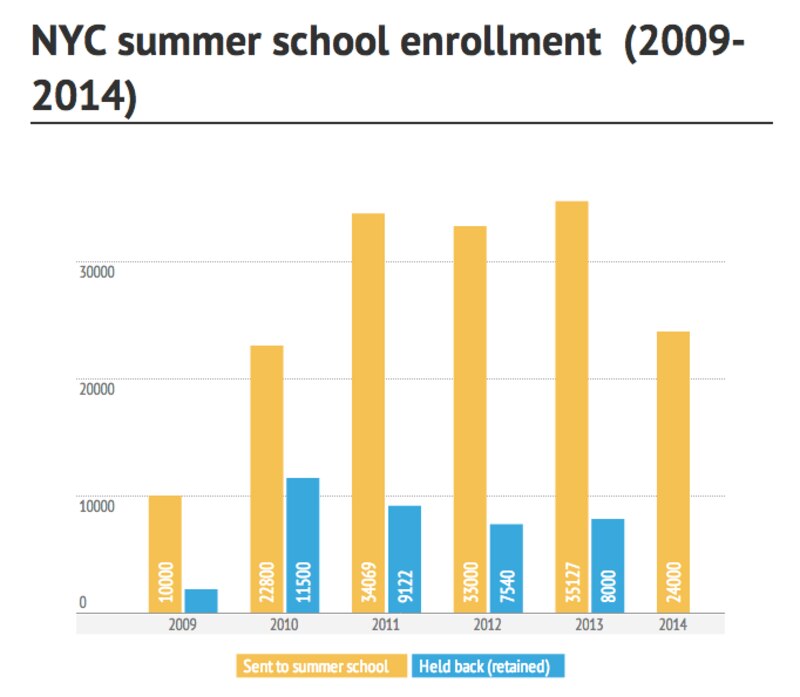

Principals sent about 24,000 third- through eighth-grade general education students to summer school this year, down from 32,205 students last year. The 25 percent drop puts summer school enrollment at its lowest level in four years, even though nearly three of four students scored below proficient in both reading and math on state tests last year.

The steep decline comes less than three months after officials announced they were changing grade promotion standards put in place by the Bloomberg administration during a decade-long push to ban “social promotion.” The new policy, buttressed by a state law passed earlier this year, bans the use of state test scores as a major factor in promotion decisions—including summer school recommendations. It also gives principals more discretion when choosing which students have to attend summer school.

Though the process changed, officials insisted in April that the outcome — summer school enrollment — wouldn’t. But this year just 7.4 percent of all general education students were sent to summer school, compared to 10 percent last year.

The summer school drop is a rare case of students losing services because of policies pushed by the de Blasio administration. The city will spend an extra $445 million this year for new or expanded after-school and prekindergarten programs that will affect more than 40,000 students.

City officials downplayed the numbers and didn’t explain why enrollment was lower than expected for the program, which began Tuesday and lasts until the end of July.

Chancellor Carmen Fariña called last year’s numbers an “anomaly” this week, though the 2013 numbers are consistent with the previous two years. (In 2011 and 2012, like last year, the city sent about 10 percent of students to summer school based on preliminary test score data. For those two years, though, a smaller percentage actually scored low enough under the old policy to technically warrant the extra help—a fact that only emerged when official test scores were released in August.)

Aaron Pallas, a professor of education at Teachers College who is a proponent of the new policy, said this year’s drop could be a result of principals being given poor guidance by the department or not following directions, but that it was impossible to know without additional information.

“It does seem to warrant further investigation,” Pallas said.

Educators have mixed feelings about summer school’s ability to tackle the city’s achievement gap. The program has consisted of little more than English and math tutoring designed to help students pass an end-of-summer test so they could advance to the next grade, many said.

“If summer school as it is presently designed were effective, we wouldn’t have so many kids entering high school who can barely read,” NYU Professor Pedro Noguera said.

John Galvin, an assistant principal at a school in Brooklyn, said the program’s singular focus made for a “dreary summer” for both students and teachers.

“This created an environment that led to disenchanted kids and made it tougher on teachers to do their jobs,” Galvin said.

But summer school now has the potential to become more engaging, Galvin said, since students no longer need to pass a test to be promoted in August. That test was eliminated under the new policy and replaced with a principal’s review of a portfolio of student work.

Advocates say that NYC Summer Quest, a full-day program that combines tutoring with field trips and other camp-style activities, is a better intervention for low-income students. Summer Quest added 1,000 seats this year and will serve a total of 2,800 students.

Still, education officials have insisted that summer school is better than nothing, especially for poor students who make up the majority of summer school attendees and who are more likely to lose ground to their middle-class peers over the summer months. The program, which cost the city $22 million last year, has structure and small class sizes, two factors that researchers believed contributed to a 2009 study’s findings that summer school had “small, positive effects” on student learning.

“If we had our way, even more students would benefit from extended learning and additional time in summer school,” former Chancellor Dennis Walcott said in 2011, when a higher-than-expected number of students were recommended for summer school.

Sign up for Chalkbeat’s morning newsletter here.