From the moment they met him, the staff at School of the Future were concerned about Joseph.

The incoming sixth-grader had attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, another behavioral disorder, and a learning disability, which became apparent last year when they interviewed him and reviewed his academic records.

The educators at the public school in Gramercy Park are known for their prowess at integrating students with disabilities into general-education classes, and at first they tried that approach with Joseph. They placed him in a mixed class with typical and disabled students headed by two teachers, gave him modified assignments, sent him to small-group reading sessions, and dispatched a seasoned special educator to work with him.

None of it was enough.

Joseph still read at a third-grade level and acted out, sometimes lying on the classroom floor or picking paint chips off the wall while teachers tried in vain to get his attention. He rarely completed assignments and often skipped school.

Finally, the staff decided that Joseph belonged in a class just for students with disabilities. But the small School of the Future has too few students who require a special-education-only class to justify creating one.

In the past, it would have been easy enough to send Joseph to a middle school with the class he required. But since the city instituted a new set of special-education policies, every school is now expected to meet the needs of all but the most severely disabled students.

Still, a school can’t offer what it doesn’t have.

So beginning in November, Joseph’s parents, an advocate, school-support network officials, and School of the Future staff began lobbying the education department to move Joseph to a school with the class he needed. By the time city officials had combed through the school’s finances and class offerings to determine if it could meet Joseph’s needs, then approved a transfer when it decided the school could not, the school year was almost over.

“The school was very supportive, but its hands were tied,” said Joseph’s mother, Clara, who asked that her last name be withheld because she works for the education department.

Department officials said such transfers are uncommon and rarely take so long to authorize. But while Joseph was waiting for the right school, Clara said, “the child was suffering.”

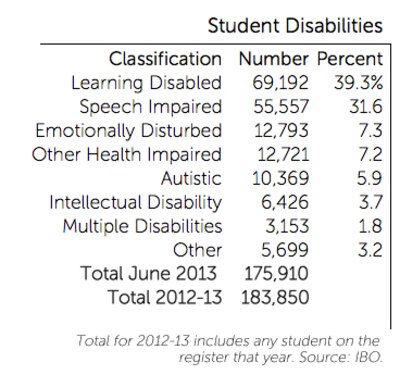

Over the past four years, the city has overhauled the way it educates nearly one-fifth of its public school students – those with disabilities – a group so large it outnumbers the entire Dallas school district.

No longer are special-needs students to be bused to distant schools to get the services they need or tucked away in forgotten rooms, the city decided. Instead, most are now expected to enroll at the same schools and learn the same material as their non-disabled peers, and take classes alongside them whenever possible.

Parents and teachers who have watched students languish in special-education classrooms have embraced the city’s new drive toward inclusion, which is backed by research and federal law. The shift honors the potential of students with disabilities and asks every school to play a part in helping them achieve it, proponents say.

But there is little data available about how the new policies have impacted students, even as some critics question whether they are always in students’ best interests. Meanwhile, interviews with more than two-dozen parents, students, educators, and advocates show that the changes have not come easily, with schools scrambling to carry out the new directives, while some students, like Joseph, are left stranded in mid-reform limbo.

“I really believe in the reform and the philosophy behind it,” said Stacy Goldstein, School of the Future’s principal. Still, she added, Joseph’s struggle “is a really good example of cases where students have fallen through the cracks.”

A move toward inclusion

To Britt Sady, the city’s push for inclusion makes perfect sense.

She has seen the research showing that the more time students with disabilities spend in general-education classrooms, the less often they miss school or act out in class, the higher their test scores, and the better their job prospects.

And yet, integration has hardly been the norm in New York’s public schools. As recently as 2011, students with disabilities across the state spent more school time isolated from their non-disabled peers than in any other state, according to one analysis.

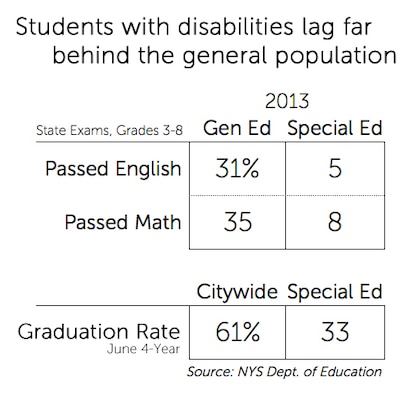

Whatever the cause, students with disabilities lag far behind other children in school. They have graduated at less than half the rate of their non-disabled peers for the past decade, with the gulf at times nearing 40 percentage points. Last year, just over 5 percent of the city’s special-needs students passed the state English exams, compared to over 31 percent of general-education students.

So when Sady met with the local school personnel who would decide the right kindergarten class for her son Noah, who has Down syndrome, she requested an integrated class.

Noah’s preschool class had just eight students, all with disabilities, so Sady knew a mixed-ability kindergarten class with many more students would not be easy for him. But that was part of the allure. Anticipating the higher expectations of an integrated classroom, she had already started to set higher standards at home (no more skipping the broccoli) and trained him to use a toilet rather than a diaper.

