When students at the East Side Community School were trained Tuesday on how to behave during police stops, many found the information all too handy.

During one session at the combined middle and high school, 11th-grade students asked a trainer from the New York Civil Liberties Union whether officers are allowed to keep asking you questions after you decline to answer, rifle through your wallet, or stop you from recording an arrest. They wanted to know, they said, because they or their friends had been in those situations.

“It’s like getting bullied, in a way,” explained Joshua Almonte, 16, who said he was recently confronted and questioned by an officer while buying snacks in a bodega during a school lunch break. “When you know your rights, you feel more protected.”

The school-wide trainings come after students spent their first few weeks of history class this year studying the recent events in Ferguson, Missouri, where an unarmed black teenager was fatally shot by a white police officer. The events there resonated with many students — and not just because a black Staten Island man died after an encounter with police just weeks before the Ferguson shooting. Even at this selective school in Manhattan’s East Village that boasts above-average test scores and a diverse student body, many students say they view police stops as a fact of life.

“It’s something we’re constantly dealing with as a community,” said longtime Principal Mark Federman, who himself was arrested in the school several years ago when he tried to intervene as school safety officers arrested a student.

Since then, the school has not had similar problems with its safety agents and, in general, discipline is not a major concern, Federman said. That contrasts with some other schools where students are often suspended and sometimes arrested, prompting groups like the NYCLU to call for a citywide discipline-code overhaul. At East Side, the purpose of the trainings and some of the Ferguson lessons was to prepare students for the high-stakes situations they could face outside of class.

“As a school,” Federman said, “it’s our responsibility to educate young people about the world and about life.”

The faculty came up with the idea for the Ferguson unit this summer while on a staff retreat around the time of the shooting and the subsequent protests. When they kicked off the lessons, they found that many students had a vague awareness of the incident but knew few details or had picked up misinformation on social media.

The students watched videos and read articles about the shooting of 18-year-old Michael Brown, which they related to other instances where police officers killed teenagers of color. They compared photos of the Ferguson protests to ones from the Civil Rights era, and analyzed how today’s media portrays people from different groups.

“For white males, they’ll show how they had bright futures ahead of them and what they did were just small, minor errors,” said Melissa Lopez-Garcia, 15. “Whereas for blacks, they just show the mistakes they made. ‘Oh, here’s this guys smoking a cigarette, he must be really bad.’”

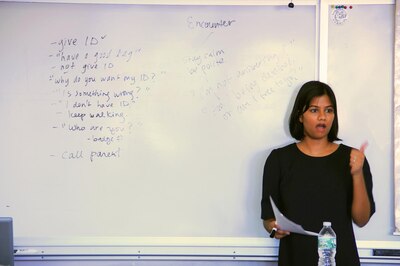

During 45-minute presentations Tuesday in different rooms throughout the school, eight NYCLU trainers explained to students their rights and responsibilities during encounters with police. The students also learned that officers disproportionately stop people of color.

That came as no surprise to 12th-grader Anthony Verdesoto, who said police have stopped him “many times” — in the train station, down the street from school, with his mother. He said it’s not a matter of what he does, but rather, who he is.

“Look at me,” said Verdesoto, 17, who is tall with long black hair. “I guess I can say I look sketch, but I’m not. They just base me on what I look like and who I could possibly be.”

The trainings, which will continue Thursday, are not an academic exercise.

At a school where most students are black or Hispanic — the groups that police stopped 85 percent of the time last year — students must be ready to interact calmly and safely with police officers, school staffers said. In fact, one student was arrested on his way to school on the first day this year because he entered the subway without a MetroCard, according to Federman, who has also invited police officers to talk to the students. Students and trainers said stops are still common, even as the total number of stop-and-frisks has recently plummeted.

Meanwhile, students who are less likely to be stopped were encouraged to record police stops they witness from a safe distance and to report misconduct. Or, in the parlance of the history curriculum the school uses, to be “upstanders” rather than bystanders.

“Their sphere of obligation,” explained digital-art teacher Leigh Klonsky, “is wider than themselves.”