Meanwhile, educators at the public school Sady requested, Castle Bridge in Washington Heights, prepared for the possibility of serving their first student with Down syndrome. They visited other schools that serve such students and invited Noah to sit in on classes.

With the blessing of Castle Bridge’s principal, Julie Zuckerman, the placement team agreed to put Noah in the integrated classroom this fall – an outcome that has become much more likely since the start of the reform.

“I just wept with happiness,” Sady said. “It was another day I didn’t have to give up my dreams for my son.”

Former Mayor Michael Bloomberg first proposed a new approach to special education in 2003 – “We will no longer tolerate a largely segregated and largely failing system,” he said then – but it took until 2010 to pilot the new inclusion policies in 260 schools. Following a one-year delay, they were rolled out citywide in 2012.

The premise of the overhaul is that the school experience of students with disabilities shouldn’t be so different from everyone else’s and, in some ways, the system is headed in that direction.

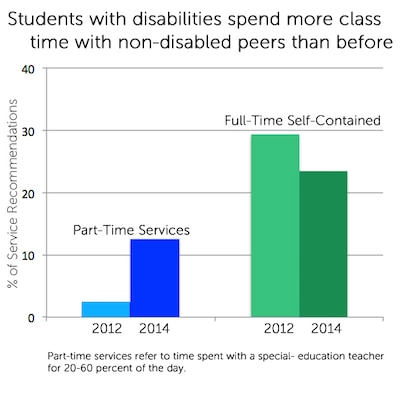

The share of students sent to full-time classes just for students with disabilities has declined by 6 percentage points over the past two years, according to data released by the city. Meanwhile, the share of special-needs students recommended to receive only part-time support has spiked by 10 percentage points.

Students with disabilities who are entering kindergarten, sixth, or ninth-grade can now enroll at the same schools as other students in their neighborhoods, rather than the nearest school with the right services.

Corinne Rello-Anselmi, the deputy chancellor who oversees the education department’s special-education division, said the new policies are beginning to take hold.

“Students now have access to schools they never had access to before,” she said.

Grappling with a new approach

The first year of the reform, Margaret found a kindergarten spot for her autistic son at the public school two blocks from their home on Staten Island.

Schools like the one in Margaret’s neighborhood, which might have served few special-needs before the reform, now have been told to take in almost every student who walks through their doors. But from the start, it has been unclear whether they have the expertise and staff to pull that off.

Margaret’s school never seemed to have enough of what her son needed. His full-time paraprofessional also had to assist other students, Margaret recalled. He could only see a speech therapist three times a week, even though his neurologist had prescribed daily sessions.

The following year, she asked for an integrated class for her son, but was told it was full. Only after she alerted department officials did the school find her son a space, according to Margaret, who asked that only her middle name be used since her son still attends the school.

“Let us open the door to your kid,” Margaret said, describing the school’s response to the reform, “but then we don’t know what to do with him.”

Since enacting the new policies, the city has provided training to thousands of educators. It also adjusted the way school budgets are set – giving schools more money for students in integrated classrooms than those in self-contained classes and increasing the rate for part-time services – as a way to encourage and fund the shifts.

Schools have also been urged to mix and match services for students. So, for example, a student now might take English in a class with all special-needs students, math in a mixed-ability class, and history in a general-education class but using materials prepared by a special-education teacher.

But even with those changes, many educators say they are still unable to adhere strictly to each special-needs student’s personal learning plan, known as an IEP. Instead, schools sometimes adjust the IEPs to match the services they can actually offer, according to parents, advocates, and educators.

At one small Brooklyn high school, there are too few students who require self-contained classes to afford them, according to a teacher there. So if a student’s IEP calls for such a class, the school gets the parents’ permission to amend the IEP to recommend integrated classes and extra supports instead, the teacher said. That was the case last year for four students with “extreme learning delays,” according to the teacher.

“They would definitely be in a self-contained class if that was offered,” she said.

Other times, schools may simply fail to offer the services prescribed by an IEP.

Olga Vazquez, a family advocate at ICL, a human-service agency, said concerned school guidance counselors sometimes call to report that students are not receiving IEP-mandated services. Recently, she informed a woman in Brownsville, Brooklyn that her son’s plan calls for regular occupational-therapy sessions, and yet his school had not hired such a therapist.

“Sometimes, if the parent doesn’t question it,” Vazquez said, “it just goes under the radar.”

Troubles with inclusion

As the reform steers students out of special-education-only classes, they are most commonly sent to classrooms that have two teachers and a mix of students with and without disabilities.

At P.S. 112 in East Harlem, those classes are so popular that the parents of non-disabled children often request them. The school is among a select few across the city where high-functioning students with autism are placed in integrated classes alongside their typical peers, through a program called ASD Nest.

The autistic students benefit from watching their peers’ social habits, while the autistic students often have expertise on pet topics to share, according to teachers. All the students learn to use yoga and meditation to control their behavior, and each child has access to an individual iPad.

To pull it all off, the co-teachers attend trainings together and meet weekly with other staffers to discuss each student’s progress – a strategy they have perfected after nearly a decade of participating in the NEST program. They also make use of the specialized training and small class sizes provided by the program, and the extra funding that comes with the school’s high number of special-needs students.

“Schools need to be trained and given the resources to do this,” said principal Eileen Reiter. “We’re just very fortunate that we can meet the kids’ needs here.”

Most integrated classes do not look like the ones at P.S. 112, which is one of only about 30 schools across the city with integrated co-teaching, or ICT, classes geared specifically for students with autism. Instead, most mix students with a variety of special needs with non-disabled children.

As the reform kicked off, many schools’ “kneejerk reaction” (as an education department official recently put it) was to place more students in the integrated classes as a way to promote inclusion while giving special-needs students the support of an extra teacher.

“People think that having two teachers is something magic,” said Dan Lupkin, a teacher at P.S. 58 in Carroll Gardens, Brooklyn who taught integrated classes for several years. But in reality, such classes are not right for every student, he said.

Integrated classes can be large and bustling and ill suited for students who are easily distracted or have trouble working independently, Lupkin and others note. Christon Solomon, a sixth-grade student with a learning disability who attended P.S. 276 in Brooklyn, said he could concentrate better and he received more attention during small-group sessions with other special-education students than in his integrated class.

“When I’m in my regular class,” he said, “sometimes they don’t notice me.”

The value of integrated classes can also be lost when too many students with disabilities are placed in them, overwhelming the teachers and depriving those students of non-disabled classmates who might serve as models or mentors. The city does not allow more than 40 percent of the students in an inclusion class to have IEPs, but teachers say that space- and staff-starved administrators sometimes find ways around the rules.

At a large elementary school in the Bronx in 2011, for instance, 23 out of 28 students in one integrated class had disabilities, or 82 percent of the class, according to the co-teachers. The situation drove one of the teachers out of the school. The following year, fewer students in the class had IEPs, but more than 40 percent still did, according to the teacher who remained. Last year, that teacher requested a general-education position because the integrated class had become too burdensome, she said.

“If it’s not implemented properly,” the teacher said, “merely moving [special-needs students] from self-contained to inclusion isn’t going to work.”

Department officials note that teachers can anonymously report such out-of-compliance situations. Teachers-union officials say the city responds promptly to such reports, but add that the fear of retaliation keeps some teachers and parents silent.

Even at the right enrollment levels, co-taught integrated classes are hard to run. The teacher-pairs must be well matched and well trained and have plenty of time to plan together, educators say. It is rare for all of those conditions to be in place, they add.

In a series of reports on the special-education reform commissioned by then-Public Advocate Bill de Blasio, the consultancy Perry and Associates found after hundreds of interviews with educators “an overwhelming request for more professional development.”

“The two things we heard repeatedly from schools,” said George Perry, Jr., the group’s executive director, “is that they want to make this work, but they need help.”

Looking for results

The city’s special-education system today looks very different from how it did a few years ago, with special-needs students attending schools and classes they wouldn’t have before.

Those changes suggest that the city’s directives and the new budget formula had their desired effect: Students with disabilities have become less isolated. But the reform isn’t meant to simply move special-needs students around − it’s also supposed to help them perform better in school and eventually graduate.

The record on that front is mixed.

For instance, the city found that state test scores inched up slightly more from 2011 to 2012 at schools that piloted the new policies than at comparison schools. But in 2013, both sets of schools did the same on the state English exams (though the pilot schools did better in math), according to the Perry report. An analysis by the city teachers union found that the test scores of students with disabilities improved less from 2010 to 2012 at the pilot schools than they did citywide. Meanwhile, the share of suspensions that go to students with disabilities has actually increased since the reform started.

Department officials insist that it is too soon to expect clear results from the reform, which is a long-term endeavor. Still, they say the new student placements mark a major development.

As the overhaul continues, the department is responding to educators’ concerns, the officials added. For example, it plans to set up more specialized programs at schools, like the one for autistic students at P.S. 112 and others for students with disabilities who are not native English speakers. It is also beefing up supports for struggling readers and training teachers to better manage student behavior.

But Chancellor Carmen Fariña does not appear poised to make any major changes to the new policies.

“The new chancellor is putting out the message to all schools that she strongly believes in an inclusive environment,” said Rello-Anselmi, the deputy chancellor.

That bodes well for Stacey Saunders and her son Thomas – though, for him and most special-needs students, inclusion alone won’t be enough to set him on the path to graduation.

After a rough kindergarten year, where Thomas spent some 45 days in suspension, Saunders moved him to a different school near their apartment in Harlem.

The new school also had trouble serving Thomas, who has been diagnosed with an emotional disturbance. Teachers in Thomas’ special-education classroom rarely used the strategies outlined in his behavior plan, Saunders said, and she had to send him to a private clinic to get the counseling services she had requested from the school.

But, in line with the reform, the school has also tried to shepherd Thomas into general-education classes. After he kept up with the work in an integrated math class, he was soon nudged into integrated science and reading classes.

Suddenly, Thomas saw that he was doing well in school and his self-esteem improved. This fall, he will split his time between integrated and general-education classrooms.

“He’s made a lot of progress – a lot, a lot, a lot,” Saunders said. “Now, I just need to make sure he keeps getting the services he needs.”